Rethinking H. Rap Brown and Black Power

Conversations in Black Freedom Studies (CBFS) is a monthly discussion series held at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Curated by Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, the series was established as a space to discuss the latest scholarship in Black freedom studies, bringing the campus and community together as scholars and activists challenge the older geography, leadership, ideology, culture, and chronology of Civil Rights historiography. In anticipation of the planned discussion on Rethinking H. Rap Brown and Black Power, scheduled for Oct. 4th, we are highlighting the scholarship of two of their guests.

Akinyele Umoja is a Professor and the Chair of the Department of African-American Studies at Georgia State University. He is also the author of We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance and the Mississippi Freedom Movement (New York University, 2013). Along with Mayor Chokwe Lumumba and others, Umoja is also a founding member of the New Afrikan Peoples Organization and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement. Follow him on Twitter @BabaAk.

Arun Kundnani is the author of The Muslims are Coming! Islamophobia, Extremism, and the Domestic War on Terror (Verso Books, 2014) and The End of Tolerance: Racism in 21st Century Britain (Pluto Books, 2007). He teaches at New York University and Queens College and is a former editor of the journal Race & Class. Follow him on Twitter @ArunKundnani.

CBFS: Can you tell us about your research and how you came to study and write about Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin (H. Rap Brown) and Black Power?

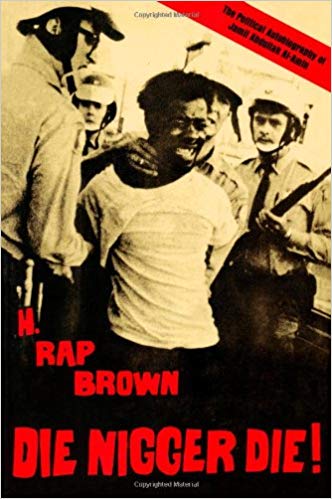

Akinyele Umoja: I first heard of H. Rap Brown (Jamil Al-Amin) when he was a spokesman for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1967. I was in junior high school at the time, living with my parents in Compton, California. His speeches and image on the news was inspirational to me. It was two years after the Watts Revolt and Rap was one of the spokespersons who best articulated the rage of the rebellions that I witnessed in Watts and others occurring in urban centers throughout the United States empire. I looked and found information about him to gain more clarity. I first read his book Die Nigger Die when I was in high school.

I first met Jamil Al-Amin after I moved to Atlanta in 1984. We had several conversations at his grocery store on the westside of the city. Later, he was arrested for shooting two Fulton County police officers. I served as a research consultant to Jamil Al-Amin’s legal defense team during his trial in Atlanta from 2000-2002. This is what led me to begin researching his life and political activity. I also had the opportunity to visit and interview him in Fulton County Jail. I’m completing an article focused on political repression against H. Rap Brown.

Arun Kundnani: In my book, The Muslims are Coming, I examined the cultural and political dynamics of the War on Terror and its effects on Muslims living in the United States. One of the cases I looked at was the 2009 FBI killing of Luqman Abdullah, a Black Muslim leader in Detroit. To understand who Abdullah was, I needed to study Jamil Al-Amin, the leader of the religious organization he belonged to. It soon became clear that the story of Al-Amin encapsulated many of the topics I had worked on in my first two books: political radicalism, state violence, surveillance, and racial capitalism. Writing his biography seemed to be a way to relate the 1960s to the present day, the Black experience to the Muslim experience (he converted to Islam in 1971), and domestic to international political struggles, in intellectually and politically productive ways.

Rap Brown was a household name in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a regular on national television, and one of four men listed in the famous 1967 FBI COINTELPRO memo that targeted the Black freedom movement. Over the last eighteen months of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, the White House received near-daily memos from the FBI on Rap’s activities. Rap’s 1969 book Die Nigger Die was said to be the most read in the US prison system. State and federal law enforcement pursued him relentlessly for three years before he went underground. Today, he is incarcerated in the federal prison at Tucson, Arizona, where scholars and journalists are not permitted to speak with him. Challenging this policy has become a necessary part of my work.

Rap Brown was a household name in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a regular on national television, and one of four men listed in the famous 1967 FBI COINTELPRO memo that targeted the Black freedom movement. Over the last eighteen months of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, the White House received near-daily memos from the FBI on Rap’s activities. Rap’s 1969 book Die Nigger Die was said to be the most read in the US prison system. State and federal law enforcement pursued him relentlessly for three years before he went underground. Today, he is incarcerated in the federal prison at Tucson, Arizona, where scholars and journalists are not permitted to speak with him. Challenging this policy has become a necessary part of my work.

