Rebuilding the Robesonian Labor Movement

This post is an amended version of a speech delivered at the Tompkins County Workers Center’s Labor Day Picnic at Stewart Park in Ithaca, New York on September 9, 2016.

For almost 40 years the world’s ruling elites have waged a vicious class war against the masses. From one continent to the next they spread misery and poverty in the form of privatization and market reforms. They raided the public sphere. They slashed the social safety net. They gutted unions. They siphoned off a massive sum of socially generated wealth and delivered it to the super-rich.

Working people, both in the prosperous countries and in the so-called developing world, did their best to survive. They struggled to adapt, even as their lives grew less secure. In time, however, some said “Enough!” and began to fight back.

Today, that grassroots counteroffensive is reaching a decisive stage. If we glance around the planet, we find a spirit of rebellion growing among the laboring classes almost everywhere.

In South Africa, utility workers have stopped work, defying state repression and demanding a living wage. In Afghanistan, women are unionizing farm labor as a way to combat sexism and destitution. In India, millions of workers are throwing down their tools in an act of resistance against anti-labor policies.

If we consider other battlegrounds of class—the fight for autonomy in Puerto Rico and anti-austerity demonstrations in Europe—what begins to emerge are the international dimensions of modern, working-class revolt.

Here in the continental U.S., an equally extraordinary mobilization is underway. From farm laborers to retail workers to fast food employees, working people are on the march. The new militancy has generated the remarkable “Fight for 15” campaign, an effort based on the idea that all workers deserve a fair share of the incredible wealth produced by their labor.

At the same time, another class struggle is unfolding. This other worker crusade has not identified itself as a labor movement or aligned itself with most unions. Yet it has sprung from many of the social conditions that bred the “Fight for 15.” The struggle to which I’m referring goes by the name Black Lives Matter. Make no mistake—like the 20th century freedom struggle that preceded it, Black Lives Matter is a movement largely led and sustained by the black working class.

What we have in the U.S. today is two streams of grassroots insurgency: a movement against the most abusive labor practices of the new economy, especially in the service industries; and a struggle against the most toxic forms of racial violence, especially at the hands of the state. Though these crusades appear parallel, in reality they are deeply interconnected.

What we have in the U.S. today is two streams of grassroots insurgency: a movement against the most abusive labor practices of the new economy, especially in the service industries; and a struggle against the most toxic forms of racial violence, especially at the hands of the state. Though these crusades appear parallel, in reality they are deeply interconnected.

Both the Fight for 15 and Black Lives Matter are the result of sustained, local organizing. Both movements are led by the rank and file rather than by national figures. Both have engaged in direct action and other militant tactics. Both have endured political attacks by the media and the power structure. Most importantly, both arise from the systemic violence of a society that considers certain people disposable.

Recognizing the natural relationship between the two movements, some organizers have begun to fuse agendas. The Black Work Matters campaign, for example, is attempting to reveal the intersection between racist policing and the economic violence of poverty wages and precarious employment.

Yet to truly fulfill the potential for collaboration, the Fight for 15 and the broader labor movement must strengthen their commitment to anti-racism. By the same token, more Black Lives Matter activists must come to see multiracial working-class alliances as a central part of the racial justice crusade.

What is needed, in other words, is not simply a change of strategy, but a transformation of consciousness. Given the record of ethnic and racial hostility within the U.S. working class, that is a tall order, indeed. Historically, the labor movement in this country has taken great strides when it managed to overcome its most stubborn divisions and organize across racial lines. Whether we’re talking about the 1930s or the 1970s, whether we’re talking about sharecroppers or garment workers, labor struggles have been strongest when they explicitly combatted white supremacy.

