Social Welfare and the Politics of Race in the Post-Civil War South

The policing of Black bodies has become an increasingly visible part of the American landscape, shining light on centuries-long violent policing of African Americans by whites as historians, including Kate Masur have shown. Recent reactions of the political right—outspoken criticism and fear of Black Lives Matters and rejection of Critical Race Theory—underscores an open and continued commitment to the policing of Black bodies and social constructs surrounding race. Rejection of the existence of systemic racism and rhetorical reinforcement of racial stereotypes continues the long history of the systematic policing of Black bodies that dates back generations (as historians, including, Kevin Kruse, Brian J. Purnell, and Annelise Oreleck note).

Political and cultural attacks on the welfare state over the last seventy years have played a central role in repackaging violent white resistance to Civil Rights into more palatable championing of “individualism” and rejection of the welfare state—rhetorical policing of the Black body that has become an accepted part of contemporary political rhetoric. Continuing a century-long battle by whites against federal government “meddling” in “Southern affairs,” Southern Dixiecrats embraced Barry Goldwater, who believed that “welfare programs cannot help but promote the idea that the government owes the benefits it confers on the individual, and that the individual is entitled, by right, to receive them.” Republicans championed individualism as fundamental to the health of democracy, demonizing “socialist” welfare programs and those reliant upon them.

The rejection of the welfare state by the New Deal generation, though ironic, repackaged racism in euphemistic language legitimizing the policing of the social constructs through use of stereotypes and hyperbolae to demonize Black communities. Most notable was Ronald Reagan’s “Welfare Queen,” which connected federal welfare and race through provocative imagery of fraudulent Black women. Successfully uniting Dixiecrats and conservative Republicans during the 1970s (as historians Lisa McGirr and Heather Cox Richardson highlight), the roots of this racialized and misogynistic link between race and welfare emerged first during the Reconstruction Era.

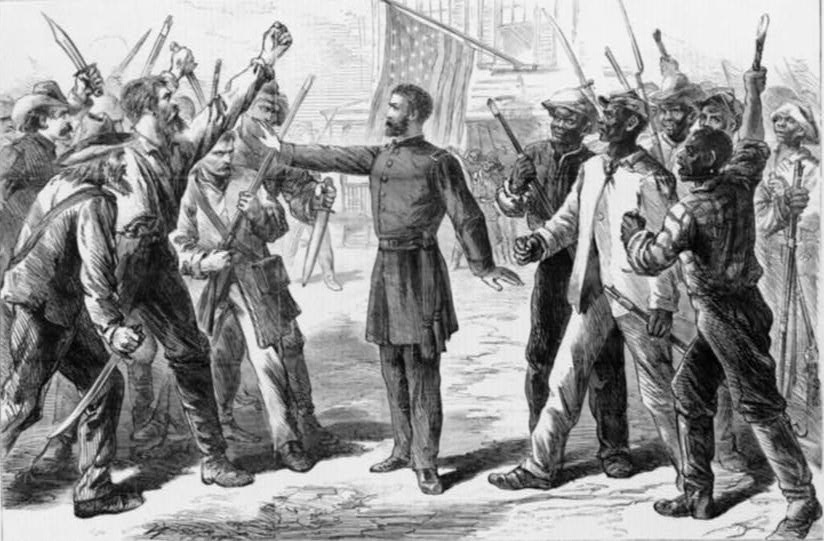

In the wake of the Civil War, the federal government sought to support freed people by establishing social welfare programs such as the Freedmen’s Bureau. Southern whites rejected these efforts in rhetoric, linking race and welfare that defines political discourse to this day. “The same sun is still there, the same mighty country is there: yes, and the same negro is there to work that once was,” editors of Louisville’s The Courier Journal lamented on June 14 1868. “But he doesn’t work, and why? Because while all the national wealth that once was there is there still, the Freedmen’s Bureau has gone there too . . . [and] tells the negro ‘Work no more, for in the sweat of the white man’s face at the north you may earn your bread.” These words echoed across the South and over subsequent decades.

This response reflected deeply rooted racial stereotypes that defined both political, social, and economic landscapes, North and South, in the nineteenth-century, as historian Stephen Kantrowitz notes. Post-Civil War conversations surrounding social welfare were ultimately undercut by policy that transcended sectionalism and wove racial stereotypes into the very fabric of progressive ideologies. While the federal Pension Bureau emerged as the primary mechanism of federal welfare, as historian Holly A. Pinheiro, Jr. details, conversations surrounding charity on the home front were racially divided. Though few questioned the extension of welfare to white veterans, widows, and orphans, there was mixed support surrounding charity for freed people.

The broader goal of the Freedmen’s Relief Association and other charities aimed at supporting freed people was simple and radical: an eloquent vision that “we [the nation],” noted Virginia Governor F.H. Pierpont, “shall be held accountable as a nation. The care of these four millions of human beings, thus thrown, uneducated and unprepared, upon their own resources, will require an immense amount of intelligent, considerate, and disinterested labor.” But critics bemoaned the focus on freedmen: “We must not,” wrote Henry Bellows, chairman of the Sanitary Commission, “permit the freedmen, or the needy Southerners, to absorb our attention to the neglect of this most deserving class of our own people—the widows and orphans of the war.” Bellows, who had called for Black enlistments as a means of filling New York’s quotas in 1863 and who fought for the welfare of soldiers and civilians, was unwilling to extend that sentiment to southern Blacks. The duality of these sentiments underscores the tepid empathy of a fragmented north that paved the way for the racialization of welfare politics.

