Remembering Cedric Robinson: Humanistic Imaginaries and the Black Radical Tradition

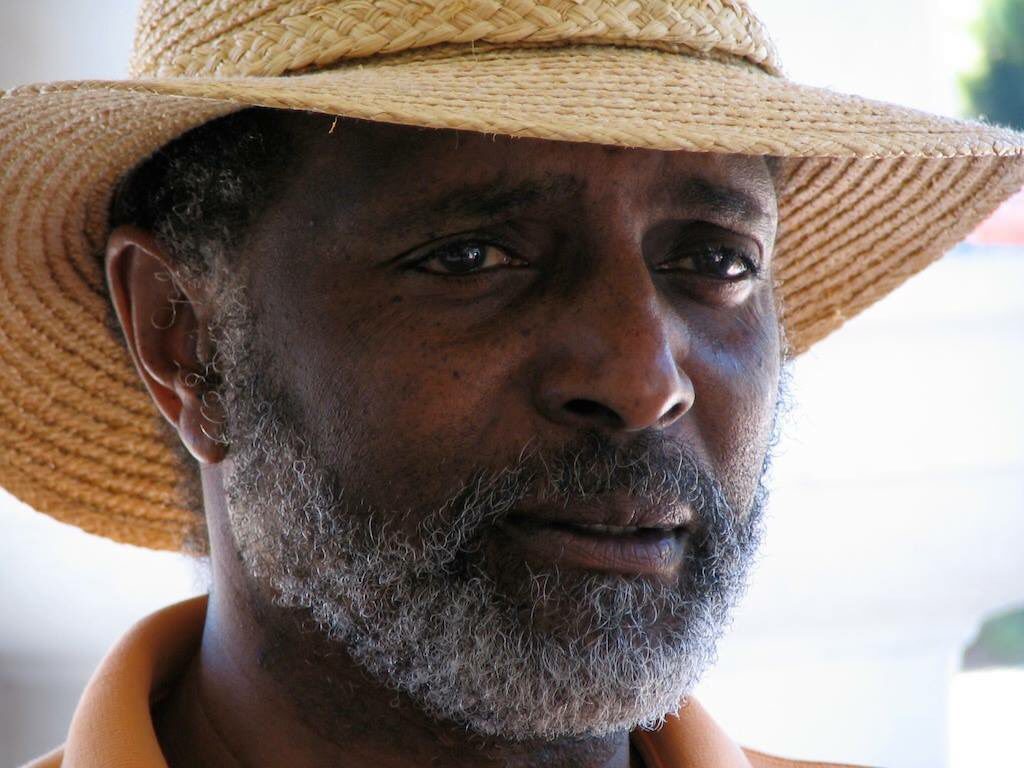

Today we continue to honor the life and legacy of Professor Cedric Robinson who passed away on Sunday, June 5, 2016. Dr. Robinson was a beloved scholar and mentor who authored several foundational texts including Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition and Terms of Order: Political Science and the Myth of Leadership and Black Movements in America. We began with reflections from Professors David J. Leonard, Josh Myers, Minkah Makalani and Cara Moyer-Duncan.

In this post, Dr. Stephen G. Hall reflects on Dr. Robinson’s unparalleled influence on African American and African Diaspora History.

***

The death of Cedric Robinson creates a deep void in the intellectual universe. Robinson’s intellectual breadth and depth was simply, in a word, astounding. Black Marxism stands as one of the foundational tomes of the African American intellectual tradition. Kaleidoscopic in scope, the book spans the breath of the black experience. It reaches across time and space, transcending the hulls of slave ships to unearth an archive of black radicalism grounded in the roots and routes of black existence in Africa and beyond. At the center of the text stands an unvarnished and unapologetic black humanity.

Like many who celebrate Robinson’s life and work, we remember him as more than an armchair academic. Rather his pursuits informed the critical intersections between practice and theory. Our ruminations are deeply personal. To meet and know him was a life-altering experience. He stood as an example of a deeply humane scholar. His insights about the black experience shaped our engagements with the complex and torturous relationship between blackness and modernity.

