Remembering Hubert Harrison, the Father of Harlem Radicalism

Hubert Harrison (April 27, 1883-December 17, 1927) was a brilliant writer, orator, educator, critic, and radical political activist. Historian Joel A. Rogers, in World’s Great Men of Color, described him as “perhaps the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time,” and civil rights and labor leader A. Philip Randolph, described him as “the father of Harlem Radicalism.” Bibliophile Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, outstanding collector of materials on people of African descent, eulogized at Harrison’s Harlem funeral that he was “ahead of his time.” As we celebrate the anniversary of Harrison’s birth, in this current political climate, it is particularly important to discuss and learn from his life and work.

Harrison was born in Estate Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies, on April 27, 1883. His mother was an immigrant worker from Barbados and his father, who had been born enslaved in St. Croix, was a plantation worker. In St. Croix, Harrison received the equivalent of a ninth-grade education, learned customs rooted in African communal traditions, interacted with immigrant and native-born working people, and grew up with an affinity for the poor and with the belief that he was the equal of any other. He also learned of the Crucian people’s rich history of direct-action mass struggles, including the successful 1848 enslaved-led emancipation victory; the 1878 island-wide “Great Fireburn” rebellion (in which women such as “Queen Mary” Thomas played prominent roles); and the general strike of October 1879.

After the death of his mother in 1899 Harrison traveled to New York as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. In his early years in New York, he attracted attention as a brilliant high school student, authored over a dozen letters that were published in the New York Times, and was involved in important African American and Afro-Caribbean working-class intellectual circles. He also did volunteer work at the White Rose Home for Colored Working Girls, and became a freethinker.

In the United States Harrison made his mark by struggling against class and racial oppression, by helping to create a rich and vibrant intellectual life among African Americans, and by working for the enlightened development of the lives of those he affectionately referred to as “the common people.” He consistently emphasized the need for working class people to develop class-consciousness; for “Negroes” to develop race consciousness, self-reliance, and self-respect; and for all those he reached to challenge white supremacy and develop an internationalist spirit and modern, scientific, critical, and independent thought as a means toward liberation.

A self-described “radical internationalist,” Harrison was extremely well-versed in history and events in Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, the Mideast, the Americas, and Europe, and he wrote and lectured indoors and out (he was a pioneering soapbox orator) on these topics. More than any other political leader of his era, he combined class-consciousness and anti-white supremacist race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism. He opposed capitalism and imperialism and maintained that white supremacy was central to capitalist rule in the United States. He emphasized that “politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea”; that “as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race” were “downright lying” and “the cant of ‘Democracy’” was “intended as dust in the eyes of white voters”; that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implied “a revolution . . . startling even to think of”; and that “capitalist imperialism which mercilessly exploits the darker races for its own financial purposes is the enemy which we must combine to fight.”

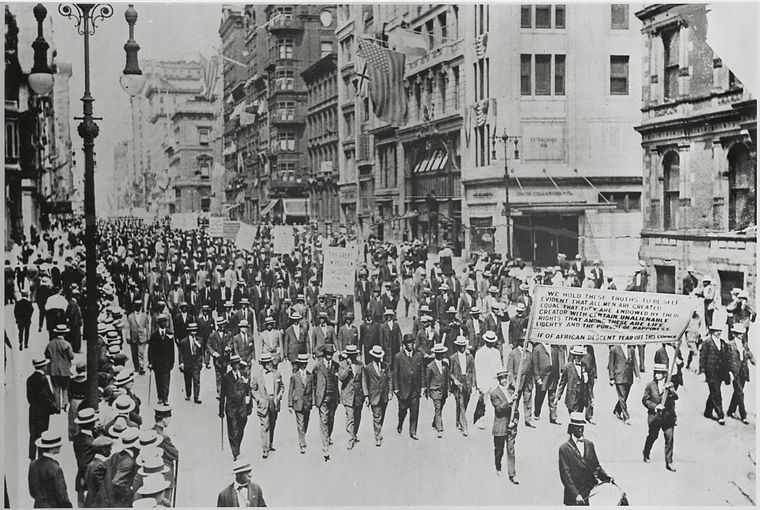

Working from this theoretical framework, he was active with a wide variety of movements and organizations and played signal roles in the development of what were, up to that time, the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) in U.S. history. His ideas on the centrality of the struggle against white supremacy anticipated the profound transformative power of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggles of the 1960s and his thoughts on “democracy in America” offer penetrating insights on struggle in America in the twenty-first century.

Harrison served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; founded the first organization (the Liberty League) and the first newspaper (“The Voice”) of the militant, World War I-era “New Negro” movement; and edited “The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort” (“intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races – especially of the Negro race”) in 1919. Harrison also wrote “When Africa Awakes: The ‘Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World'” in 1920, and served as the editor of the Negro World, making him a principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920. His views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants including the class radical Randolph and the race radical Marcus Garvey. Considered more race conscious than Randolph and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is a key link to two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement—the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X. Randolph and Garvey were important links to King marching on Washington, with Randolph at his side, and to Malcolm, whose father was a Garveyite preacher and whose mother wrote for the Negro World, speaking militantly and proudly on street corners in Harlem.

Harrison was not only a political radical, however. Rogers described him as an “Intellectual Giant and Free-Lance Educator,” whose contributions were wide-ranging, innovative, and influential. He was an immensely skilled and popular orator and educator who spoke and/or read multiple languages; a highly praised journalist, critic, and book reviewer (who reportedly started “the first regular book-review section known to Negro newspaperdom”); a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; and a bibliophile, library builder, and popularizer who was an officer on the committee that helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into what has become known as the internationally famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

In the 1920s, after leaving the Negro World, he was a pioneering lecturer for the New York City Board of Education, worked for the American Negro Labor Congress, and taught on “World Problems of Race” at the Workers School. He also wrote many articles and book reviews that appeared in the New York Times, The Nation, Amsterdam News, Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, Boston Chronicle, Modern Quarterly, his own Voice of the Negro, and other publications.

After his death at Bellevue Hospital from an appendicitis-related condition, Harrison, who lived in poverty, was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. His gravesite marker includes his image and words drawn from Andy Razaf, outstanding poet of the “New Negro Movement”—”Speaker, editor, and sage . . . What a change thy work hath wrought!” On the 138th anniversary of his birth, increased attention to the life and work of Hubert Harrison has much to offer people today.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I’ve discovered and have been following Hubert Harrison only recently, but thanks to Jeffrey Perry, I own the complete oeuvre. I appreciate deeply the diligent scholarship evidenced in each work. Harrison is one of the unknown giants in the movement. One can only wonder how many other of our warriors have gone undiscovered,

I can’t believe I’d never heard of this man. So glad to read this amazing history and discover his story. I will share with all my transplant friends living in NYC/Harlem, and other groups as well. Thank you, Jeffrey B. Perry.

I hope that many others will read about Hubert Harrison and his important work.