Radical Transcripts Hidden in Plain View: Excavating and Recovering “Negro Toilers” in the Communist Archive

This is the third day of the AAIHS’ roundtable on Hakim Adi’s Pan-Africanism and Communism. On the first day, we began with an introduction by Keisha N. Blain and remarks from Gwendolyn Midlo Hall. On the second day, Minkah Makalani raised questions about the archival sources on which Adi relies. In this third post, Stephen G. Hall offers an overview of the book’s interventions and emphasizes the significance of including Garveyism in the narrative and paying closer attention to women’s roles and gender relations.

***

Stephen G. Hall is Humanities Writ Large Visiting Faculty Fellow at Duke University (2014-2015) and Assistant Professor of History at Alcorn State University. He specializes in 19th and 20th century African American historiography, intellectual, social and cultural history as well as American history. For the past ten years, he has taught a wide variety of courses in his areas of expertise. He is the author of A Faithful Account of the Race: African American Historical Writing in Nineteenth-Century America. In addition, his scholarly work has appeared in the William and Mary Quarterly, the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography and the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. His current book project, “Global Visions: African American Historians Write About the World, 1885-1960,” explores historical writing about and activism concerning the Diaspora among African American historians.

***

Hakim Adi’s Pan Africanism and Communism: The Communist International, Africa and the Diaspora, 1919-1939 is an important intervention in a substantial and growing literature on the relationship between the Old Left and the African Diaspora as well as black internationalism in general.1 His recovery of radical transcripts hidden in plain view illuminates the work what Caribbean activist George Padmore termed “Negro Toilers” in the Communist archive. Challenging the oft quoted dictum that the Communist Party privileged class over race in its ideological and theoretical formations and largely neglected or marginalized the plight of black workers in its practice on the ground, Adi paints a radically different portrait. This portrait, in large part, is based on a careful excavation of newly available materials from the Archives of the Communist International in Moscow. His recovery of radical transcripts of resistance, engagement, and activism among communists of color offers fresh insights. This material sheds new light on the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), which operated as a literal clearinghouse for activist and organizational work related to interests of black workers in Europe, Africa and the Caribbean. Adi’s counter narrative to influential Caribbean activist and organizer George Padmore’s commonly accepted assertion that the Soviet Union, in an attempt to thwart Nazi designs in Europe acquiesced to her newly found imperialist allies, namely Great Britain and France, by sabotaging black workers through the committee’s abrupt disbandment in 1935. Adi’s refutes Padmore’s assertion by showing that internal and external factors led to the dissolution and then reconstitution of the ITUNCW. He uses Padmore’s framing as a window to explore the wide-ranging efforts of the Comintern and its relationship to the mobilization of black workers around the world.

Focusing on the interwar years, 1919-1939, Adi engages in a masterful project of historical recovery. In doing so, he presents this period as seminal in laying the groundwork for subsequent struggles in the public sphere for civil rights, worker’s rights, and anti-colonialism. Adi’s examination of the archival records of the Comintern yields an incredibly rich treasure trove. He casts a wide net. His view is a comprehensive one focusing on the Comintern’s engagement with black labor in the United States, Africa, the Caribbean and Europe. This work is presented through the lenses of the ITUCNW. Formed as part of the Fifth Workers Conference in 1928, the ITUCNW existence represented the culmination of Communist thinking about the role and importance of black workers and the “Negro Question.”

Perhaps, what is most suggestive to this reader is the Communist “back story” on the “Negro Question.” Rather than an opportunistic intervention against capitalist machinations, engagement with the colonial and imperialist projects appears in the private and public pronouncements of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels from the outset. Both were critical of slavery and the slave trade. They also condemned imperialism and colonialism. Marx argued for a symbiotic relationship between black and white workers. “Labour cannot emancipate itself”, wrote Marx, “in the white skin where in the black it is branded.”2 Communist opposition to the colonial project continued up through World War I. The Communist Party (CP) gained a serious foothold in Egypt and South Africa. Moreover, serious interest in the “Negro Question” informed the formation of the Third Communist International (Comintern) in 1919. The CP’s engagement with the “Negro Question” culminated in the party’s establishment in South Africa in 1921.

