Slavery and the Family Tree

How do you make a family tree when you may not know your family history? Beyond the very real physical and emotional toll on enslaved individuals, slavery’s violence also lay in its determination to erase or prevent the creation of family histories. As Frederick Douglass asserted in his 1855 autobiography, “Genealogical trees do not flourish among slaves.” In other words, the constraints of slavery made assembling and representing family history, and one’s identity in relation to it, a near impossible task. And for free Black Americans after emancipation who sought a history upon which to build their own family trees, the typical documentary evidence was often sparse.

The Black family has been a source of scholarly debate for decades, particularly after the 1965 publication of the Moynihan Report, a federal document that rooted the contemporary problems of Black Americans in slavery’s destruction of the Black family. In part to disprove this thesis, much of the scholarship on Black families since the 1970s has focused on the formation and composition of family during slavery, specifically whether enslaved individuals understood themselves as part of a community or kinship network rather than nuclear families.1 But beyond the actual makeup of the family was the imagined composition, including how individuals imagined their family’s past. Enslaved Americans looked not only to the future but also to the past as they struggled for freedom. And once that freedom came, Black Americans would seek to rebuild their families in the present in part by rebuilding their families’ histories.2 Writing a family’s history (including names and vital dates) was a common practice in nineteenth-century America, but was especially important for formerly enslaved peoples.3 Long denied the right to keep one’s family intact, newly freed peoples regarded genealogical records as documentation of their great strength in overcoming extreme obstacles.

Douglass’s assertion, then, was not completely accurate. Even with widespread familial disruption, illiteracy, and limited time, resources, and documentary evidence, enslaved Americans did have family histories. But they wanted more than to just know the histories; they wanted to showcase them for all to see. So enslaved individuals, and later their descendants, created material representations of those histories, their own kind of family trees. These might not have taken the shape of actual trees, like the ones so many of us create in grade school. In one remarkable case, though, a formerly enslaved man made his own kind of family tree out of wood. As the man’s daughter, Cornelia Winfield, described in 1937, “All the planks eny of our family was laid out on, my father kep’. When he came to Augusta he brought all these planks and made this here wardrobe.”4

Cornelia’s father, who had supervised the plantation workshop during slavery, managed to store pieces of wood that his family members were “laid out on.” This phrase could have two meanings: either they were beaten with these planks or lay upon them in death. Either way, this wood had been seeped in his family’s blood, tears, and bodily fluids extracted through the violence and death that accompanied slavery. It was with this wood, containing literal fragments of multiple generations, that Cornelia’s father made a wardrobe.

He was, according to Cornelia, a man devoted to his owner’s family, who stayed on the plantation in Oglethorpe County, Georgia, even after freedom. This would be the kind of thing white southerners used as evidence that the enslaved were as much a part of the “family” as the white members. Yet this wardrobe tells another, more nuanced, story. He did not make a wardrobe from the planks upon which his enslavers lay, nor simply accept as a gift one of their discarded wardrobes. This would have represented their family history, not his own. Cornelia’s father retained wood with the essence of his family history to make the wardrobe, one that represented the hardships of slavery and the possibilities of freedom. This family tree did not ignore or underplay the difficult past of so many Black families.

