Rio’s Carnival Quilombo

This post is part of our forum on “Race and Latin America.”

Brazil’s Carnival is widely imagined as a locus of racial equality, sexual liberation, and artistic expression; a feast for both locals and visitors that allegedly blurs all boundaries. Despite this dominant image of inclusive festivities, the larger historical context reveals a much more fractured scenario. Carnival is not void of political disputes, internal disagreements, and competing views on its meaning, nor is it free from whitewashing and commodification. A recent 2019 parade by Mangueira samba school included a large banner with the words “Índios, negros e pobres” (“Indigenous, Black, and poor people”), suggesting a renewed attention to racial justice and critical carnival performance. In 2022 Grande Rio samba school provided a strong message in favor of Afro-Brazilian religions, which have been threatened by rising Neo-Pentecostal Evangelicalism. The parade featured Exu/Eshu, a prominent figure in candomblé, represented by Black dancers in his original attire. Historically Exu/Eshu has been ostracized and misinterpreted by some Christian denominations as the devil. However these recent examples contrast with a process of commodification and whitewashing that peaked in the 1970s and still thrived in many desfiles until the 2000s.

By the end of the 1950s, Rio de Janeiro’s world-famous carnival went through major whitening and commodification transformations. As examined by historian Guilherme Motta Faria, a fine arts professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Fernando Pamplona, played a key role in whitening Carnival. Pamplona directed the parade of the traditional samba school Acadêmicos do Salgueiro, headquartered at an homonymous Black-majority favela. In 1960 Pamplona invited Marie Louise Nery, Dirceu Nery, and costume designer Arlindo Rodrigues to assemble a parade. All of them were white, and Marie Louise was even Swiss. Pamplona eventually used his academic background to do what Faria alludes to as a process of “professionalization” of Carnival, in which carnavalesco came to describe the post of Carnival organizer and artistic director. The aesthetic and managerial shift under Pamplona came to be known as the “revolução salgueirense,” the Salgueiro School revolution. It involved a greater participation of Carnival “specialists” from outside Black-majority neighborhoods, often hailing from middle and upper-class backgrounds.

From a commercial perspective, the alleged revolution contributed to the transformation of Carnival into a tourist attraction and sales event. By the mid-1970s Rio’s Carnival became a large-scale spectacle. Samba School Beija-Flor marched with luxurious and expensive costumes in 1974 and 1975, in parades that also included sumptuous floats. The luxurious and eye-catching appeal of such parades created a schism among the people of Carnival. Many questioned the attenuation of Black narratives in Carnival, evident in changes in Carnival song themes, spatial distancing from the everyday life of Black-majority neighborhoods, participation of outsiders, and the new tourist-oriented luxurious parades.

Antônio Candeia Filho was a critic of this two-fold process. He was known in samba circles as Candeia, meaning “a source of light,” Candeia was a founding member of Portela, one of the “Big Four” samba schools that often disputed and won Carnival competitions. Other Big Four members included Salgueiro, Mangueira, and Império Serrano. As a Black sambista and advocate of Carnival’s African roots, Candeia opposed the whitening of Carnival themes and membership. As seen in a Correio Braziliense interview, he also contested the increasing commercialization of the festival, which included increased pressure from the phonographic industry that pushed Carnival schools to record their yearly songs well before Carnival to secure album sales. Three consecutive wins by Beija-Flor (1976, 1977, 1978), which had incorporated Pamplona’s formula, shook the Big Four. Many members of the traditional schools, including those hailing from whiter neighborhoods, thought they had to adapt and catch up with Carnival’s inevitable “new era.”

