Silence and the Inner Lives of Black Nationalist Women

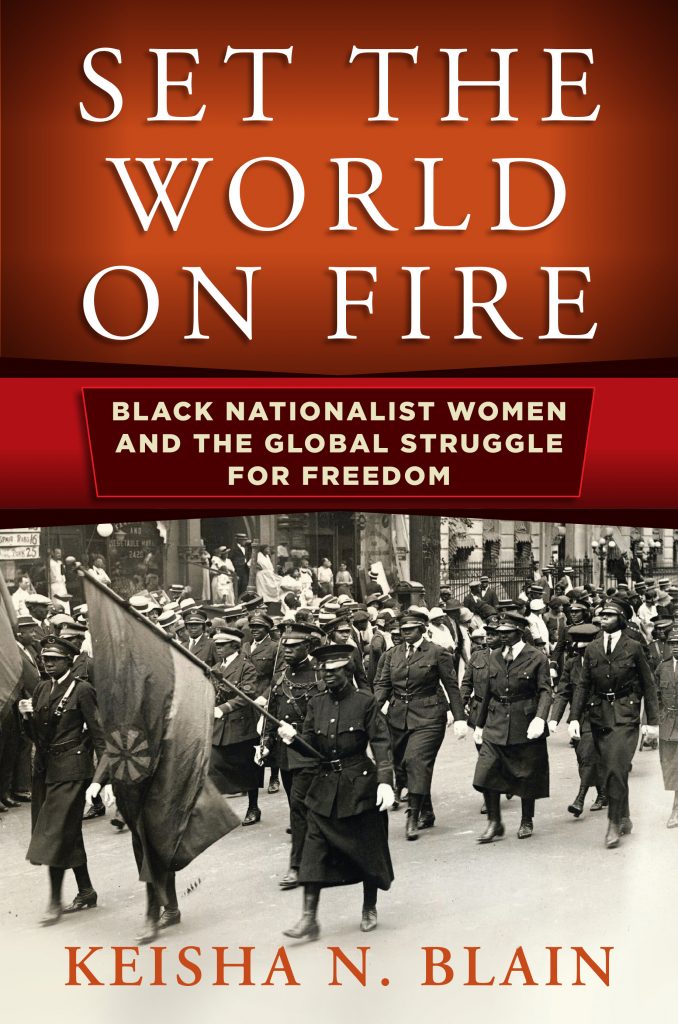

*This post is part of our online roundtable on Keisha N. Blain’s Set the World on Fire

Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, Celia Jane Allen, Ethel Collins—few people have heard of these Black women who “set the world on fire.” That will change thanks to Keisha N. Blain. Unearthing and mining neglected sources, Blain’s Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom offers a clear, textured, and compelling analysis that illuminates how these Black women became the intellectual architects and organizational doyennes of an overlooked period of Black nationalist ferment during the Great Depression, World War II, and the early Cold War.

Set the World on Fire begins with Black women in the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), a critical organization and generative space for Black nationalists. Blain doesn’t stay on that familiar and well-trod terrain too long but shifts focus to Gordon, Allen, and other little-known Black women who seized the opportunity to “refine and redefine black nationalist politics on their own terms” in the “post-Garvey moment” (3). Born to working class families in the Jim Crow Deep South, Gordon and Allen both moved to Chicago during the first wave of the Great Migration. Faced with resistance to female leadership in the UNIA and ideological differences with a would-be male collaborator from the Philippines, Gordon established the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME), an organization that “provided a crucial space for working-poor black men and women in Chicago to engage in black nationalist and internationalist politics during the economic crisis of the 1930s” (61). From 1936 to 1942, Allen, as its principal organizer in the Deep South, not only expanded the PME’s membership but also indispensably kept “black nationalist ideas alive in the U.S. South.” As Blain shows, Allen braved the ever-present dangers of racist and sexist violence to gain an estimated 400,000 signatures from Black southerners in support of the PME and its emigrationist agenda (103).

By mining previously neglected private letters, U.S. government records, Black newspapers, and unpublished songs and poetry, Blain does a remarkable job of recovering the ideas and activism of PME leaders and their contemporaries including Amy Jacques Garvey, Maymie De Mena, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. In particular, Set the World on Fire captures the charisma, intellectual dynamism, and clever self-presentation that allowed Gordon to win the support of fellow Black activists, influential white politicians, and working class Black people alike. The latter included Juanita Carter, a young PME member who composed an ode to Gordon set to the tune of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” in order to celebrate the impending day when “Mother Gordon will lead us home” (130).

Clearly evoking endearment and profound respect, the term “Mother” also might provide readers with a glimpse into how Gordon presented herself as a respectable matriarch. Indeed, the public images cultivated by Black nationalist women who asserted their racial leadership were often strategically deployed “in a way that would not appear threatening to male members of the community” (85). And, just maybe, these public images, which were crafted to promote and advance their Black nationalist politics, were also meant to protect their privacy as well as shield their complex, agonizing, and maybe even tragic inner lives.

Set the World on Fire consistently encourages these considerations. While focused on the intellectual and political work of Black liberation, making great sacrifices to challenge global white supremacy, Blain’s Black nationalist women, as whole human beings, not only navigated a Black nationalist world shaped by multiple racial ideologies and political goals but also by gendered imaginings, expectations, and frustrations. Their activist biographies and intellectual production are inseparable from their lived experiences conditioned by gender, class, and race.

At times, these connections reveal themselves in archival silences. As Blain notes, the circumstances of Gordon’s first marriage at the age of fourteen to a man more than thirty years older than her remain unclear as do the details about the fatal injuries that her son sustained during the East St. Louis race riot of 1917. Gordon perhaps chose not to disclose personal details related to Black sexuality, womanhood, and motherhood, protecting her private life in ways that Allen might have too. Born in Mississippi, the general date and location unknown, disappearing from surviving archival records around 1942, Allen “left no personal archives and few writings” (78). “Very little,” Blain concedes, “about Allen’s personal life is known” (79).