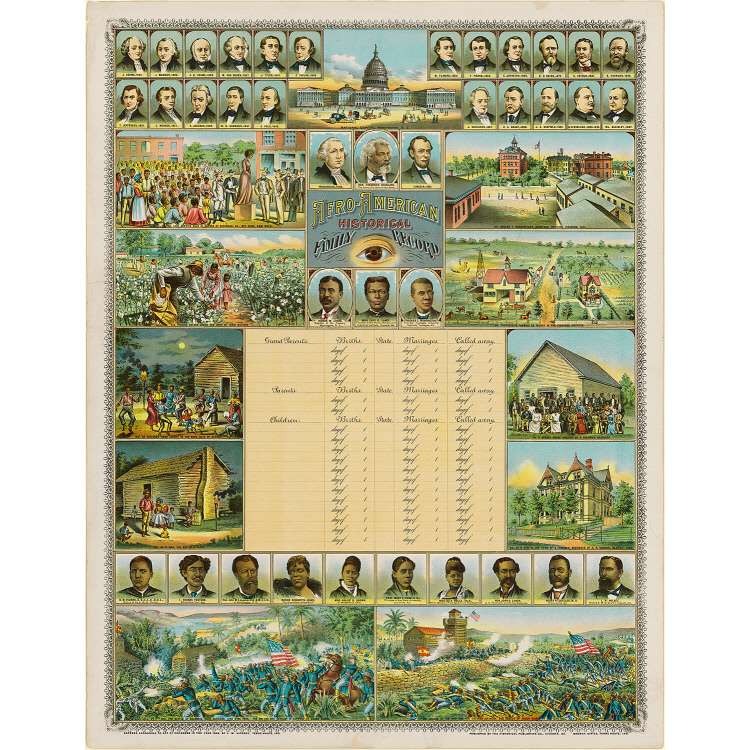

Similarly, other kinds of family trees make clear the family’s role in bridging slavery and freedom. An illustrated family tree, like the 1899 Afro-American Historical Family Record, visually demonstrated the belief that family (represented by the interior space that would include important family names and dates) spanned the transition from slavery (represented through images on the left) to freedom (images on the right). Chromolithographs like this one would have been framed and hung in prominent places in the home, such as parlors, as a means of displaying to visitors one’s family history, their pride in that history, and that family’s connection to a broader American history. Not only were famous people recorded in the Afro-American Historical Family Record, like Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and Ida B. Wells, but also iconic white Americans associated with freedom, including George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. These family trees indicate that many Black Americans believed their family’s past enslavement built their present state of freedom. Just like the elite white families who claimed ancestral ties to the Mayflower or American Revolution, Black Americans claimed their ties to slavery as an emblem of their Americanness.

Interestingly, the Afro-American Historical Family Record was produced in Augusta, Georgia, where Cornelia Winfield lived. Perhaps Cornelia’s home included one of these illustrated family trees; perhaps not. What we do know is that her family wardrobe was the emblem of family history she happily discussed with visitors. One recorded instance is when she interviewed with Works Progress Administration’s Margaret Johnson. This family tree of sorts sat in Cornelia’s sitting room. Born into slavery, Cornelia lived just south of the Laney-Walker District, a segregated neighborhood in Augusta, Georgia, when she spoke with Margaret in 1937. Margaret was one of the many Works Progress Administration workers in the late 1930s who traveled the South recording the stories of formerly enslaved individuals like Cornelia. These sources are notorious among scholars of African American history, derided in many cases as untrustworthy memories of elderly folks or suspicious answers wrested by mostly white (and thus prejudiced) interviewers.5 Indeed, it is hard to verify much of the information. The wardrobe itself is likely lost to time; not even a photograph of it exists for us to study. We do not know the style, the materials, the creation date, or many specifics about it. We only have what Cornelia told Margaret Johnson, and then what Margaret felt compelled to record for posterity.

But the story of Cornelia’s wardrobe indicates that there is still much to learn from even difficult sources like WPA narratives. Scholars of material culture know that we (unfortunately) cannot always get our hands on the stuff we study. So we dig into the text to find the material and, perhaps more importantly, the meaning of it. The details Cornelia chose to relate about the wardrobe do not tell us much about its composition, but they do tell us everything that was important to her about its composition. Cornelia described how the wardrobe survived a conflagration that consumed her entire home: “When the fire burnt me out, this here wardrobe was the only thing in my house that was saved.”6 The strength of her enslaved ancestors whose bodies touched the wood seemed to seep into the wood itself, imbuing the wardrobe with an almost immortal quality. Like the enslaved individuals who touched the wood, this wardrobe resisted the oppressive conditions that sought to destroy it. Her desire to tell the story of this wardrobe indicates her pride in this object, her love of it, and what it represents. Like her father before her, it represented her family history. It represented Black history: a history that could have been swept away by slavery but was retained for posterity. Her family history was embedded in an object. Her family tree was not a tree at all; it was a wardrobe.

- The scholarship on the black family is vast and spans the Atlantic World, but in the United States extends from many of the studies of the 1970s, including Herbert Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976); and John Blassingame, Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979). ↩

- For more on how formerly enslaved individuals sought to rebuild their families, see Heather Andrea Williams, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery(Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012). ↩

- Lauren F. Winner, A Cheerful and Comfortable Faith: Anglican Religious Practice in the Elite Households of Eighteenth-Century Virginia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 168. ↩

- Cornelia Winfield, WPA Slave Narrative Project, Georgia Narratives, vol 4, pt 4, Federal Writer’s Project, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, 178. ↩

- For a succinct and useful overview of the debate over the veracity and usefulness of WPA narratives, see Jeff Strickland, “Teaching the History of Slavery in the United States with Interviews: Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–1938,” Journal of American Ethnic History33, no. 4 (Summer 2014): 42–43. ↩

- Winfield, WPA Slave Narrative Project, 178. ↩