Slavery and America’s Legacy of Family Separation

In early May 2018 news broke that federal officials had lost track of nearly 1,500 children. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that officials would separate undocumented families. Characterizing immigrant parents as smugglers of their own children, Sessions warned that families who wanted to remain together should not attempt to enter the United States. And then came reports that federal officials had “misplaced” roughly 1,500 immigrant children. Older reports of children being placed with traffickers and four-year-old reports of the migrant crisis recirculated. Both added to the confusion and outrage of many on social media. And fairly quickly, social media conflated two populations of children: migrant children who arrived at the border seeking asylum and immigrant children who officials separated from their parents during raids on their communities and border confrontations. Before long, reports aimed at parsing out what exactly was going on appeared in major news outlets. “Is this America?” many asked.

The story continues to develop rapidly. After public outrage and activism put pressure on elected officials and the Trump administration, the President signed an executive order ending his administration’s policy of child separation. But the new policy incarcerates families indefinitely and offers no solution or plan for reunited families already separated by the administration’s previous policy. Additionally, reports of abuse in facilities that house immigrant children and reports that some of the almost two thousand children taken from their parents are now in the custody of foster care and adoption agencies that have contracts with the federal government raise additional concerns about the administration’s intent to reunite children with their families. The administration announced a plan to reunify children with their parents on June 24, 2018. But this announcement was short on details and provided little clarity.

The histories embedded in my experience and my scholarship—as a descendant of immigrants and a scholar of American slavery—collide in every headline. The prejudice that each side of my family endured were similar to the fear, misunderstanding, and racism that today’s immigrants encounter. But more pointedly, I know very well that forced family separation was always a fixture of the lives of enslaved people. Enslaved children, after all, were a lucrative business.

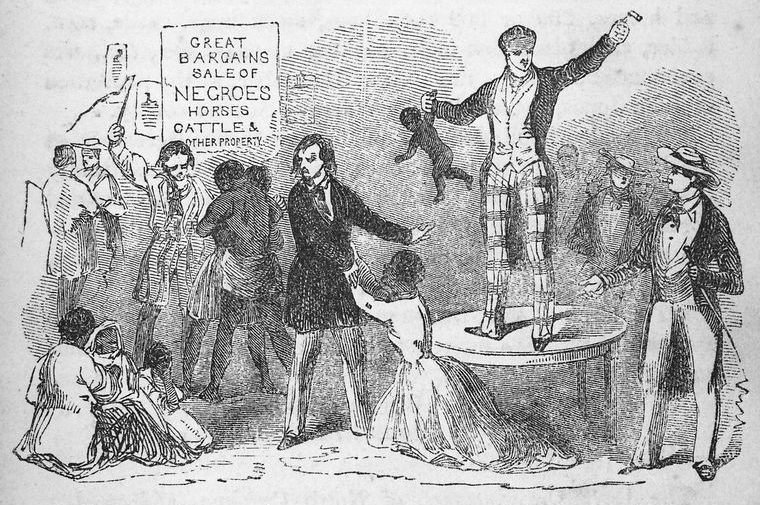

This was certainly the case in the city of Lexington, Kentucky, the site of one of the most important slave markets in the state. The market, like others across the nation, was a terrifying place for enslaved children who performed necessary labor even while young. The expansion, maintenance, and future of slavery as an economic system depended on these children, particularly after the close of the American trans-Atlantic trade in 1808. Former slaves from Lexington, Kentucky, who were enslaved as children testified to their fear, pain, and horror in WPA Narratives, interviews conducted during the Great Depression. These children, even from a young age, were well aware that their sale could occur at any moment.

Harriet Mason remembered her mistress forcing her to leave her home and family in Bryantsville, Kentucky, to work in Lexington as a servant at the age of seven. She remembered, “when we got to Lexington I tried to run off and go back to Bryantsville to see my [mother].” The grief of a childhood spent away from her family at the whim of her owner led her to suicidal thoughts, “I used to say I wish I’d died when I was little.” Even in her old age she was firm that, “I never liked to go to Lexington since.”