In terms of human capital and organizational breadth and depth, the interwar war years offered tangible opportunities for the CP to extend its influence globally. It attracted a range of human capital ranging from African Americans such as Claude McKay, James Ford, Harry Haywood, Lovett Ford- Whiteman, Williams Pickens, Williams Ferris and W.E.B. DuBois; West Indians such as CLR James, Otto Huiswoud, Hermina Huiswoud (Helen Davis), Claudia Jones, Elma Francois, Johnny Gomas, Cyril Briggs, Hubert Harrison, Hubert Critchlow, George Padmore and Africans such as Garin Kouyate, Jomo Kenyatta and Leopold Senghor and Lamine Senghor. Organizationally, Comintern conferences throughout the 1920’s became the basis for the CP’s engagement with the African Diaspora. Some of the groups on the frontline of struggle included the League Against Imperialism (LAI), the Negro Bureau of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI), the Colonial Bureau, and the Red International Labor Union (RILU), to name a few. Cyril Brigg’s African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) proved one of the most influential outgrowths of this early interest.

Beyond a plethora of black activists and organizations, intellectual and ideological engagements with the pressing questions surrounding the organization of “Negro toilers” figured prominently in the CP’s agenda. This interest manifested itself in the CP’s formulation of the Thesis on the “Negro Question” at the Fourth Congress of the Comintern in 1922. Not only did the question receive broad discussion but its conceptualization expanded beyond the domestic boundaries of the United States to the international arena. Adi points to several important ideological interventions by the Communists. Perhaps, one of the most important is the formulation of the “Black Belt” thesis. Widely attributed to Harry Haywood, perhaps the leading African American Communist of his day, Adi’s recovery of serious theoretical and practical support for the use at the highest levels of the Communist Party sheds new light on their commitment to black workers Additionally, the CP’s sponsorship of the International Congress Against Colonial Oppression and Imperialism in Brussels, Belgium in 1927 featured delegates from Africa and the African Diaspora. The passage of a comprehensive set of resolutions at the conference devoted to self-determination and self-governance further solidifies this point.

Long term interest among Communists at the theoretical and practical level on the” Negro Question” led to the establishment of the ITUCNW as part of the Sixth Congress of the Communist International in 1928. The impetus for the organization derived from a somber assessment of the realities of the labor organization for and among black workers. Some of the most important factors for the ITUNCW’s formation included racial chauvinism, the slow pace of organizational work, lack of independent unions, and recognition of the revolutionary potential of black workers. The ITUCNW’s official organ, The Negro Worker heightened the CP’s international profile. It accomplished this by focusing on the “Negro Question” in its varied manifestations in Africa, Europe, the Caribbean and the United States. Published monthly, the paper offered important information about organizing efforts as well as news and events concerning Africa and the African Diaspora.

Clearly aware of the tendency to romanticize Communist efforts among black workers, Adi presents details about the significant barriers, internal and external, to organizing workers. One of the most significant was white chauvinism, the belief among white workers and local party officials that black issues were less important. Another barrier involved the lack of concerted engagement to organize black workers stemming from an incomplete understanding of their needs and reluctance to commit adequate resources. Personal and professional rivalries and animosities were also rife in the CP leading to dissension and disagreement. Beyond internal dissension, external factors also significantly hampered organizational efforts among black workers. One of the most important and obvious of these involved the machinations of colonial powers that used the full range of surveillance and espionage efforts to disrupt attempts to organize workers in colonial territories.

After sketching out a significant history of Communist involvement black workers from an intellectual, ideological, and organizational vantage point, Adi focuses on the implications of this work on the ground. He explores the ITUNCW’s work in the European metropoles (France and Great Britain) as well as in Africa and the Caribbean, especially their organizational offshoots. These explorations provide a rich history of black labor engagement. They also illuminate the ITUCNW’s agenda in the broader world. More than simply a laundry list of contributions to black worker struggle, Adi links issues of class and race to illuminate the larger dynamics of worker organization during the interwar years. Here the idea of praxis comes into bold relief. The reader is presented with a detailed overview of how CP theory on the “Negro Question” operated when put into practice. This approach can be clearly seen in the assessment of the Comintern’s role in France and Great Britain. Throughout the period, French activists struggled to link the metropole with the colonies. The French Communist Party (PCF) attempted to address the issue of black workers through organizational channels. Despite the formation of several important advocacy groups such as the Committee for the Defense of the Negro (CDRN), the League for the Defense of the Negro (LRDN). White chauvinism, personal animosities, and internal dissension led to the implosion of the CDRN. Despite the best and worst efforts of organizers such as Garin Kouyate and George Padmore, both of whom were ultimately expelled from the party, organization of black workers in France and its colonial territories proved challenging. In Great Britain, many of the same problems existed as elsewhere in relationship to organizing black workers. Black activists in Great Britain served as the vanguard in pushing the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) to engage in significant organization of black workers The Negro Bureau of the Communist International established the Negro Welfare Association (NWA). Significant organizational efforts were also launched among seaman through the International of Seamen and Harbor Workers (ISH). Black workers participated in advocacy surrounding the infamous Scottsboro case, which was cosponsored by the International Communist Defense League (ILD), and the Communist Party of Great Britain. Moreover, British activists also took a strong anti-fascist stand through support of the Popular Front in Spain and responded aggressively to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. They also actively participated in protesting the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and publicizing the treatment of the Scottsboro boys.

