Sara Baartman, Say Her Name: A Bicentennial Anniversary

One of the stranger stories that broke with the new year was the report (now discredited) of pop star Beyoncé writing and starring in a new film on Sara Baartman (ca. 1790-1815), South African national hero once widely known as the “Hottentot Venus.” Despite the various outrages this story provoked – from South Africans, who believed the pop star is an inappropriate representative, to African Americans who took offense over the implied body politics and differences between Africans and African Americans – few have noted how the prevalent fetishism of both historical and contemporary black womanhood framed their bodies through sexual stereotypes as “bum women” (as first characterized by The Sun tabloid, which started the rumor). However, the best statement came from Beyoncé’s publicist, who reminded the public that Baartman’s history is “an important story that needs to be told.” Indeed, the French film, Venus Noire, already came out in 2010, despite my own reservations of how that film perpetuated the silencing of Baartman’s voice and perspective.

One of the stranger stories that broke with the new year was the report (now discredited) of pop star Beyoncé writing and starring in a new film on Sara Baartman (ca. 1790-1815), South African national hero once widely known as the “Hottentot Venus.” Despite the various outrages this story provoked – from South Africans, who believed the pop star is an inappropriate representative, to African Americans who took offense over the implied body politics and differences between Africans and African Americans – few have noted how the prevalent fetishism of both historical and contemporary black womanhood framed their bodies through sexual stereotypes as “bum women” (as first characterized by The Sun tabloid, which started the rumor). However, the best statement came from Beyoncé’s publicist, who reminded the public that Baartman’s history is “an important story that needs to be told.” Indeed, the French film, Venus Noire, already came out in 2010, despite my own reservations of how that film perpetuated the silencing of Baartman’s voice and perspective.

In the wake of the bicentennial anniversary death of Baartman, it is instructive to reflect on her posthumous legacy. Immediately after her death in Paris in late December 1815, she was subjected to anatomical examination by Napoleon’s Surgeon General and baron George Cuvier, a natural scientist who dissected her brain and genitalia and preserved them in jars of formaldehyde fluid, marking them as emblematic of a “race” of people and thus labeling sub-Saharan Africans with embodied signs of intellectual inferiority and heightened sexuality. Decades later, the “Hottentot Venus” exhibition that marked Baartman’s entry into the sideshow circuits of England and France proliferated with different “performers” fulfilling stereotypes around bestial and primitive sexuality relating to the posterior, thereby resulting in racialized tropes that framed the bodies emerging from the African continent, and the southernmost tip in particular since the derogatory term “Hottentot” suggested a people, living on the Cape of South Africa, as “missing links” between humans and apes.

Two centuries later, Baartman has been resurrected in the late twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries as an icon and theoretical foundation for discourse on black female sexuality. Sometimes twinned with her American counterpart – the enslaved black woman – Baartman became a stand-in for racialized and gendered otherness in the white, Western, and imperial imagination, as well as a symbol for reclamation in decolonized and black diasporic movements. This latter point is best illustrated by the efforts of a post-apartheid South African government, which agitated for the return of Baartman’s remains, housed at the time in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. She was finally returned and buried along the banks of the Gamtoos River in 2002, and the Sarah Baartman Centre of Remembrance is currently in development near her burial site.

When I chose to focus my dissertation on Sara Baartman, which later became my first book, Venus in the Dark, my adviser was far from appreciative. She is a staunch literary historian whose primary research goals are the recovery and reclamation of black women’s historical voices – especially those voices that were most resistant to the prevailing stereotypes surrounding black female sexuality. I was adamant in my decision, however, so I received a stern warning that I would be perpetually associated with a fetish and a subject matter that would prove difficult in transcending its fetishization.

When I chose to focus my dissertation on Sara Baartman, which later became my first book, Venus in the Dark, my adviser was far from appreciative. She is a staunch literary historian whose primary research goals are the recovery and reclamation of black women’s historical voices – especially those voices that were most resistant to the prevailing stereotypes surrounding black female sexuality. I was adamant in my decision, however, so I received a stern warning that I would be perpetually associated with a fetish and a subject matter that would prove difficult in transcending its fetishization.

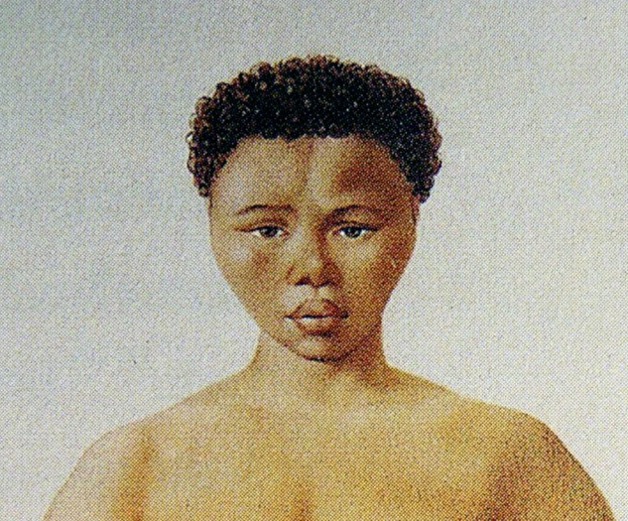

In tracing a history that included no letters, poems, or narratives “written by herself,” the quest for Baartman led me to the remnants of her body as I quite literally stumbled upon her skeleton (before it was finally removed and returned to South Africa for burial) and the plaster cast molded by Cuvier at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, as well as various nineteenth-century sketches, paintings, and cartoons – the latter already a distortion of the historical figure etched within contexts not always perceptible to a twenty-first-century audience.