Civil War Era welfare efforts were highly regulated, reflecting a political culture uncomfortable with the transformation of the role of the federal government in the daily lives of Americans. Consequently, Pension Bureau agents thoroughly vetted applicants and ensure only deserving poor received pensions. Although, as Noralee Frankel and Donald Shaffer highlight, pensions were available to all Union soldiers and families, Black men and women often had difficult producing evidence to support their claims, creating system accessible primarily to whites. The intense scrutiny of pension applications left a rich archive of Black life and the agency of freedmen and women during and after slavery which were used, at the time, to deny pension applications while perpetuate racial stereotypes that impact perceptions of black communities to this day.

One of the primary obstacles that some Black pensioners faced was that their marriages, while enslaved, were not considered legal and they struggled to provide reliable evidence of consent to marry or proof that they had lived as man and wife, as historian Brandi C. Brimmer reveals. In 1899, for example, pension agent Edward Elliot forwarded a report to Washington D.C. recommending that the pension of Amanda Arwine be revoked. Amanda’s marriage, in 1857, to Alfred Alwine, an enslaved man on a neighboring plantation, finally granted in 1869 after numerous individuals, white and Black, attested to the marriage. Thirty years later, however, Amanda, who had acquired by then a small two-room cabin and six acres of property, became the target of her former enslaver and overseer who claimed her marriage and subsequent pension application were fraudulent. Elliot sided with these two white men, claiming that “there has been no reliable evidence [there was, in fact, from numerous Black affiants] filed in lieu thereof to show that you and the soldier were joined in marriage by some ceremony deemed [legitimate] . . . In the absence of such proof you have no title to recognition as the legal wife of the above-named soldier and the allowance to you of pensions as his widow was erroneous and contrary to law.”1

Further influencing this, and other decisions, was a hyperfocus on social norms surrounding gendered behavior. Highlighting the complexity of slavery, affidavits in support of Black pensioners often related experiences that appeared to contrast with white-normative behavior of the time. Amanda, in her application, stated that she was the mother of twelve children, four born before she married Alfred. “I was not,” she noted “married to any of these men but stayed with them just as slaves did in those days.” After her husband’s death, she bore six more children with three different men. The exhaustive research done on Amanda by white pension agents suggests that it was they, not her, who took issue with this as it pertained to her pension claim. Similarly, pension agents investigating the claim of Sarah Smith in the wake of the death of her second husband, scrutinized the widow’s character. “The point with such widows that bears close watching,” noted Special Examiner A.F. Pasey in an overtly sexualized tone, “is this ‘take up’ adultery business. I don’t believe this woman guilty of violating the act of Aug 7 1882 [which terminated a pension based on ‘open and notorious adulterous cohabitation’] . . .She is,” he noted, “a handsome woman of the class above ‘take up,’” the agent noted. And, he commented, it was unlikely that she had taken up with a white man—as many others had—which he deduced from the fact that she had no baby—a tell-tale sign she was cohabitating and abusing the pension system.2

In this moment, these, and other Black women, who had long borne the brunt of chattel slavery, became the first of a long line of demonized “Welfare Queens” with the very programs designed to lift them up ultimately service as a means of the continued policing of their bodies and criticism of their experiences. Despite the systemic barriers that have long served to undermine and regulate access of Black communities, within these files we find rich evidence of the growth of post-war Black communities and the dynamic ways in which Black men and women navigated a post-slavery world. Facing the venom of their former enslavers and the apathy of their northern liberators, these men and women pursued every opportunity open to them in a manner that dispels the myths and stereotypes of those so invested in the preservation of the race line in American society.

For me, this essay offers an even more devastating critique of modern public discourse, when considered in light of W.E.B. Du Bois’ “Black Reconstruction in America.” Du Bois emphasized that the “four millions of [newly freed] human beings”–as referred to by the Virginia governor Pierpont above–should have been counted as similar in such desperate times to five million, dirt poor and totally uneducated whites. Radical Republicans argued at the time that the only real long-term remedy would require focusing reconstruction efforts on all of these people. Northern industrialists, Southern plantation owners, and even European immigrants with aspirations for Western lands all had other ideas for their own prosperity, however, which eventually led to a system of racial hatred and violence instead of a postwar rebuilding or “reconstruction” of the nation. I did not become aware of this particular work of Du Bois until well into retirement, but it seems as if it should be part of the foundational public school curriculum because of the devastating insights that it provides into the source of what has come to feel like a “Tower of Babel” in modern public discourse. Your essay above adds the equally devastating and traditionally overlooked sexist component as well. I am tempted to just shake my head in disgust and despair at such profoundly tragic and thoroughly institutionalized self-righteous ignorance. I am looking forward instead to both reading your current work on “The Crisis of History in an Age of Anti-Intellectualism,” and also gaining a deeper appreciation for why I never really cared for the history I was taught in public school.