Reconsidering Black Reform Work in the Interwar Period: A Retrospective on Canaan, Dim and Far

This post is part of our online roundtable on Adam Lee Cilli’s Canaan, Dim and Far.

Panic had taken hold of me as I walked into the Fogler Library at the University of Maine. It was June 2013, and though I had just completed my third year of graduate school I was still without a well-defined dissertation topic. I knew I wanted to write about Black experiences in Pittsburgh, my hometown, but so much good work had already been done on this topic. Excellent monographs by Peter Gottlieb, Dennis Dickerson, and John Bodnar chronicled the histories of Black migrants in the Steel City and documented their engagements with the major events of the twentieth century, my period of focus. Articles by Laurence Glasco and others complimented these studies. Collectively, their painstaking efforts had resulted in a comprehensive portrait of the Black working class in the Steel City. What could I possibly contribute to this canon?

I considered this matter forlornly in the library’s study room when one of UMaine’s reference librarians approached me. He knew about my research interests and wanted to tell me that the library had just begun a temporary subscription to the digital records of the Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black weekly newspaper. The free trial ended in two weeks, so I spent the next fourteen days working feverishly to read and collect articles, features, cartoons, and editorials. My initial goal was to gather information on key events and issues in the city, but gradually I began to wonder about the people creating this information—the staff at the Courier. How did they conceive of activism and justice? In what ways did they develop alliances across class and racial lines? What linkages existed between them and middle-class Black activists involved in other racial advancement centers in the Steel City, such as the Urban League of Pittsburgh (ULP) and the Pittsburgh NAACP (PNAACP)? It turns out that we knew surprisingly little about this.

I found a gap in the literature. My predecessors produced indispensable histories of Black Pittsburgh, but these histories foregrounded working-class experiences and largely relegated Black reformers to the margins. They were not alone in this regard. Studies of interwar-era urban Black communities across the Northeast and Midwest similarly prioritized working-class issues and radical initiatives while often characterizing reformist approaches as fundamentally flawed and, in some cases, harmful. Sensing that such depictions told only part of the story, I set out to write a history that captured the dynamism of the Black reform community in Pittsburgh. The dissertation that came out of this later served as the basis for Canaan, Dim and Far.

I am grateful to Hettie Williams, Julia Bernier, James Render, and Ashley Everson for their engaging and thought-provoking reviews of my book. Collectively, they call attention to the diverse array of issues Black reformers addressed, including those related to social welfare, housing, health, civil rights, criminal justice, media representation, and labor unionism. The reviewers also took note of my effort to demonstrate the complexity of reformers. Canaan, Dim and Far is “less interested in easily categorizing Black reformers and [instead] emphasizes that the path to racial justice moves through multiple ideologies and practices,” writes Render in his review.

Engaging with the worldviews of interwar-era Black reformers prompted me to consider the nature and meaning of activism. Years ago, one of my dissertation committee members, a historian of working-class culture, suggested that the initiatives of Black reformers hardly rose to the level of activism. After all, reformers’ goals were not, on the surface, revolutionary. They did not advocate violence or call for the overthrow of capitalism, and they often used non-confrontational tactics. This was usually by design. To succeed, many of their programs and campaigns required buy-in from diverse groups of people.

The actions of Urban Leaguers in the 1920s provide an example of this. ULP staff faced an adversarial labor movement in Pittsburgh and a local government that provided few social services for the poor. Moreover, the league did not join the city welfare fund (a precursor to the United Way) until 1927, and few Black Pittsburghers had disposable income to donate to a social service organization. Gauging this situation, Urban Leaguers determined to court alliances with local employers and philanthropists by framing many of their goals in terms of community harmony and workplace reliability. Programs designed to acclimate Black migrants to the nature of industrial labor and initiatives to provide wholesome leisure outlets in inner-city neighborhoods would ultimately help migrants feel invested in Pittsburgh and loyal to their employers, they argued. This in turn would reduce labor turnover rates and save employers the expense of recruiting and training new employees. Through such sales pitches, the ULP received the financial support necessary to develop crucial social welfare programs in low-income Black neighborhoods.1 This included educational support services for under-served Black students, vocational training programs, job placement programs, home economics programs, and support for juveniles and adults in the criminal justice system. Especially vital in the 1920s were the ULP’s health campaigns, spearheaded by Black women reformers. Working together, longtime Urban Leaguer Grace Lowndes, nurse Jeannette Washington, doctor Marie Kinner, and others helped save hundreds of Black lives through their efforts to reduce infant mortality and improve overall health in the community. From 1920 to 1925, Black infant mortality in Pittsburgh declined twice as rapidly as white infant mortality.