CBFS: Can you share a story from his history of organizing that our readers might not be familiar with?

Umoja: When it was announced that Rap Brown would be Chairman and primary spokesperson for SNCC in 1967, he was virtually unknown to the national media. Brown came into the movement following the path of his older brother Ed, who had enrolled in Howard University after being expelled from Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s historically Black Southern University. After graduating high school, instead of pursuing a promising athletic career, Rap came to DC to work with his brother Ed in the Nonviolent Action Group, SNCC’s organization on Howard’s campus. Rap involved himself in SNCC activity while visiting his brother. He represented SNCC at a meeting at the White House to confront President Johnson to provide federal protection for voting rights workers in Selma, Alabama. His willingness to vocally and militantly challenge President Johnson in the meeting is the first time he received a mention in the national media.

H. Rap Brown later worked in the Alabama Black Belt to create political alternatives to the Democratic and Republican parties. In particular, in 1966, he organized an independent freedom political party in Black majority Greene County, which used a black panther as its logo. SNCC pursued building independent political parties in Black majority counties in the state since the Alabama Democratic Party openly endorsed segregation and white supremacy. SNCC worked to build these parties or freedom organizations in Alabama, notably in Lowndes County. The building of the Alabama freedom organizations initiated the Black Panther political movement in the United States and globally. His work in DC and in Greene and Lowndes counties in Alabama solidified his reputation as a Black Power spokesperson for SNCC.

Kundnani: The internationalism of the Black Power movement is often understated. Rap embodied the sense that the Black freedom struggle was intertwined with anti-imperialist struggles around the world: in 1967, he was the first Black leader to speak publicly in solidarity with Palestine; in 1971, he visited Tanzania, where leaders of southern African liberation movements were based. Over the course of his life, he built relationships with revolutionary movements in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and Sudan.

Above all, Rap was someone who inspired others to act. He communicated political ideas in the language of the street. From the community response to racist policing in Detroit, to the founding of the Last Poets, and the protests at the 1968 Olympics, he is repeatedly cited as an agitator and instigator. Those who worked with him mention, above all, his bravery. At a certain point, he expected that his life would be ended but he continued his activism. When a bomb went off in his car, killing two of his comrades, he went underground. But rather than choose the safety of exile in Cuba or Algeria, he headed for Harlem to take on the drug barons and their links with the New York Police Department; all this while he was still in his mid-twenties.

CBFS: Given the continuing struggles for racial justice today, how does this history help us understand or act in our current moment?

Umoja: Rap Brown was one of the most important orators of the Black Power movement. Before the advent of social media, his voice and spoken word reflected the rage and rebellion of Black youth during the 1960s. As Rap Brown his image became synonymous with Black resistance and revolution. Like Malcolm X, Rap Brown distinguished between expressions of Blackness, which supported the status quo, and representations that were radical and transformative. His word and thought must be interrogated for the Black Lives Matter generation and current manifestations of resistance.

Kundnani: So many of the questions Rap and his colleagues were wrestling with continue to be central to our movements today. Like them, we are trying to figure out how the fight against white supremacy intertwines with the struggle against capitalism. Like them, we are trying to understand how to connect our struggles in the United States with radical movements around the world. And like them, we are doing so while trying to survive and overcome the state’s immense capacity for violence.

In some ways, we have learned from the mistakes of movements of the past, particularly around their masculinism. But in other ways, their work embodied political wisdom that we have lost: for example, Rap’s organization, SNCC, combined a grassroots, radically democratic base in communities with a capacity for sophisticated strategic planning, informed by detailed analyses of power structures. We should also remember that Al-Amin is currently in prison in what I believe was one of the first of many unfair trials of Muslims after 9/11; part of our struggle today is to address those injustices which appear to be, in many ways, a continuation of the COINTELPRO practices of the 1960s. The past is not past.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for this interview. This history, and the current situation of Al-Amin need to be known.

Jamil Al-Amin is an innocent man. His continued imprisonment and persecution are completely unjust!!!

Thank you for this insightful interview. Imam Jamil Al-Min mentored me when I was an undergraduate at Morehouse College. We played basketball with each other across the street from his store in the the early 90s. He talked a lot smack on the basketball court like brothers do in a fun and loving way. We also talked extensively about the movement, his history and his conversion to Islam. He always expressed concern about how I was doing in school and the like. Phenomenal human being and real pillar in the community.

I agree with Kundani’s comment that, “The internationalism of the Black Power movement in often understated.”