Rethinking Black Life on Turtle Island

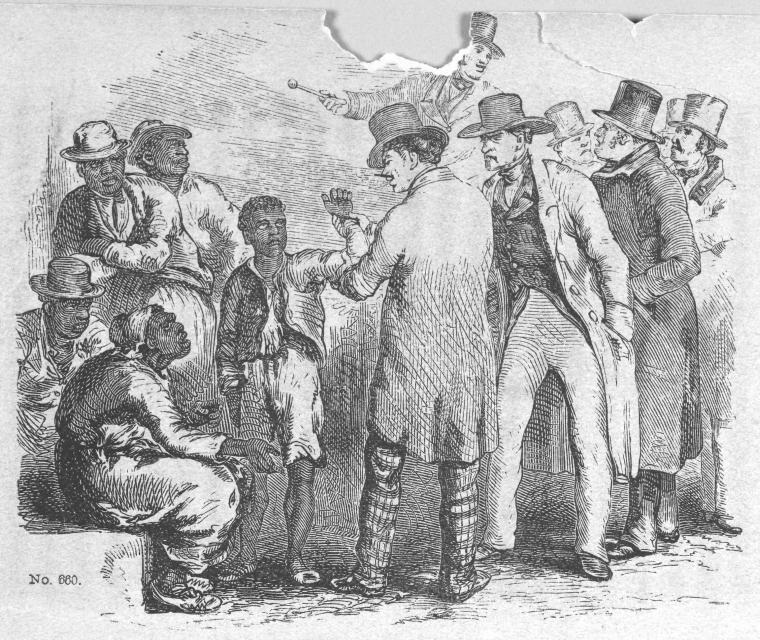

The history of Black peoples in Canada prior to the mid-nineteenth century is a complex and transnational story. In popular histories, Canada remains a place where the North Star is brightly illuminated, both for those who traversed the Underground Railroad and those who arrived as “Black Loyalists” in the Maritimes after the American Revolution and War of 1812. However, a historical study of Black life in Canada reveals betrayals of freedom and radical patterns of racial displacement within the nation and beyond its borders, as well as Black enslavement from the early 1600s until 1834. In my own research, I employ the theoretical term, “metamigration,” as an attempt to encapsulate the distinct violence experienced by a people—some emancipated, others captive—constantly in movement and explicitly directed by de facto patterns of racial segregation. Historian Harvey A. Whitfield has pointedly described this history in his 2017 monograph North to Bondage about slavery in the Maritimes:

“Re-enslavement, the expansion of slavery, fear of sale to the West Indies, the spectre of living in a society with slaves, brutal forms of indentured servitude, and inequality were as definitive to the African and African American experience in the Maritimes as the hopes of freedom that accompanied the Black Loyalist migrants to His Majesty’s northern possessions” (52).

In addition to the forced displacement that marked Black life in Canada in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Black people lived with a specter of racial violence that followed them across the northern border. In the early nineteenth century sundown laws were informally in effect, in towns like Priceville, Ontario, where self-emancipated African Americans attempted to make a home. In the latter nineteenth century, false allegations of interracial rape, threats of lynching, and the presence of white supremacist organizations reinforced the trope of the Black rapist and ensured a spatial organization of dominance for those migrating to Canada. As historian Sarah Jane Mathieu explained, “In the years leading up to World War II, white Canadians repeatedly presented lynching as an inevitable way of policing Blacks in Canada, as though homicidal rule were a natural course of race relations.”

In her recent book, Tropical Freedom: Climate, Settler Colonialism, and Black Exclusion in the Age of Emancipation, historian Ikuko Asaka undertakes an expansive transnational study about Black displacement and colonization efforts in Canada and the U.S. between 1780 and 1865. Alongside her thesis that biological determinism justified Black “dislocation to tropical regions” and ensured economic and social marginalization “in the metropoles and on continental frontiers,” Asaka’s study also explores “the intersections between Black freedom and settler colonialism” (17).

This timely work contributes to a long arc of scholarship over the last decade led by Black and Indigenous scholars such as Tiffany King, Shona N. Jackson, Jared Sexton, Frank B. Wilderson III, Sharon P. Holland, Tiya Miles, Allison Guess, Sandy Hudson, and Jodi Byrd about the relationship between Black life in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and settler colonialism on Turtle Island, a spiritual referent in North America for some First Nations peoples. These writings are of particular import for scholars who trace the histories of Black slavery, migration, and dispossession beginning in the seventeenth century throughout the territories now known as Canada. While these conversations are diverse, one central, contested argument is that Black migrants also constituted settlers on Turtle Island—and at the very least, were historically invested in settler logics, given broad political struggles to be included in citizenship and “rights” frameworks deemed antagonistic to Indigenous sovereignty. Concurring with a fraught 2005 article in her opening chapter, Asaka writes, “In thinking about freedom and settler colonialism, one should keep in mind that aspirations for landholding by the emancipated were ‘premised on earlier and continuing modes of colonization of indigenous peoples” (18). In her conclusion, Asaka returns to this point: “The codification of Black rights to become settlers was a paradigm shifting development” which made Black peoples “the legal beneficiaries of the official apparatus of native land divestiture” (197-8).