How should we interpret these silences? While acknowledging that most working class Black women also left behind few writings from which fuller biographies can be recovered, Blain suggests that Gordon might have chosen not to reveal personal and potentially intimate information about herself to confidants even when opportunities to do so presented themselves. In fact, while peers including Maymie De Mena created and re-created elaborate self-presentations for perhaps similar reasons, she appears to have left those “closest” to her in the dark. When Gordon died from heart failure in June 1961, her third and final husband could not provide her date or place of birth. No public announcement of her death appeared in the United States, not even from her fellow PME activists who ostensibly knew her best.

To be sure, there are undoubtedly numerous ways to interpret this evidence or lack thereof. What I am suggesting, however, is that Set the World on Fire calls us to make use of distinct and overlooked archives as Blain so carefully does and pay attention to when their silences speak, reveal trends, or open a series of potentialities. It is generative and powerful in large part because it encourages us to dig even deeper—to wonder, ponder, and raise more questions about the Black nationalist women who it rightfully moves from the margins to the center.

Here, Darlene Clark Hine’s foundational work in Black women’s history might help us make these silences legible and provide a guide for the kinds of questions we must continue to ask. In her classic article entitled “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West,” Hine argues that Black women developed “a culture of dissemblance” in response to the experience and threat of rape and sexual violence. She finds, too, the aspirations that motivated this “dissemblance . . . the behavior and attitudes of Black women that created the appearance of openness and disclosure but actually shielded the truth of their inner lives and selves from their oppressors.”1 In Hine’s estimation, a “secret, undisclosed persona allowed the individual Black woman to function . . . to found institutions” and, perhaps, movements including the PME. It allowed Black women to not only avoid negative stereotyping but also “accrue the psychic space and harness the resources needed to hold their own in the often one-sided and mismatched resistance struggle” against a racist, classist, and patriarchal world.

If the occasional self-induced obscurity of Blain’s protagonists encourages historians to pay renewed attention to the silences that abound in Black women’s history, then their use of and emphasis on migration reinforces it. Although Gordon relocated to Chicago after witnessing a massive lynch mob pass her childhood home in Louisiana and after surviving the East St. Louis race riot, it is possible that the endemic sexual violence against Black women in the United States also motivated her to join thousands of her peers and “quit the South” or even, as Blain’s rendering might suggest, attempt to quit the United States for West Africa. For instance, in a compelling and evocative scene in Set the World on Fire, Gordon stands before a group of white reporters after the failure of the Greater Liberia Act of 1939 that would have provided federal funding in support of her efforts to relocate African Americans from the United States to Liberia and proclaimed: “You people don’t want us and we don’t want you . . . All of you know . . . that in days gone by your male ancestors used to raise their white children in the front yard and their black children in the back yard” (127).

Gordon’s public condemnation of the sins that made the United States irredeemable to emigrationists and Blain’s capturing of that pivotal moment challenges scholars to continuously ponder how we can creatively, vigilantly, and carefully acknowledge the inner, private, and even unknowable lives of working-class Black women theoreticians. Accordingly, let me end with a few questions for further consideration. How, for instance, might we think about one PME member’s lamentation that she had “5 children [and] I don’t see any future for them here . . . I have always wanted to be free” (109) in light of Hine’s contention that the “most common . . . motive for running, fleeing, migrating was a desire to retain or claim some control and ownership of [Black women’s] own sexual beings and the children they bore?” What more can or should we make of UNIA member Josephine Moody’s resolution to “set the world on fire” for “freedom and justice and a chance to build for ourselves (137)? Might the politics of silence, if practiced by Black nationalist women, influence their dreams, expectations, and motivations?

In short, Blain’s pioneering book does not just belie the longstanding assumption that the period between the height of Garveyism and the rise of Black Power was “an era of declining black nationalist activism” (4). It also encourages even more scholarship on the gendered meanings and manifestations of Black nationalism.2 Born from the minds and experiences of Black women including those foregrounded by Blain, it is possible that Black nationalism, as some historians of gender and sexuality have suggested, needs to be understood as not simply or solely a politics of Black pride and Black economic and political self-determination but also as a tangible idea of and search for respect, sexual freedom, physical safety, and dignified work.

Along with Ashley D. Farmer, Michele Mitchell, Robyn C. Spencer, Ula Y. Taylor, Rhonda Y. Williams, and other Black women historians, Blain advances our understanding of Black nationalism by reframing its longstanding periodization, challenging its masculinist narratives, and foregrounding questions of gender and sexuality. She has offered us a paradigm-shifting history that makes the appeal, possibilities, and stakes of Black nationalist and internationalist politics more apparent and rich.

- Darlene Clark Hine, “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West,” Signs 14, no. 4. Common Grounds and Crossroads: Race, Ethnicity, and Class in Women’s Lives (Summer 1989), 912. For a critical evaluation of the “culture of dissemblance” in relation to a “tradition of testimony,” see Danielle L. McGuire, “‘It Was Like All of Us Had Been Raped’: Sexual Violence, Community Mobilization, and the African American Freedom Struggle,” The Journal of American History 91, no. 3 (December 2004): 906-931. ↩

- Foundational work on this topic includes E. Frances White, “Africa on My Mind: Gender, Counter Discourse and African-American Nationalism,” Journal of Women’s History 2 (1990) and Barbara Bair, “True Women, Real Men: Gender, Ideology, and Social Roles in the Garvey Movement,” in Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women’s History, ed. Dorothy O. Helly and Susan Reverby (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992): 154-166. ↩