I met Cedric Robinson in the Summer of 1990. I had just graduated from Morgan State University, an HBCU in Baltimore, Maryland. I participated in a Summer Term External Credit program at St Hugh’s College, Oxford in Oxford, England. Organized by the philosopher Leonard Harris, the seminar featured courses on the African Diaspora taught from different perspectives. A plethora of American and British scholars filled the roster: Leonard Harris, Manthia Diawara, David Dabydeen, Sue Houchins, Marcyliena Morgan, Charlotte Pierce and Houston Baker, Dennis Brutus, David Theo Goldberg and Cedric Robinson. Robinson stood heads and shoulders above the rest. He was an imposing scholar– extremely dignified but with a proletarian sensibility about him. Erudite yet accessible, stern yet friendly and completely conversant with the long arc of historical understanding. His course on the black radical tradition illuminated the vistas of my mind. The reading list consisted of Black Marxism, which Zed Press had let slip out of publication, so we read copies (this was ten years before UNC reprinted the book with its stellar introduction by Robin Kelley) and CLR James’ Black Jacobins.

While I was familiar with The Black Jacobins, Black Marxism was a totally undiscovered country. Going to the intellectual territory covered by the book proved rough and arduous– a task of Herculean proportions. Robinson’s work was nothing short of epic. It was the stuff of Braudelian and DuBoisian proportions. Black Marxism sketched the vistas of the longue duree carefully to trace the long term structures of class formation and ideology. Simultaneously, it mapped the contours of a black radical tradition arising in the contrapuntal crevices of modernity. These sensibilities, the Braudelian and DuBoisian, merge seamlessly in the text. Robinson’s discussion brought this framework into bold relief. A gifted lecturer and student of history, he held forth and regaled us with connections and stories about the meanings and limitations of Marxist theory or the power of the Haitian Revolution. He introduced us anew to the ways in which black thinkers, albeit mostly male, such as DuBois, James and Wright undergirded the black radical tradition. How they crafted humanistic imaginaries to decenter majoritarian narratives of black marginalization and peculiarity. We were mesmerized by his erudition and humbled by how much we did not know about ourselves and our history.

Beyond our work, Robinson supported our ideas. He often took time to talk informally with us about the pressing issues of the day ranging from the Anti-Apartheid struggle, the Black Lives Matters struggle of the 1980’s, to the rise of a Gangster Rap. Robinson’s approach mirrored that of Dennis Brutus, the South African poet, who kept the struggle against Apartheid in the forefront of our minds. Robinson believed in developing young minds and always took time to nurture us. He was deeply humane and engaging. We admired his ruggedness and his playful joviality. Never too serious but deeply reflective and engaged. These qualities came into broad relief in the combative agenda of student interpersonal relations. Swimming in a sea of Black students from Ivy League schools who constituted the overwhelming majority of students in the program that summer, we (the two students from Morgan) were fiercely proud of our HBCU roots. Robinson embraced us but tempered our youthful hubris. He encouraged us to be conversant and comfortable with all of our traditions regardless of where we were trained. We shared a common experience in our collective blackness. The summer passed and the world changed. The Soviet Union disintegrated and Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1991.

Memories of Oxford and Robinson’s erudition remained etched in my mental psyche for years. A chance meeting with Robinson at Ohio State in the early years of the 21st century, where I was on the faculty in the History Department, renewed our acquaintance. Although more than fifteen years had passed since Oxford, Robinson, older and grayer, seemed no different than earlier. He had been invited to discuss the black radical tradition. His insights, especially on David Walker were prescient. Working on my first book on black historians, of which Walker is included, I delighted in his exploration of the transnational implications of Walker’s rhetoric and his location in the longer trajectory of black radical thought. Robinson’s insights, humor and willingness to take time from his busy schedule to talk transported me back to our earlier intellectual repast at Oxford. We talked about the genealogy of my ideas on the black historical tradition. He listened intently and respectfully while prodding me to think more deeply and carefully about the work. With his unforgettable smile and laugh, and a twinkle in his eyes, we connected across time and space. I felt at home in the presence of a luminary. Ever the consummate teacher and student of history, Cedric Robinson was a scholar for the ages. He would, in Chaucerian fashion “gladly lerne and gladly teache.” He will be sorely missed.

Stephen G. Hall is Assistant Professor of History at Alcorn State University. He specializes in 19th and 20th century African American historiography, intellectual, social and cultural history as well as American history. For the past ten years, he has taught a wide variety of courses in his areas of expertise. He is the author of A Faithful Account of the Race: African American Historical Writing in Nineteenth-Century America. In addition, his scholarly work has appeared in the William and Mary Quarterly, the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography and the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. His current book project, “Global Visions: African American Historians Write About the World, 1885-1960,” explores historical writing about and activism concerning the Diaspora among African American historians. You can follow him on Twitter @historianspeaks.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.