Reconsidering Jesse Jackson: The Caricature, The Person, The Politician-Part 3

This post, written by Tim Lacy, was originally published on the Society for U.S. Intellectual History’s blog and is reprinted here with permission.

Today’s post is the third in a four-part argument about the history and significance of the Reverend Jesse Jackson, Sr., as a political activist and thinker. The first two installments are here and here. My thesis is this: A full reconsideration of the politics, ideology, and political philosophy of the 1970-2000 period must involve a new, long, and serious study of Jesse Jackson. Last week’s post looked at Jackson’s biography, with a focus on his actions in the 1960s and 1970s. Today I move on to Jackson’s national political career. This aspect of my argument will require two posts.

————————————————————-

III. The Politician, Part A – The 1980s

Jackson ran for president on the Democratic ticket in both 1984 and 1988. Walter Mondale won the nomination in 1984, eventually losing in a landslide which saw the reelection of Ronald Reagan. Jackson was competitive in 1988, when he won five Southern primaries on Super Tuesday. Michael Dukakis won that Democratic nomination, only to lose in the general to George Herbert Walker Bush.1

On the theme of caricaturing Jackson, the historical record is littered with Jackson’s faux pas, one-liners, and inspirational quotes from the 1980s, but rarely do historians probe his thinking, motivations, and deliberations with political allies.

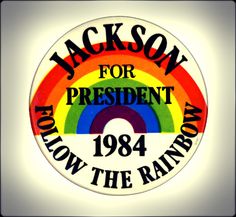

On his quotes and one-liners, in James Patterson’s Restless Giant (2005) Jackson is remembered for denigrating President Jimmy Carter’s economic record as a “domestic neutron bomb” that “doesn’t destroy bridges,” but only the politically “less organized” and those “less able to defend themselves.” A few years later, in 1984, Patterson recalls for readers that Jackson referred to New York City with an anti-Semitic slur “Hymietown.” In the late 1980s, when Jackson ran again for president as a Democrat, he branded the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) as “Democrats for the Leisure Class.” Turning toward the positive, it was at the 1998 Democratic Convention that Jackson famously declared “The American flag is red, white and blue. But America is red, white, black, brown, and yellow—all the colors of the rainbow.” In other political events he had correspondingly said the nation was “a great quilt of unity” sewn from “many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread.” 2

This language came out of Jackson’s creation, in 1984, of the National Rainbow Coalition. That organization sought equal rights for African Americans, women, and homosexuals. The Rainbow Coalition existed alongside Operation PUSH until 1996, when both merged to form the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition.3

Jackson’s political activities with the Rainbow Coalition in the 1980s have been covered once before at the USIH blog. Robert Greene’s October 19, 2014 post, titled “Towards An Intellectual History of the Rainbow Coalition,” accomplishes what its title promises.

Greene’s thesis on the Rainbow Coalition was as follows: “Jackson’s runs for president, and the broader intellectual arguments he put across during the 1980s, offered a new idea of Left-wing politics that bridged a divide between liberals who looked to the 1930s New Deal and those activists and politicians who came of age in the 1960s. For the latter, their greater concern was over cementing the gains of the Civil Rights Movement, while also fighting for women’s rights, gay rights, and a new American foreign policy geared to a post-Vietnam world.” In addition, to Greene, “discussion of the Rainbow Coalition became a referendum on the state of black politics in the 1980s.”

From Greene’s exploration we are reminded that Jackson was something of a left-wing populist in 1984. Per Paul Berman (via Greene and worth recounting), Jackson’s movement was a “‘rainbow coalition of the oppressed’ between poor white and black southern farmers.” Of course that reminds readers of the original Populists of the 1890s. With that political movement in mind, I love the quote Greene found from David Chappell: “If Jackson was a demagogue, he had the advantage of having a larger following than any of his critics—and was arguably more practical as well as more courageous, in that he dared to rally discontented masses of not just black voters but, increasingly, Hispanic, poor white, and other have-not constituencies against the popular rightward trend.” 4 Do read Greene’s post and Chappell’s book for more on Jackson’s work with the Rainbow Coalition as left-wing movement politics in the Age of Reagan.

Jackson’s cultural politics in this period have also received attention from other USIH blog regulars. He is remembered for his role in the Culture Wars on two occasions in Andrew Hartman’s recent book. For the first, which took place in 1987 (and is also recounted in my own work, Rodgers’ book, and soon in LD Burnett’s forthcoming book), involved Jackson marching with Stanford’s Black Student Union students in favor of replacing the “older” Western civilization program with a newer “Culture, Ideas, and Values” curriculum.

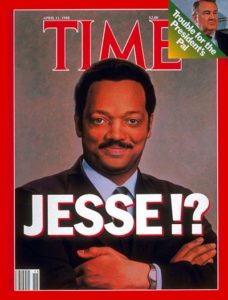

I appreciate how the “!?” on this April 11, 1988 TIME cover captures, inadvertently, the ambiguity of Jackson’s role in the Culture Wars.

Jackson famously chanted “Hey hey, ho ho, Western culture’s got to go!” and also, apparently, “Down with racism, down with Western Culture, up with diversity!” Later, in a second Culture Wars episode Jackson was, in Hartman’s retelling, foil for presidential candidate Bill Clinton’s repudiation of Sister Souljah, who Jackson had publicly supported. Clinton appeared before Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition to compare Sister Souljah to David Duke, a white supremacist.5 This event, a public rejection of extremism in one’s own party or faction, has become proverbial in political lore. In both Culture Wars episodes Jackson, in the end, remained consistent with his long-term position of defending the less powerful and disempowered. But both events pitted him against “white” conservative or normative values, diminishing his national political stature.