Because of these limitations, there are pitfalls to researching Baartman and disseminating knowledge concerning her troubled history. Consider the following reactions to the different presentations that I have delivered on this work, or even to the ways that other scholars have tried to elicit or comment on this history:

*At a job talk based on my dissertation research – which I had just completed back in 2001 – a white doctoral student responds to my subject matter during Q&A by remarking on her own research on the history of flight attendants, stating that my lecture helped explain why black flight attendants needed their own uniforms that could accommodate their supposedly big behinds, instead of the regulated ones fitted for white attendants.

*After this same job talk, I was cornered by a future black colleague who proceeded to chastise me for perpetuating racist logics (as the white doctoral student’s comments suggested) that viewed black women as inherently different due to our bodies; she worried that my lecture reiterated the worst stereotypes of black womanhood, which her own research on “respectable” black club women in late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century New York sought to counter.

*At a speaking engagement highlighting “emerging scholars in women’s studies,” an elderly white woman scholar consulted me afterwards, wanting to know if the plaster cast of Baartman’s body – shown in my slide show – didn’t “prove” that there was something inherently “strange” and “abnormal” about the size of Baartman’s buttocks. She at least was racially conscious enough to ask me this question privately, and not during the public Q&A session; however, she was not conscious enough to know this line of thinking was inappropriate.

*At a local conference at my university, I eschewed images of Baartman in hopes that the audience would not get sidetracked by visual reinforcements of racial and sexual “difference.” And yet, the subject matter was enough to evoke a question from a middle-aged white woman scholar who asked me if it were not true that the original strip tease/exotic dancers were West African dancers. Somehow, even the subject of Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus,” immediately calls to mind for some audiences the entire African continent – a perpetual signifier of sex, libido, nakedness, uninhibited dancing, and the ultimate primal void that any white person can connect to (provided they shed their “civilized whiteness” and their Europeanness).

*At an annual meeting of the National Women’s Studies Association, a white anti-porn feminist scholar presented on racist and misogynistic portrayals of black men and white women in interracial porn. However, before she examines her subject matter, she begins with an early photograph (perhaps dating in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century) of an African woman in “tribal dress” whom she mislabels Sara Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus.” This image supposedly represented black sexuality as “primitive” and “hypersexual,” themes that categorized interracial porn. That the photograph didn’t even feature the African woman in the usual pornographic poses that emphasize the size of her buttocks (she was depicted in a frontal pose, so no signification of her size even existed within these visual parameters) suggests the presenter’s misreading of Venus iconography. Moreover, her presentation’s focus had nothing to do with black women’s sexuality as she was only interested in black men and white women in pornography. Baartman, and black women by extension, was simply invoked to represent the “basest” in human sexuality. Her stunned response when I and several other black feminist scholars in the audience called her out on her flawed scholarship indicates the ways that present-day scholars and audiences are unconscious of their dehumanizing gaze and the reduction of Baartman’s history to objectification and devaluation.

*In writing an updated article for peer-reviewed journals, in commemoration of Baartman’s bicentennial, external reviewers struggled over her “continued relevance” as a symbol of black, African, and/or subaltern sexualities, thereby strongly recommending that her troubled history be finally put to rest.

Because I will be spearheading a Roundtable Discussion next month at the University at Albany, I realize that I refuse such scholarly dismissals, while also recognizing the political and cultural controversies that Baartman’s history still provokes. From stepping into the French-South African tug-of-war when I first researched Baartman in Paris in 1999 to reflecting on this year’s various “outrages” over any invocation of Baartman to puzzlement over the local vandalism of Baartman’s burial site, we have not yet reconciled with her multifaceted meanings when it comes to race, gender, sexuality, disability, nationality, and transnational struggles. At the risk of once again opening up old wounds, I propose that we all confront Baartman’s painful history. We still need healing from it, which can only come about once we reclaim her body and envelop it into our own collective body politic – no matter where we reside in the Black Atlantic World. Baartman’s legacy can still be felt: in the hyper-sexualization of the black body or in the continued apartheid practices that relegate people of African descent to the lowest rung of economic, social, political, and cultural opportunities. Once we #sayhername (and The Sun felt compelled to do so on this her bicentennial), we resurrect her ghost and a powerful memory of the dangers of dehumanization.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.