In the Caribbean and Africa, the CP’s outreach efforts were often piecemeal at best. Often negotiating the contested terrain of 20th century Caribbean life with the trade union movement and violent strikes and protest actions in the British and French Caribbean, the ITUCNW worked to centralize the “Negro Question” in a Caribbean and Latin American context. Workers from these regions, however, were not represented at the Hamburg Conference in 1930. Moreover, competing organizations in the region such as the Confederacion Sindial Latinamericano (CSLA) and the Caribbean sub-Committee based in New York often diluted the ITUCNW’s ability to effectively organize workers. Elma Francois’ The Negro Welfare, Cultural and Social Association (NWCSA) proved one of the most successful organizations in the region. Although located in St. Vincent, the NWCSA ‘internationalist focus which embraced Europe, Asia and Africa. The CP relied heavily on a few organizers such as George Padmore, James Ford and Oto Huiswoud, and Helen Davis (Hermina Huiswoud) to organize the region. Curiously, there is no significant mention of C.L.R. James, one of the most significant black labor and socialist organizers of the period.3 This too, is an issue of sources and James’ Trotskyist affiliation and publication of World Revolution 1917-1936: The Rise and Fall of the Communist International (1937), a book largely critical of the Communist project. James’ influence on the region cannot be denied. In Africa, the CP organized primarily in West Africa focusing on Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Liberia and in South Africa. Wallace Johnson’s West African Youth League (WAYL) proved very effective in organizing protests against local and international injustices ranging from the Sedition Bill to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Much the same can be said of the work of Albert Nula, the leader of the African Federation of Trade Unions (AFTU) in Southern Africa.

Despite the rich archival insights Adi has uncovered, there are several notable weaknesses in the study. A certain degree of redundancy occurs in the text. This is evident in the discussions of events surrounding the establishment of the ITUNCW. Many of the details are repeated and reemphasized in different sections of the book, especially in the sections exploring activism in the European metropoles as well as the Caribbean and Africa. More compelling is the treatment of Garveyism and the gender question. More sustained attention to these issues would add an even deeper level of nuance and complexity to the text.

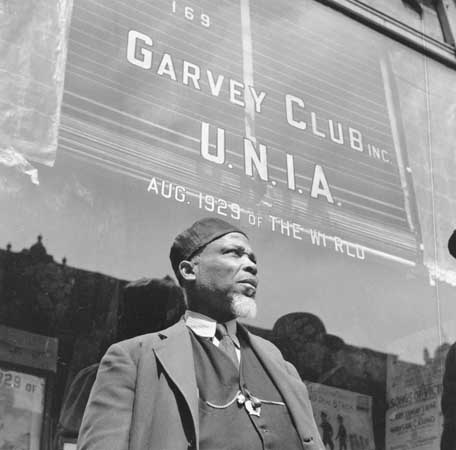

There is no sustained discussion of Garveyism either in the early twentieth century or the 1920’s. As the largest movement among African descended people, it impacted every aspect of black life in the United States, Africa, and the Caribbean during the interwar years. The discussions of the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) and Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and Otto Huiswoud and the UNIA are episodic. Communist assessments of the organization would be fruitful in terms of the thinking about worker organization and ability to promote a program of worker unity around the world. Obviously, the UNIA competed for members during the movement’s height. In what ways did the organizational approaches and tactics of the CP and UNIA intersect to challenge colonialism? While there are discussions of Garveyism in relationship to the ABB and in the Caribbean, the story seems very limited and truncated in light of the scholarly work of being produced on Garveyism and its relationship to Africa and the African Diaspora by a generation of younger scholars including Adam Ewing, Keisha N. Blain and Asia Leeds.4

Another aspect of the study which deserves more attention is the presentation of gender. Adi makes a point of arguing, in the introduction, women are essential to understanding the role of black workers. His discussion, however, is very limited in this regard. Outside of West Indian activists Hermina Huiswoud (Helen Davis), Elma Francois and South African activist Josie Mpama and a few others, the issue of gender is unexplored. In Adi’s defense, the sources have significant “gender blindness” yet more could be done to creatively flesh out this issue. Gender should not mean the piecemeal inclusion of women, but rather an exploration of how gender, masculinity and femininity inform social, political, economic, cultural, intellectual and ideological engagements in the period. The language of work has always been gendered. How did these realities play out in the Comintern, which was male-dominated? How did black workers and activists view the gendered domains of work and activism? These are important questions that deserve more sustained attention in this study.5

