Slavery and Disability in Antebellum America

In 1794, U.S. inventor Eli Whitney patented a new type of cotton gin that could remove seeds from short staple cotton, the transformative crop that enslaved workers would plant across the Southern Blackbelt. This invention has often been characterized as a critical turning point in the history of U.S. slavery, when suddenly the institution went from seemingly dying to thriving, almost overnight.

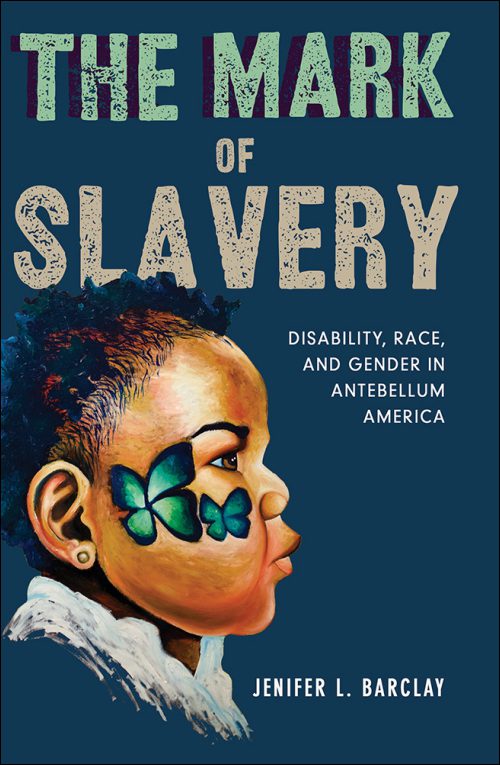

This was only a part of that history. The gin and other features of antebellum slavery would influence how disability was understood in the United States, as revealed in Jennifer Barclay’s new book The Mark of Slavery: Disability, Race, and Gender in Antebellum America. In terms of the cotton gin, it became feared on plantations as one of the more dangerous machines, known for its ability to literally shred the limbs of enslaved people. More critically, the cotton boom helped slavery expand and caused the racially-charged debate over abolition to protract well into the nineteenth century. As Barclay argues, during this decades-long debate over slavery, pro- and anti-slavery commentors used racial arguments about disability for and against the institution’s persistence.

Whether it be in the law, medicine, politics, or entertainment (subjects Barclay analyzes in different chapters), ideas of race, disability, and gender became fused together by antebellum commenters. Deployed by such a diverse range of institutional and social actors, racialized notions of disability were suffused throughout American culture and politics. Yet, the Mark of Slavery is not simply a study of disability discourse. Rather, the book examines disability as both a discourse about race and slavery and as a lived experience affecting the lives of thousands of enslaved people.

While often glossed over or ignored in histories of slavery, disabling conditions proliferated among enslaved people. “Anywhere from 360,000 to 540,000 of the 4 to 6 million people in bondage on the eve of emancipation experienced missing or misshapen limbs, deafness, blindness, congenital anomalies, epilepsy, insanity, debilitating diseases, and a host of other apparent and nonapparent conditions,” Barclay explains (16). Anything from losing an appendage in a cotton gin to arthritis represented conditions that enslaved people might endure. Harriet Tubman, for example, suffered from epilepsy. For a few minutes mid conversation, she could abruptly “ease talking, slump over, and later just as abruptly resume the conversation where she had left off” (35).

These conditions also affected family life in complex ways, the subject of chapter two. For family life within the precarity of the plantation system, disability was a double-edged sword. On the one hand, enslaved people with disabilities were monetarily devalued in a system that almost exclusively prized labor capacity. Thus, while for many enslaved people the fear of being sold was persistent and ominous, those with disabilities could dread being sold less. Enslavers saw fewer profits from their sale, and less demand existed. In this sense, disability could provide social stability. On the other hand, disability wrought social stigma within enslaved communities. “Because of stigma attached to some disabilities throughout the nineteenth century,” Barclay explains, “some nondisabled, enslaved people refused to marry or form lasting relationships with those identified as disabled” (60).

Slavery and southern physicians also inhibited the development of the social state in the South. Tapping into the racial science popular among Atlantic physicians, southern doctors argued that slavery was essential to managing a racially inferior population of African descent. Likewise, racial beliefs about the local climate lent weight to the notion that Black people toiling on plantations was inherently healthy. These arguments about the health of slavery coupled with a paternalist notion that enslavers cared for enslaved people’s wants and needs allowed southerners to demure on investing in the social state. As Barclay asserts, “southerners argued that the institution of slavery mitigated local and state governments’ need to establish significant social welfare systems for the indigent and disabled” (73).

While done to depict slavery as morally wrong, anti-slavery thinkers also used disability to discuss enslaved people, further linking together blackness and disability. Some abolitionists described enslavement as leprous and enslaved people as poor deluded creatures. Sentiment for the “disabled slave” likely led some whites to change their views of slavery, but also helped solidify stereotypes of Black people as degraded. By linking blackness and disability, abolitionists revealed the limits of the movement. As Barclay describes, “they ultimately failed to recognize the mutually constitutive relationship between racism and ableism that upheld the social hierarchies responsible for maintaining the status quo” (107). In short, while abolitionists undoubtedly meant to critique the brutality of the slave system as unjust and harming Black people, they also aided in depicting Black people as inherently disabled and othered. While pro- and anti-slavery commenters’ aims were radically different, both sides of this debate helped produce stereotypes about race and ability with enduring consequences.

Politics was only one part of an American culture producing racial stereotypes centered around ability. Specifically, minstrel shows rested their stereotypes on both ableist and racist discourse. In the case of the blackface character Andrew Jackson “Dummy” Allen, the central conceit of the character was his deafness and the supposed humor that emanated from it. According to Edwin Forrest, the actor portraying Allen, “Allen was very deaf and consequently very annoying to those with whom he played who not unfrequently took an unkind revenge on his misfortune” (138). Thus, audience members would watch as other characters feigned speech to confuse Allen and played tricks on the man. The theater was effective entertainment, Forrest explained, as “the audience roared with laughter” at the enslaved character Allen’s expense (139). In short, minstrelsy made literal what was more implied elsewhere that Black people were inherently disabled, and Black and “freak” were virtually synonymous

Utilizing a range of archival and print sources, The Mark of Slavery makes plain how ideas of ability and racism co-evolved during this period. Most impressive, Barclay captures a wide range of cultural institutions and factions in American life that traded in ableist stereotypes of blackness. In politics, medicine, and entertainment, Black people were depicted as inherently disabled in body and mind. While these stereotypes could be deployed for abolitionist or pro-slavery ends, they had a shared effect of tying disability to blackness and vice versa.

Also important is how Barclay examines disability as a material condition affecting people’s daily life and social possibilities. At times, disability history, which focuses on challenging and life-influencing conditions, can examine discourse at the expense of the histories of everyday people. Barclay though effectively navigates both disability as a constructed category and as a stand in term to describe diverse life-shaping conditions.

Finally, in grappling with both abolitionist and pro-slavery discourse, Barclay illustrates how slavery and the racial system it produced affected American culture across the Mason-Dixon Line. Thus, racism and ableism were national in nature. In sum, the second slavery caused the spread of slavery and the maiming of countless more bodies, but it also ensured that American politics at its point of inception was shaped by a profoundly racist, sexist, and ableist culture.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.