Of all the writings of recent intellectual historians, Jackson’s political-intellectual rhetoric received the most attention in Rodgers’ Age of Fracture. In part two of this series I noted Rodgers summation of Jackson’s race-centered Operation PUSH rhetoric, on racial parity, in the 1970s. Things became more complex as the 1970s flowed into the politics of the 1980s, and Rodgers addressed the change.

Jackson’s speeches and writings from the 1970s and 1980s were, Rodgers notes, “amalgams of pride and vulnerability…shot through with currents of moral regeneration” and “appeals to self-discipline.” This allowed him and Rainbow/PUSH to be grouped, at times, with the Nation of Islam and other black conservatives such as Shelby Steele, Glenn Loury, and Stephen Carter. Despite the Du Bois/Washingtonian (justice/self-help) tension in Jackson’s thought, he represented a voice of racial solidarity and essentialism. He was sure there was, as Rodgers recounts, a “black experience.” Jackson’s mission was to affirm diversity and a race-positive message. Quoting Jackson’s Straight from the Heart(1987), Rodgers relayed a conversation about colorblindness between Jackson and the conservative intellectual Charles Murray. Jackson said: “We don’t need to be colorblind; we need to affirm the beauty of colors and the diversity of people. I do not have to see you as some color other than what you are to affirm your person.” 6

Jackson’s speeches and writings from the 1970s and 1980s were, Rodgers notes, “amalgams of pride and vulnerability…shot through with currents of moral regeneration” and “appeals to self-discipline.” This allowed him and Rainbow/PUSH to be grouped, at times, with the Nation of Islam and other black conservatives such as Shelby Steele, Glenn Loury, and Stephen Carter. Despite the Du Bois/Washingtonian (justice/self-help) tension in Jackson’s thought, he represented a voice of racial solidarity and essentialism. He was sure there was, as Rodgers recounts, a “black experience.” Jackson’s mission was to affirm diversity and a race-positive message. Quoting Jackson’s Straight from the Heart(1987), Rodgers relayed a conversation about colorblindness between Jackson and the conservative intellectual Charles Murray. Jackson said: “We don’t need to be colorblind; we need to affirm the beauty of colors and the diversity of people. I do not have to see you as some color other than what you are to affirm your person.” 6

In Rodgers hands, Jackson is valorized as a last defender of race essentialism. Against postmodern pastiche and the mixing inherent in diversity, Jackson becomes a protector of group solidarity. Or, in Rodgers’ parlance, Jackson can never be a national leader while also leading a smaller demographic “platoon.” His defeat as a presidential candidate in the 1980s was foretold by his successful, self-defined advocacy in the 1970s for topics important to the Black American experience.

Next week I turn to the 1990s, inspired primarily Jason Stahl’s recounting of Jackson in relation to Democratic think tank maneuvering.

Tim Lacy is an educator and historian whose scholarly specialties are intellectual history, cultural history, and the history of education. He recently finished a book titled The Dream of a Democratic Culture: Mortimer J. Adler and the Great Books Idea, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2013, and is working on a second manuscript about ‘great books cosmopolitanism’ before embarking on a larger project about ignorance and anti-intellectualism. Follow him on Twitter @t_lacy.

- James T. Patterson, Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore(New York: Oxford, 2005), 171, 190, 220, 252, 367. ↩

- Patterson, 114, 190, 220; Daniel T. Rodgers, Age of Fracture (Cambridge: Belknap/Harvard Press, 2011), 114; Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American culture, Society, and Politics (New York; Simon & Schuster, 2001; reprint, Cambridge; Da Capo Press, 2002), 71. The full “hymietown” quote, reported on February 13, 1984 in The Washington Post, seems to be as follows (halfway down this page): “That’s all Hymie wants to talk about is Israel. Every time you go to Hymietown that’s all they want to talk about.” The Feb. 13 story (“Peace With American Jews Eludes Jackson,” by Rick Atkinson) is not available online, but these two (here and here) from February 22 are, and they at least affirm the derogatory slurs. The NYT picked up the slur story on 2/27/84. ↩

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Jesse Jackson”, accessed August 07, 2016. ↩

- Robert Greene, “Towards An Intellectual History of the Rainbow Coalition.” U.S. Intellectual History Blog, October 19, 2014. http://s-usih.org/2014/10/towards-an-intellectual-history-of-the-rainbow-coalition.html. Per Greene, see also: David Chappell, Waking from the Dream: The Struggle for Civil Rights in the Shadow of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Random House: New York, 2013) p. 131; “The Other Side of the Rainbow,” Paul Berman, The Nation, p. 407-410 April 7, 1984, quote on pg. 408. Robert Greene also notes the “Hymietown” incident in his piece. ↩

- Rodgers, 210; Andrew Hartman, A War for the Soul of America: A History of the Culture Wars (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 121, 228; Tim Lacy, The Dream of a Democratic Culture: Mortimer Adler and the Great Books Idea (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 198, 200; Lora D. Burnett, Canon Wars: The Stanford “Western Culture” Debates and the Neoliberal Assault on American Higher Education (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017?/forthcoming). ↩

- Rodgers, 120-21, 133. ↩