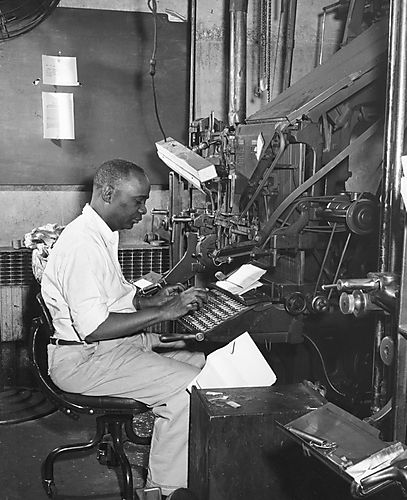

This is a shade of activism that is easily overlooked. For many of Pittsburgh’s Black reformers, “The end justified the means, which were constantly shifting and at play,” writes Julia Bernier in her review. Bernier took note of how Robert L. Vann, the longtime publisher and editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, features prominently in my book as an exemplar of the kind of pragmatism that I believe infused the Black reform tradition. Vann advocated for what he called the “liquid vote,” a notion that Black voters should be ready to change party affiliation from one election to another to best leverage their electoral power against the major parties. My chapter on the Courier’s role in the 1932 presidential election shows how this played out. Vann famously urged Black voters to switch from the “Party of Lincoln” to the Democratic party of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and he harnessed the full might of the Courier to this end. Each week from September to November 1932, the Courier’s staff—including editors, feature writers, cartoonists, and reporters—churned out story after story about the failings of the Republican Party and the merits of voting for Democrats. Behind the scenes, Vann made deals with leading Pennsylvania Democrats to ensure that significant numbers of patronage and work-relief jobs would go to African Americans. Extant records indicate that state and local Democrats honored their bargain for at least a few years after the election. Vann gained control over a number of low-level government positions, and statistics from the greater Pittsburgh area indicate high rates of Black inclusion in local work-relief projects.

Even while pursuing modest aims, Black reformers simultaneously worked toward broader, more ambitious goals—especially as political circumstances changed during the 1930s. Urban Leaguers who previously made alliances with employers and Republicans ultimately joined forces with communists, labor leaders, and Democrats during the New Deal period. As Williams and Render observed, ULP staff forcefully advocated for interracial unions by organizing labor rallies and developing programs under the auspices of its Workers’ Council. Activists in the PNAACP joined in this effort as well. Association lawyers helped prove that Pittsburgh’s schools discriminated against Black applicants for teaching positions, and PNAACP president Homer Brown used his position in the Pennsylvania legislature to author a clause in the state’s labor protection bill that effectively penalized discriminatory unions. In the process of working toward these goals, reformers forged alliances with Black radicals such as the socialist Earnest Rice McKinney and Ben Careathers of the Communist Party. Everson points this out in her review, noting that my study “focuses on the obscured connections between Black radicals and reformists during the interwar period.” Likewise, Bernier writes that “city reformers made all manner of alliances– from those with state offices and national political parties, to radical labor organizers–as circumstances warranted.”

Increasingly, reformers came to recognize that the state could serve as a powerful vehicle for civil rights when forced to do so. During World War II, the Courier’s Double V campaign placed considerable pressure on federal authorities to curtail discriminatory practices in the military. The paper published hundreds of articles, photographs, and drawings in 1942 that linked fascism abroad with racism at home. Ultimately, the campaign likely hastened federal-level decisions to open the Marines, Air Corps, and Coast Guard to African Americans, expand the role of Black servicemembers in the army and navy, and include Black women in the Women’s Corps.

My archival research for this book left me with an overall impression of a group of actors who were intellectually and ideologically prepared—prepared to forge alliances across the political spectrum, prepared to change tactics when new opportunities emerged, and prepared simultaneously to develop local social-service programs and national racial-justice campaigns. “[W]e must reject the previously more flat and one-dimensional view of the Black professional class as solely self-serving,” notes Williams in her review. Such a rejection requires a more wholistic approach to studying activism, but it can add much-needed texture to our portrait of the twentieth century freedom movement.

- The ULP’s financial records from the 1920s indicate that a significant portion of its budget came from local businesses, industrial firms, and wealthy philanthropists. ↩

I have enjoyed and learned much from these discussions of Canaan, Dim and Far. I thank each of the contributors and look forward to reading Professor Cilli’s book. Thanks again! Mark Higbee, EMU