Searching for Anna Douglass in the Archives

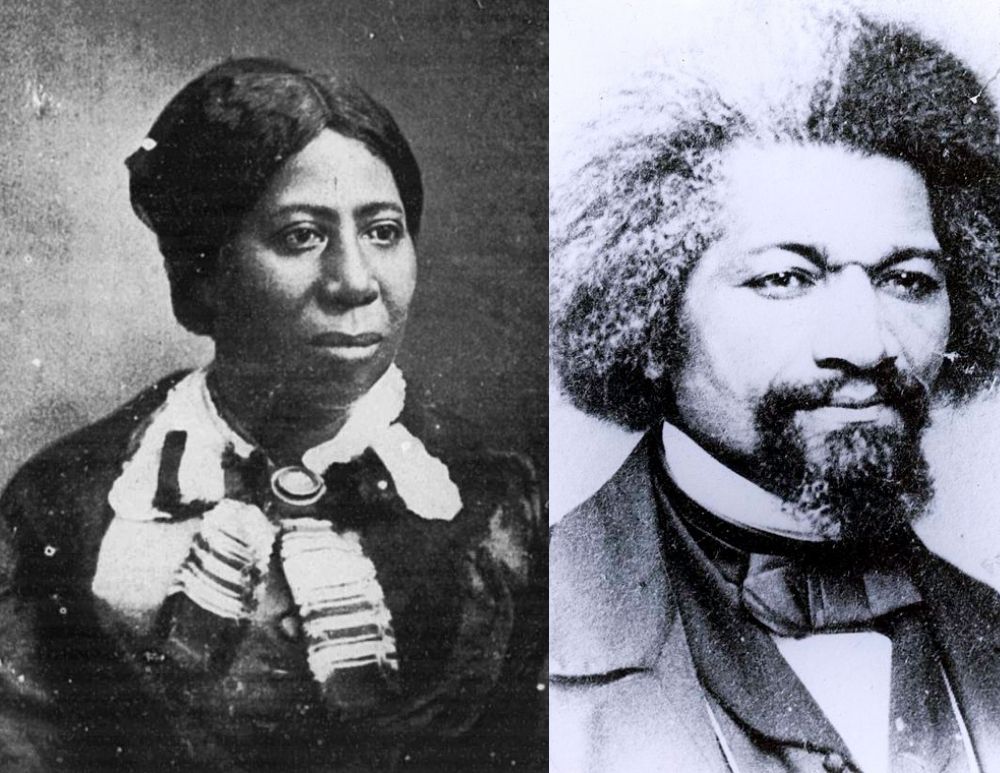

On a warm August afternoon in 1882, 3,000 family, friends, and acquaintances gathered to pay their respects to Mrs. Anna Murray Douglass. She was the wife of Frederick Douglass and mother of five children; an activist, abolitionist, homemaker, and a sister and friend. Rev. Dr. William Waring officiated the service and preached from the New Testament book of Matthew. Anna Murray Douglass and her loved ones did not know when she would go to her final resting place. She had been sick for a month, suffering from a stroke that led to paralysis, while her family and close friends attended to her. But she was called home after 69 years of life, the majority (44 years,) married to the “great orator and abolitionist,” Frederick Douglass. We see her at flashpoints in her husband’s political and very public career and get glimpses of her private life through family and foe. Douglass’s biographers mention but never dwell on her. Who was Anna Murray Douglass?

Most people know her as the first wife of the most famous African American leader of the 19th century. Her daughter Rosetta Sprague provides the most convincing description, reminding readers that her mother’s identity was so immersed with her fathers, that few people truly understood or “appreciated the full value of the woman who presided over the Douglass home for forty-four years.” But she also noted how hard it is to talk about her mother “without mention of father” because “Her life was so enveloped in his.” As a result, much of what is known about her has been shared through his life.