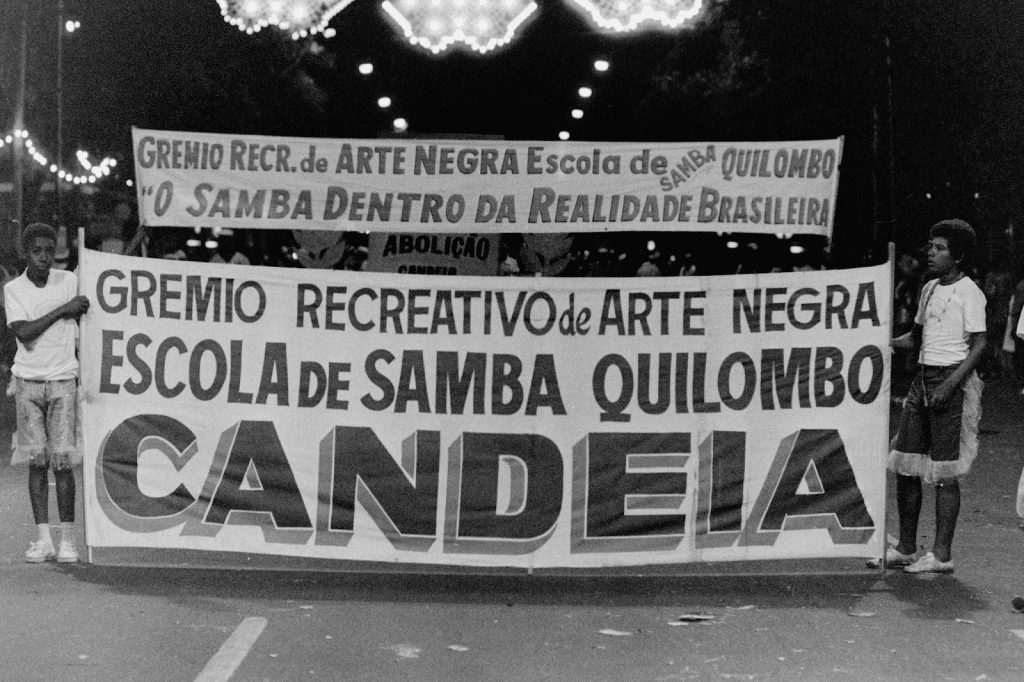

Around 1975 Candeia, alongside other Portela musicians and sambistas like Paulinho da Viola, took a break from Portela. They founded a new samba school, Grêmio Recreativo de Arte Negra e Escola de Samba Quilombo (GRANES Quilombo), to counter Carnival’s new format and reclaim its Afro-Brazilian roots. Candeia openly questioned the interference of white academics in samba schools. He asserted schools had “their own culture and Afro-Brazilian roots” and opposed luxurious floats which had taken too much of schools’ efforts, eclipsing samba performances on foot.1 Candeia also argued the alleged “intellectuals” who had joined Carnival planning and execution had occupied creative spaces in samba schools, and the hiring of non-Carnival songwriters contributed to the “gradual extermination of anonymous composers, looking for their place under the sun, an opportunity.”2 In December 1975, the GRANES Quilombo emerged with bright yellow to honor Oxum/Oshun, lilac to represent quilombo flowers, and white for peace. Other prominent sambistas and musicians such as Paulinho da Viola, Isnard Araújo, Monarco, and Wilson Moreira joined the new association. In Candeia’s words to the Correio, the Quilombo was a new reference, without “patrons of the arts, nor scenographers applying their ‘good taste’.”

GRANES Quilombo created lasting impacts beyond Carnival parades. It fostered community events in the North-side neighborhood of Coelho Neto. It recreated the atmosphere of samba-de-quadra, or the samba produced in Black neighborhoods, where community members made music throughout the year and congregated without external pressures or demands from a commodified event. To Candeia, samba schools had turned their backs on Black sambistas who had historically resisted oppression. Their culture was little known by Rio’s white middle and upper classes, who ignored what happened in the metropolitan area’s Black-majority neighborhoods. The GRANES Quilombo contested the 1970s format of carnival. Samba schools, lured by a dominant white ideology, saw themselves inserted in a whitening process, akin to other transformations linked to the legacy of slavery in Brazil. In that process, costume and float designs were made according to the aspirations of their designers, who disregarded samba school membership and their social interactions, taking advantage of Black people’s cultural production and disenfranchisement. Candeia’s critique identified the interference of outside professionals as part of a broader pattern that encouraged a false duality of “erudite whites” and “illiterate Blacks.”

The busy gatherings in Rio’s North Side quickly attracted crowds. Lélia Gonzalez, acquainted with Paulinho da Viola, joined meetings and celebrations in Rio’s North-side. She once cited the GRANES Quilombo as an example of cultural production that opposed the commodification and “folklorization” of Black cultural production.3 By centering its activities around community spaces and events and rejecting the rules set forth by Carnival organizers, the GRANES Quilombo chose not to join Carnival competitions. In 1978 it paraded in a different, non-traditional avenue of Rio’s downtown in the financial center. This desfile commemorated the ninetieth anniversary of emancipation.

Candeia passed away in 1978. In the 1980s, GRANES Quilombo turnout decreased until the school finally disappeared. The GRANES Quilombo left a legacy of Afro-centered critique that recalls the notion of aquilombamento, or “to become a quilombo.” By taking public spaces to demand racial justice, contest white dominance, and reconstruct Black community sites of congregation and cultural life, their work ties to Joselicio Júnior’s definition of the concept, or “constructing spaces where one can reflect and act over our reality. Question what is posed, what . . . oppresses, and builds demands, concrete actions.” While short-lived, the GRANES Quilombo left a legacy of Black-centered critique that inspires a reappropriation of practices, cultural production, and spaces threatened by white-commodified interests. Candeia’s words and ideas still inspire actions inside and outside the streets of Carnival.

- Antonio Candeia Filho and Isnard Araujo, Escola de Samba: árvore que esqueceu a raiz (Editora Lidador and SEEC-RJ, 1978). ↩

- Candeia Filho and Araujo, Escola de Samba: árvore que esqueceu a raiz, 1978. ↩

- Lélia Gonzalez, Por um feminismo afro-latino-americano: Ensaios, Intervenções e Diálogos, ed. Flavia Rios and Márcia Lima (Rio de Janeiro: Editora Schwarcz, 2020), pp. 73-74. ↩

Thank you for this amazing work! Im a afrobrazilian woman living in the US, and is great to find good content about black communities in the Americas, even more in Brasil.