Her recollections capture the cruelty of family separation and underscore how children were big business in the history of slavery. They were laborers and valuable property. They could be hired out just like Harriet Mason. Slaveholders borrowed against their human property. They gifted enslaved children to their white sons and daughters as children, upon their marriages, or as they struck out to begin their slaveholding legacy. And of course, slave children could be sold down the road and down the river. Children knew that at any moment this could happen to them. For example, George Scruggs, an ex-slave whose owner hired him out as a child to work in Lexington, remembered his fear when seeing a slave coffle, “The colored folks were walking, going down town to be sold. When I first saw them coming I got scared and started to run.”

To profit from slavery and participate in slaveholding, Lexington’s white residents did not even need to own, buy, or sell a single slave. Someone made the shackles. Someone ran slave jails. Someone generated the official documents needed to transfer property. Someone hired enslaved children to work in their homes and businesses. Adults running with children from officials who would separate them was a feature of fugitivity during American slavery. To produce the “fugitive” category, a range of institutions sprang up. Local money paid sheriffs, courts, and officials to uphold the law that protected slaveholders’ rights to their human property. Someone printed runaway ads. Someone made money on enslaved peoples’ bodies at every juncture.

Today, children’s labor remains valuable. One concern with how officials treat immigrant children taken from their parents is that some children released from custody were given over not to relatives or appropriate guardians, but traffickers. Human trafficking is not unknown in the United States. Concerns over child labor have long gone hand in hand with concerns about the abuses suffered by undocumented families.

Along with physical labor, children deemed by the state to have unfit parents and placed into adoptive homes, perform emotional labor. Adoptees not only lose their birth families in the process, but they also lose ties to culture, language, country, history, and identity, and must contend with societal expectations that they be grateful for a “better life” in the face of it all. Children of color adopted by white parents also face racism in their new homes and communities. There is emotional labor too in being the physical body that allows white families to appear more liberal or multicultural, even if the opposite is true. In the United States, adoption is an industry and, as adoptee advocates continue to warn, it is poised to profit from family separation. There is already precedent for keeping children in the United States after a parent has been deported and awarding custody to American adoptive parents over immigrant parents caught up in immigration proceedings or because they were detained or incarcerated.

The money does not stop with the potential profit in children’s physical and emotional labor. Similar to the many industries, individuals, and laws needed to perpetuate American slavery, imprisoning immigrants is also big business. Reports confirm that housing children separated from their parents costs nearly $800 per child per night. The Trump administration began awarding contracts and grants to companies, non-profits, and businesses shortly before announcing its zero-tolerance family separation policy. Officials house women and minor children in separate facilities from adult men and adult children. This requires additional facilities and encourages the separation of families in custody. Companies that made massive profits from mass incarceration began pivoting towards immigrant incarceration before President Trump took office. Once in office, the President’s policies ushered in a boom for industries that build, maintain, and supply prisons. While the crisis involving children continues, ICE raids ensure that the population of immigrants in federal facilities will rise.

African Americans confront these realities daily: Black families are separated by the bond and bail system, incarceration, the child welfare system, and the criminalization of poverty. All can lead to family separation and the loss of one’s children. Child welfare advocates also recognize the link between the disproportionate number of Black children in the foster care system and the pipeline from foster care to prison. All of these contemporary systems of power are echoes of legal and social structures that devalued enslaved parents and profited from enslaved children during American slavery.

We need to acknowledge these links to the history of American slavery and the ways that African Americans continue to endure state. Histories of children in slavery have much to teach us. Children then as now have their own experiences, ones to which we should attend with care. After all, there is potential harm embedded in every catchy #wherearethechildren hashtag. Some of the children are with their family and other undocumented kin. Finding the children would mean exposing networks that communities build and maintain to evade officials and keep their families together.

Following the money also exposes the truth in another adage: money talks. Already, companies connected intentionally or unintentionally to the crisis have responded to consumer pressure by divesting. The rising number of angry calls to local officials who face reelection also put pressure on lawmakers. State governors are refusing the federal government’s call for National Guard units at the border. Some local officials are refusing to help federal agents. Atlanta’s mayor has refused to accept new ICE detainees in Atlanta jails. The flood of donations to groups organized by and for immigrants are another way for money to speak. Solidarity with and support for those who have long done the work of supporting immigrant communities can be powerful in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

In a middle school project I had students read ads place by family members seeking knowledge on lost family members. My students concluded that reuniting family members and legalizing marriages were the main goals for freed blacks during Reconstruction.

And extremely difficult it was too, as people may have changed names once freed.