I begin my journey into Anna Murray Douglass’s life at the end. Her death symbolizes her life, in and out of the shadows of her husband. Thousands came to pay their respects to celebrate the life of a remarkable woman, not just a wife. Her granddaughters and “other women” prepared the body for the burial ceremony, which was held in the front parlor at Cedar Hill,” a place she called home for 10 years, not far from the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. Immediately following the service, a procession of 100 carriages and “a great number on foot” proceeded three miles to Graceland Cemetery where she was laid to rest.1

Anna Murray Douglass was a conductor on the Underground Railroad and her future husband was her first passenger. She was the mother of five children and she attended to their education, development, and growth. She was also a working mother, who held jobs inside and outside of the home while serving as the family “banker.” She was an activist supporting abolition and women’s rights and attended meetings of the East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society, Lynn [Mass.] Ladies Association, and other Anti-Slavery Societies in New England. She spent much of her adult life entertaining guests in the Douglass family homes including some of the most influential leaders in American history such as Henry Highland Garnet, Harriet Jacobs, and Amy and Isaac Post.

I am working on a biography of Anna Murray Douglass contracted by Yale University Press’s Black Lives Matter Series. My goal is to present her as a Black woman who did all she could to support her family and surround herself with other Black and white women activists, while also maintaining a full house of children, grandchildren, visitors, and friends. She was a strategist in her own right who added depth to the intellectual base of the abolitionist movement. My goal is to highlight her contributions and thoughts by searching for her in the archives, memories, and organizations that she came into contact with. However, any scholar of Black women’s history knows that there is a well-established set of methodological practices aimed at recovering Black women from the archive, searching for their voices in movements, and finding their stories hidden within a variety of spaces, places, and events. Historians such as Evelyn Higginbotham, Nell Irvin Painter, Barbara Ransby, Chana Kai Lee, Wanda Hendricks, Catherine Clinton, Sherie Randolph, Keisha Blain, and Margaret Washington who have written biographies on Black women write as detectives seeking Black women’s experiences and bringing them to light. We bring texts together around central themes and methods that push beyond dissemblance, respectability, and dispossession, making way for new categories of analysis that can speak to Anna’s experiences as a “domestic activist,” one who used her home as a space for change.2 Anna’s story will be different because one cannot write about Anna Murray Douglass the same way one writes about Frederick Douglass, using the same tools and methods.

As I embark on the first full-length study of Anna Murray Douglass, I hope readers grasp how she was a leader in her own right who used domestic spaces as sites of political activism. I hope to take the reader on a journey through slavery and freedom in Maryland, New England, New York, and our nation’s capital. The biography sheds life on African American family, humanity, and activism. It also bears witness to the abolition of slavery and the Civil War, including the rights of Black soldiers. When her life came to an end, and her body was laid, the story of Anna Murray Douglass continued in the lives of her surviving children and grandchildren. It continues today as her descendants celebrate the extraordinary life of this understudied yet tremendously influential family matriarch.

- Graceland Cemetery, founded in 1872 for African Americans was not her final resting place. Anna would later be exhumed and reburied next to her Frederick Douglass at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, NY. ↩

- The term, “domestic activist” is a placeholder for a concept I am developing to address women who used their homes to influence, indulge, and intervene in causes they supported. In addition to raising children, women like Anna contributed to 19th-century social change in unrecognized ways. ↩

Professor Berry, thank you for this article. I am excited to know you are working on a bio of Anna Murray Douglass! And I love your concept of “domestic activist.”

Mark Higbee, Eastern Michigan University

Yes, finally! Thank you so much for this important work. I have spent years frustrated to read subtle yet sexist accounts that characterised Frederick Douglass as “ashamed” that his wife wasn´t “literate”. That as he grew into his intellecutal status he grew apart from Mrs. Douglass. And not a single word beyond her being a good homemaker eventhough she herself was an Abolitionist, a conductor on the Underground Railroad, as well as a wife and mother. Excited to see what her fully imagined life looks like as both/and and not either/or.

This is a great project- which allow everyone to better understand the Black Freedom Struggle in America. The role of the Black mothers for freedom- we are excited to read more. Thank you for this contribution. God bless.