Despite these shortcomings, Pan Africanism and Communism is a tour de force. It offers a richly layered account of the role played by the Comintern in addressing the “Negro Question.” An excellent example of how organizational histories can reflect the intersections between the official party line and the lived experiences of activists on the ground. Here we see the intersections between a serious ideological and intellectual engagement with worker’s rights and the meanings of class, race and gender in at a crucial moment in the modern experience. These commitments fueled the work of Black activists in the CP and played a significant role in Africa and the Africa Diaspora in organizing “Negro Toilers.” Perhaps, more important, this work underscores the dynamic outpouring of contemporary scholarship on black internationalism. This work clearly demonstrates the agency and determination of black workers in the United States, Europe, Africa and the Caribbean to remake the world despite the racial chauvinism of the rank and file members of the Communist Party who appeared reluctant to do so.

- One of the most important recent studies on the relationship between the Old Left , black workers and the development of radical black internationalism is Minkah’s Malakani’s In the Cause of Freedom: Radical Black Internationalism from Harlem to London, 1917-1939. The work under review complements this excellent study. On the Old Left and African Americans, see Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radial Tradition; Robin D.G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination; William J. Maxwell, New Negro, Old Left; Bill Mullen and James Smethurst, eds., Left of the Color Line: Race, Radicalism and Twentieth Century Literature in the United States; Gerald Horne, Black Liberation/Red Scare: Ben Davis and the Communist Party; and Black Revolutionary: William Patterson and the Globalization of the African American Freedom Struggle. The complexities of black internationalism are explored in Brenda Gayle Plummer, In Search of Power: African Americans in the Era of Decolonization, 1956-1974; Nico Slate, Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India; Yuichiro Onishi, Transpacific Antiracism: Afro-Asian Solidarity in Twentieth Century Black America, Japan and Okinawa; Helen Heran Jun, Race for Citizenship: Black Orientalism and Asian Uplift from Pre-Emancipation to Neoliberal America; and Alex Lubin, Geographies of Liberation: The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary ↩

- Recent explorations of Marxism’s engagement with race, labor and the Global south include Andrew Zimmerman, Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German Empire and the Globalization of the New South; Nikki Taylor, America’s First Black Socialist: The Radical Life of Peter H. Clark; and David Roediger, Seizing Freedom: Slave Emancipation and Liberty for All ↩

- For recent work on CLR James, see Christian Hegsbjerg, C.L.R. James in Imperial Britain; C.L.R. James, Toussaint L’ Overture: The Story of the Only Successful Slave Revolt in History; A Play in Three Acts; Selwyn Cudjoe, C.L.R James: His Intellectual Legacies; Paul Buhle, C.L.R. James: The Artist as Revolutionary ↩

- Adam Ewing, The Age of Garvey: How a Jamaican Activist Created a Movement and Changed Global Black Politics; Keisha N. Blain, “ ‘For the Freedom of the Race’: Black Women and the Practices of Nationalism, 1929-1945” (PhD diss., Princeton University, 2014) and Asia Leeds., “Representations of Race: Entanglements of Power: Whiteness, Garveyism and Redemptive Geographies in Costa Rica, 1921-1950 “ (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2010) ↩

- See Adi, Pan-Africanism and Communism, xvii-xviii. For recent work on black women and the Communist Party, see Erik S. McDuffie, Sojourning for Freedom: Black Women, American Communism and the Making of Black Left Feminism; Dayo Gore, Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Woman Activists in the Cold War; Minkah Makalani, In the Cause of Freedom; and Carol Boyce Davies, Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones ↩

Harry Haywood, Negro Liberation. 1948 has a deep discussion of Garveyism, of race and class, and the need for independent Black working class leadership and liberation from white patronage.

This is an important observation. It’s incorporation in the study along with the recent outpouring of new scholarship would deeply enrich this study. Garveyism, as scholars Adam Ewing, Keisha Blain and Asia Leeds have shown, touched almost every aspect of black social political and cultural life. It served as the defining expression of black agency in the party.

Very Comprehensive

Thanks for this excellent review Stephen. I also wanted to add in the work of Ula Taylor and Natanya Duncan. Looking at those who examine Garveyism through a gendered lens would deeply enrich this discussion.

Robyn,

Thanks for the insight. Yes, Taylor and Duncan are definite inclusions.