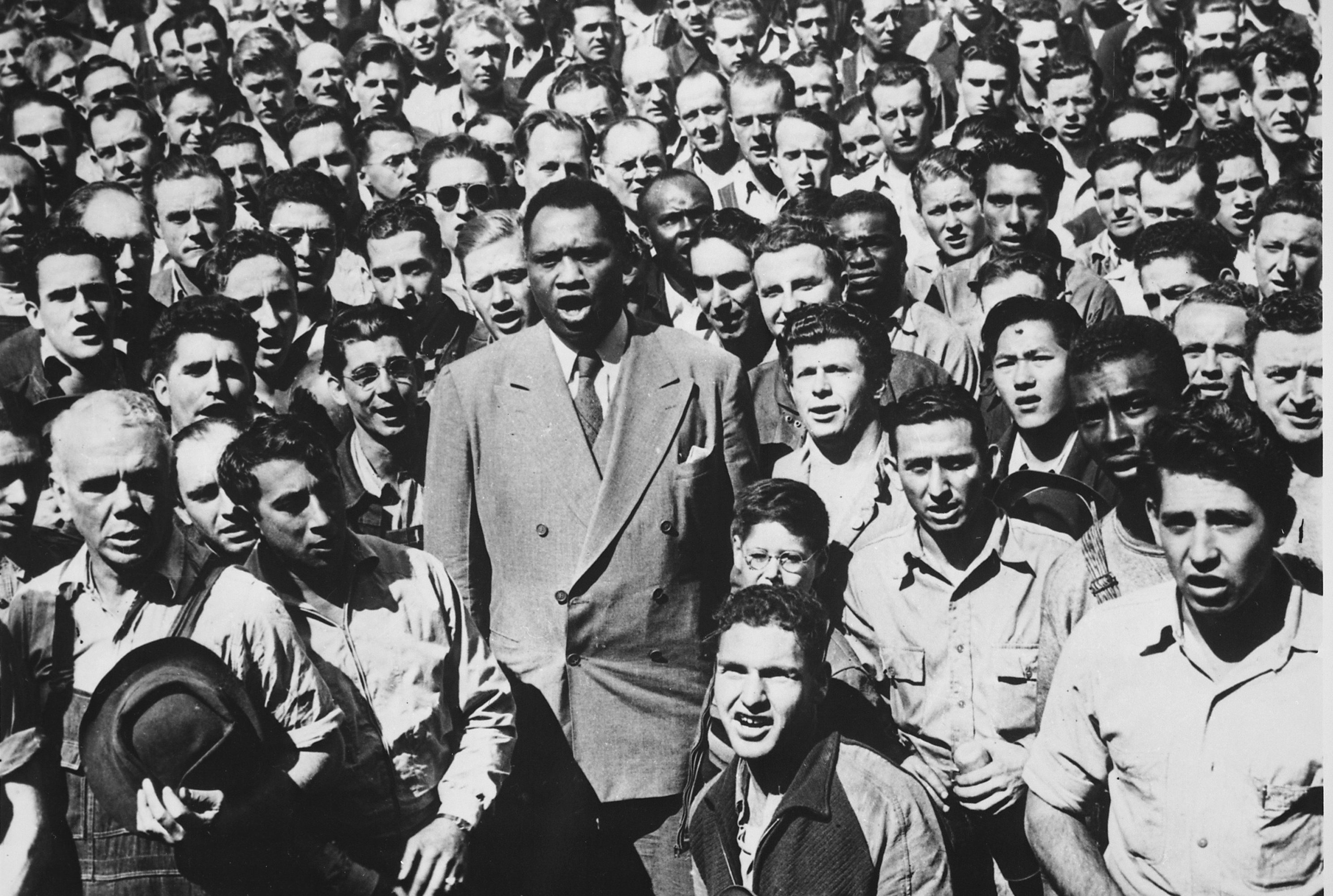

Today, when globalization has relegated so many workers to permanent insecurity, the need for broad-based alliances has never been greater. In the U.S., that means a revival of the kind of labor movement that is perhaps best embodied by the 20th century black singer, actor, and activist Paul Robeson. Robeson was a lifelong champion of working people’s struggles. But he was no friend of the conservative, Cold War labor establishment, a bureaucracy that sought incremental gains for privileged, white workers; that avoided militant confrontation with the bosses; and that offered unconditional support for American imperialism overseas. Robeson believed in the Wobbly and Communist tradition of organizing the most degraded workers. He was staunchly anti-colonialist and anti-racist, and he made common cause with movements that exemplified those ideals.

What would it mean to build a Robesonian labor movement today—a movement based on a radically democratic vision? Certainly it would mean organizing the most vulnerable workers, from retail and fast food employees to farm workers and the undocumented. It would mean acknowledging and counteracting disparities of gender and sexuality. It would mean forming alliances with popular movements for racial and environmental justice. It would mean pursuing peace, human rights, and the restructuring of the capitalist economy.

In many ways, the prospects for crafting such a movement are dim. If recent months have witnessed scores of worker rebellions, they have also seen a surge in white nationalism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, and proto-fascism. Sure, Trump’s campaign is ugly, but it is only the crudest manifestation of a deeper sickness. After all, our society revels in war and materialism. It extorts and humiliates the poor. It imprisons or otherwise discards those it refuses to properly educate, house, or employ. It scorns all life through its blind worship of profit. But it reserves special contempt and loathing for its black citizens, one or two of whom it must lynch every day and a half, simply to preserve the good order.

The anti-human logic of such a society infects each and every one of us. It is deeply embedded in our hearts and minds. Constructing a radically democratic movement is more than a solution to our labor problem. It’s a solution to our humanity problem. It’s an answer to our crises of hatred and alienation.

So what is to be done? For starters, anti-racist activists and progressive forces within the labor movement must build a popular front based on the principle of multiracial class struggle. They must create a culture of solidarity, recognizing that no worker is secure while whole classes of workers are degraded. As Karl Marx said, “Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin when in the black it is branded.”

This culture of solidarity must extend beyond national borders, for global capital never limits its destruction to any one land. Here in the belly of international finance, our movement must demand justice for Bangladeshi garment workers and for Palestinian refugees. We must combat militarism and colonial occupation abroad as part of the fight to build a peace economy at home.

On the national front, we must revive the tradition of civil rights unionism. This means launching an all-out assault on the wage gap that subjects so many women—especially women of color—to second-class citizenship. It also means choosing sides. What is a scab? It is a worker who condones the racist system of mass incarceration simply because prisons bring a few more jobs to declining towns. It is the union man who reflexively backs our “brothers and sisters in blue,” even as San Francisco cops call African Americans “cockroaches” and Oklahoma cops pepper spray an 84-year-old black woman in her home.

Building a culture of solidarity means defending the right of LGBTQ people to lead safe and dignified lives. It means resisting environmental annihilation. How can we justify the construction of a pipeline that destroys the lives and water supply of indigenous people? From North Dakota to Flint, Michigan, clean water is more precious than the privilege of those who would plunder the commons. And believe me, if they sic German Shepherds on the Indian resistance in the morning, they will sic them on the rest of us by the evening.

So let us stand with the Dakota protesters. Let us repair our hearts and minds. Let us discover the true meaning of solidarity.

Russell Rickford is an associate professor of history at Cornell University. He is the author of We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination. A specialist on the Black Radical Tradition, he teaches about social movements, black transnationalism, and African-American political culture after World War Two. Follow him on Twitter @RickfordRussell.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.