Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: A New Book on Black Women in New York City

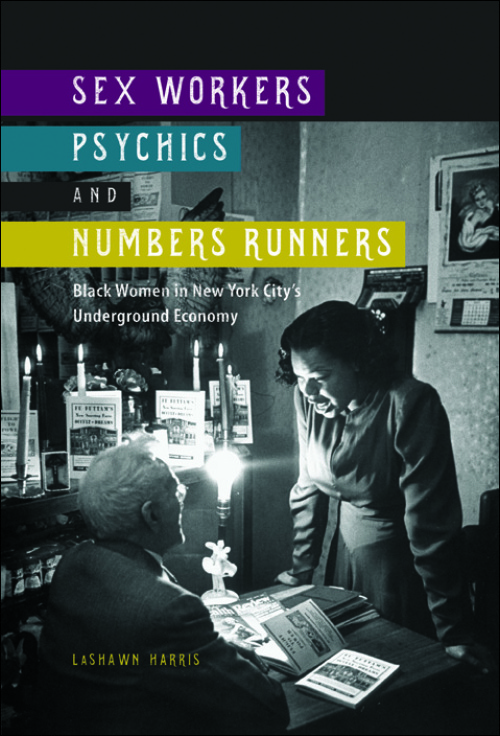

Today is the beginning of our online roundtable on LaShawn Harris’s new book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016). Dr. Harris is an Assistant Professor of History at Michigan State University. Completing her doctoral work at Howard University in 2007, her area of study focuses on twentieth century United States History. Harris has recently published articles in the Journal of African American History, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, and the Journal of Social History. Her first book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, examines the public and private lives of an all-too-often unacknowledged group of African American female working-class laborers in New York City during the first half of the twentieth century.

In this post, I offer a brief introduction to the text and author. Over the next few days, we will feature responses from Julie Gallagher, Shannon King, Talitha LeFlouria, and Brian Purnell. On the final day, LaShawn Harris will offer a response.

In her seminal essay, “Women in the Documents,” historian Ula Y. Taylor argues that black women’s representation in the archives is “limited, heavily tainted, or virtually non-existent,” underscoring the need for scholars to utilize creative and rigorous “historical methods and theoretical ideas.” This is certainly true. Those of us who study black women’s history can attest to the limitation of archival sources as well as the distortions present in the sources that are available. As a result, doing research is no easy task—not that it ever is. But, scholars in this field have to be especially attuned to the limitations, distortions, and omissions in archival sources and be willing to draw on a wide array of sources—and fields of study—to tell a rich and nuanced story about black women’s lives.

Once in a while, a scholar comes along with a special knack for not only uncovering an array of hidden sources but with an ability to read these sources in a way that brings black women’s narratives to life. LaShawn D. Harris is one such scholar. I first encountered Harris’s work as a first-year graduate student in 2009 while working on a paper on black women’s radical politics. It was her article, “Running with the Reds: African American Women and the Communist Party during the Great Depression,” published in the Journal of African American History. An excerpt of her dissertation, Harris’s article highlighted the ideas and activities of black women in the Communist Party—a topic which was at the time still fairly new. With the exception of Carole Boyce Davis’s groundbreaking study, Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones, only a few articles—and then dissertations—had been published on black women in the U.S. Communist Party (CPUSA).

Drawing on an array of sources, Harris told the story of how black women found in the CPUSA a space in which to challenge racism, imperialism, and sexism—even as they struggled to articulate a voice in the predominantly white and male organization. These points would be further expanded in the publications of three dynamic books on the topic: Dayo F. Gore’s Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War, Erik S. McDuffie’s Sojourning for Freedom: Women, American Communism and the Making of Black Left Feminism, and Gregg Andrews’s Thyra J. Edwards: Black Activist in the Global Freedom Struggle. But, it was through Harris’s JAAH article that I first began to understand how the CPUSA provided a crucial site for black women’s engagement in national and global politics.

Uncovering Harris’s JAAH article would lead me to many others. A prolific scholar, Harris has published at least five journal articles to date in some of the leading journals in the field —including an award-winning piece in the Journal of Social History. Each publication highlights her ability to not only craft a beautiful story but her ability to dig—and I do mean dig. Harris is the kind of scholar who librarians and archivists know well—the kind of persistent scholar who takes seriously what it means to truly research a topic. If a primary source exists, rest assured that Harris can and will find it.

As a graduate student, I found inspiration in Harris’s work—as I do now. Her close attention to detail, her ability to read “against the grain,” and her commitment to excavating the stories of black women “on the margins” drew me to her work. And not surprisingly, it also drew me to her as a person. After a chance encounter at a conference in 2013, we began corresponding frequently and grew to become close friends.

When she told me she was writing a new book on black women in New York City—and had decided not to turn her dissertation into a book—I was stunned. It seemed like such a risky move. I remember being worried for her and I probably asked her at least once if she wasn’t also worried about having to do research “from scratch.” Now that the book is published, I can’t help but laugh (at myself) for asking such a question not only because she pulled it off but she did it quite well. A quick survey of her footnotes unveils the story of the days—and nights—Harris spent combing through an array of materials in an effort to do what often seems impossible.

In LaShawn Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, the stories of black women in New York who have been absent in historical narratives come to life. Harris takes us on a journey of New York City unlike any we have ever seen and re-introduces us to Harlem through the eyes of fascinating black women like Madame Stephanie St. Clair and Dorothy “Madame Fu Futtam” Matthews.

In LaShawn Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, the stories of black women in New York who have been absent in historical narratives come to life. Harris takes us on a journey of New York City unlike any we have ever seen and re-introduces us to Harlem through the eyes of fascinating black women like Madame Stephanie St. Clair and Dorothy “Madame Fu Futtam” Matthews.

Telling the story of black women in New York City’s underground economy during the early twentieth century is no easy task. As I finish revising my own book, which attempts to center the ideas and activism of women who have been relegated to the footnotes of U.S. and global history (if they appear in the footnotes at all), I know full well that a book like Harris’s is an accomplishment of monumental proportions.

No book is perfect but the best books are the ones worth engaging—and even debating. Harris’s book deserves our time and our close attention. Over the next few days, I hope you will read the book along with us and share your insights, questions, and constructive feedback.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Excellent!!! I look forward to purchasing and reading this literary work.

This is so wonderful! I’ve always said that if I ever worked on a Ph.D. then it would be in history, with a focus on Africam American women in cities (I grew up in DC) from the late 1800s to 1940s. Thank you so much for writing this and all of the research that went into it.

I’ll be reading and smiling, surely.

I am looking forward to reading the book myself, thank you for a great intro!

I adore studying and I believe this website got some truly utilitarian stuff on it!