Close studies of Black history in Canada reveal complex patterns of Black “unsettlement,” historically, within the nation. King has argued that these “unusual landscapes” require a rethinking of “the usefulness of convenient and orthodox epistemic frames.” Specifically, theorist Katherine McKittrick has stated that Black Canadian Studies “can only be an interdisciplinary and diasporic undertaking” with “intellectual and creative and historic narratives that are always locally outer-national” (236).

As such, many have resisted narrow arguments about early Black peoples’ relationship to settlerhood, insisting upon the need for more generous, nuanced reflections of early Black life on Turtle Island. Discussing the obtainment of natural and legal rights after legal emancipation in the U.S. context, Saidiya Hartman describes the “burdened individuality of freedom” and asks whether or not it was ever truly “possible to unleash freedom from the history of property that secured it” (119). Jared Sexton and King have both insisted that settler colonialism is “constitutive to antiblackness” and that any well-rounded critique of settler colonialism in the Americas must also critique Blackness as an abject position—one that both served as a pre-condition for settler colonialism and the ubiquitous logic of white supremacy.

Relatedly, historians such as David Brion Davis have made explicit the global connections between Blackness and enslavement well before 1400, paying close attention to “medieval Arabs and Persians who came to associate the most degrading forms of labor with black slaves” (62). On the point of labor, King has written that the particular condition of Black enslavement—“fungibility”—means that enslaved bodies “are the conceptual and discursive fodder through which the Settler-Master can even begin to imagine or ‘think’ spatial expansion” and are thus, “outside the edge and boundary of laborer-as-human.” Responding to arguments regarding sovereignty, Sexton has referred to its necessary loss in the history of global enslavement as a “fait accompli, a byproduct rather than a precondition” (593). He has raised a provocative question regarding Black and Indigenous histories on Turtle Island: If it can be said that the field of Black Studies entails “tracking the figure of the unsovereign,” then is the problem inherently with the notion of sovereignty “as such”? In other words, he concluded, abolition—a specific foci of struggle for Black peoples in North America—remains “beyond (the restoration of) sovereignty” (593).

I want to propose another thread. Interwoven throughout the works of historians of slavery in North America, such as Harvey A. Whitfield, Charmaine Nelson, Stephanie M. H. Camp, Edward Baptist, Daina Ramey Berry, Sharla Fett, and Stefanie Kennedy to name a few, are also details of the relationship between Black peoples and the lands they were continually “out of place” on. To understand Black survival prior to the mid-nineteenth century in Canada and the US is to also witness a sacred stewardship for the earth on which Black people knew that their lives depended. In an economy built on the maximum extraction and profit from the Black body, in three crucial ways, Black enslaved and self-emancipated peoples related to the land as food, medicine, and a cartography of resistance.

Black enslaved peoples cared for their lives and their families’ lives with opportunities, albeit infrequent, to grow vegetables on small plots of land. Fresh vegetables, Berry has written, were generally not included with the nutritionally poor, cast-off rations tossed to enslaved families. To grow something green or bright orange or red meant something to mothers whose children often wasted away before age five—mothers whose deceased children could also be sold as cadavers to medical schools for an owner’s $20 gain. To sell what the earth yielded, if one was able, also sometimes meant pocketing side monies that could eventually be used to purchase one’s child or one’s kin.

The land also provided medicine, and elder “healers could read the woods just like a book” (64). Medicine meant healing a body that could not be disposed or cast aside to die because white doctors were deemed too costly of investments for many enslaved people. Disabilities amongst the enslaved—a broken leg or tumor—were weighed in strictly profit/loss terms by owners; enslaved women who knew plants also knew how to care for the most vulnerable within enslaved communities—children, the elderly and disabled. In her work, Fett refers to enslaved people’s “sacred relational view of health and healing” arising from a “spiritual relationship to the land” – one that “shared similarities with herbal practices arising under slavery throughout the Black Atlantic” (62).

And of course, enslaved people ran all the time, stealing their freedom as truants and fugitives. To journey with the North Star, meant learning and trusting the land, its streams, creeks, and other bodies of running water. To run, as Harriet Tubman understood, was to know the stars by name, as well as their constellation families.

As stewards for the land, Black people offered generative care and opportunities to prolong and heal the lives of Black peoples they made community with. To undertake such sacred work also entails a ceaseless, ancestral relationship, as the community land-based and healing work of Harriet’s Apothecary and Soul Fire Farm evidences into the present.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for this important, forceful reconceptualization of how Black Canadian Studies can emphasize an unsettled and constantly betwixt history.

Brilliant!