Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century: An Interview with Jason Morgan Ward

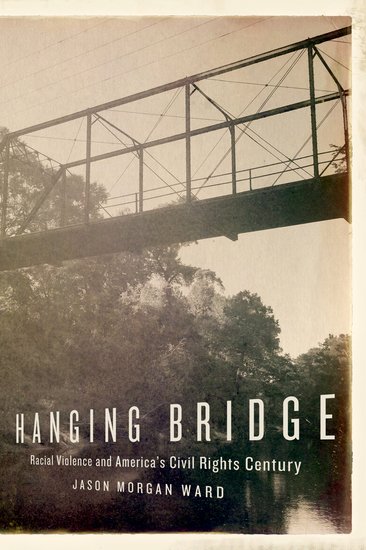

In today’s guest post, Stephen G. Hall interviews Jason Morgan Ward about his new book, Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century. Dr. Ward is an associate professor of history at Mississippi State University, where he teaches modern United States history. A native of northeastern North Carolina, he received his bachelor’s degree from Duke University and his Ph.D. in history from Yale University. Oxford University Press released his most recent book, Hanging Bridge: Racial Violence and America’s Civil Rights Century, in May 2016. In addition to recent appearances on Public Radio International and CBC Radio One, Ward presents regularly on racial violence and civil rights at academic conferences, public lectures, and book festivals across the country. During the 2013-2014 academic year, Ward completed a residential fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Humanities Forum.

His first book, Defending White Democracy: The Making of a Segregationist Movement and the Remaking of Racial Politics, was published in 2011 by UNC Press. He has published articles in the Journal of Southern History, Journal of Civil and Human Rights, and Agricultural History, and he has contributed essays to scholarly anthologies published by Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press, Louisiana State University Press, and the University Press of Florida. Ward’s commentary on race, violence, and civil rights has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and The American Historian. Named a 2016 Dean’s Eminent Scholar by the Mississippi State University College of Arts and Sciences, Ward is also an award-winning teacher and graduate advisor. Before receiving his doctorate in history, he was an elementary school teacher in Sunflower County, Mississippi. He lives in Starkville, Mississippi, with his wife and two sons.

Stephen G. Hall: Your study focuses on racial conditions in Mississippi, specifically Clarke County and the literal symbolism of the Hanging Bridge. Nan Woodruff describes the Delta as an American Congo. How are the racial histories of these areas similar and distinct?

Stephen G. Hall: Your study focuses on racial conditions in Mississippi, specifically Clarke County and the literal symbolism of the Hanging Bridge. Nan Woodruff describes the Delta as an American Congo. How are the racial histories of these areas similar and distinct?

Jason Morgan Ward: Traditionally, historians and social scientists have drawn a distinction between the Mississippi Delta and the eastern regions of the state. And these regions are different, in terms of demography and economy, and also in terms of the relative attention they have received from scholars. Given that the Delta is a black-majority, plantation region, its racial history is marked by extremes—an intense commitment to white supremacy, an enormous disparity in wealth between white and black, and—because of these extremes— of immense strategic and symbolic significance for the black freedom struggle and its adversaries.

Clarke County, which sits along the Alabama border where the northeastern Red Clay Hills meet the southeastern Piney Woods, looks quite different than the Delta and has a somewhat distinct history. That being said, regional distinctions ultimately mattered less to my story than I presumed they might. William Pickens—the NAACP official who coined the phrase “American Congo” after investigating the 1919 Elaine Massacre in the Arkansas Delta—had a strong influence on my thinking about the links between racial violence and economic repression. His analysis, which I discuss in an earlier blog post, applies well beyond the plantation districts of the Deep South.

Hall: An essential component in your story is balancing the perception of lynching and its impact on white perpetrators and black victims. How were these dynamics complicated by race, class and gender and black resistance, locally and nationally?

Ward: A big part of the regional distinctions mentioned in the previous question have to do with class. As the story goes, or went, the non-Delta regions of Mississippi are poorer and presumably “meaner” due to whites’ direct competition with African Americans for resources. But those class dynamics play out within communities and not just across regions, and in a local story you can see how whites differ significantly in their strategies for maintaining the status quo. Every town and county had its “moderate” establishment that wished to tamp down violence and avoid outside scrutiny, and these folks always liked to blame Jim Crow’s brutal excesses on bad apples and outsiders. There is no better time to see this play out than in the wake of a lynching.

Class is also important in a story full of African American outsiders who are trying to expose and make sense of racial violence and black resistance in Jim Crow Mississippi. These outsiders are typically educated, middle-class black journalists and activists, like the NAACP’s Walter White—who personally investigated the 1918 quadruple lynching—and the Chicago Defender‘s Enoch Waters—who investigated the 1942 double lynching. The Defender actually ran the headline, “Waters Finds Rural Areas Lag Behind Cities In Race Militancy,” after this trip, and Waters chided black folks in Clarke County for not fighting back and organizing protests. In his memoir, he showed much more reverence for the black southerners who kept him safe during months of investigative journalism in the rural South. I think his change of heart says as much about the role of the grassroots mobilization in the 1950s and 1960s in changing how “everyday” people are remembered in the history of the black freedom struggle. This is one of the reasons I try to highlight not only the poor and working-class locals who spearhead the movement in the 1960s, but also expressions of resistance in earlier generations when Jim Crow seemed much more monolithic and impenetrable.

Hall: The NAACP figures prominently in your story. How would you describe their role in the anti-lynching crusade throughout the long civil rights movement and how does their activism demonstrate the importance of civil rights organizations as catalysts for state and federal action on this issue?

Ward: The story of the NAACP and the story of the Hanging Bridge intersect and intertwine. The 1918 lynching occurs at an important moment—this is only the third time that future executive secretary Walter White personally investigates a southern lynching by posing as a white man. The NAACP is also gearing up for its historic May 1919 National Conference on Lynching, preceded by the publication of its report, Thirty Years of Lynching. The Hanging Bridge lynchings figure prominently in both the meeting, the report, and the antilynching campaign that builds in their wake.

By 1942, when Ernest Green and Charlie Lang are lynched at the Hanging Bridge, the NAACP is again experiencing a wartime surge and closely monitoring a simultaneous surge in mob violence. The diplomatic implications of the violence are much more central to how this atrocity is framed, from a black newspaper’s cartoon depiction of a jackbooted Nazi saluting the bridge to the NAACP’s invocation of anti-fascist rhetoric in its protest telegrams and petitions. And the New Orleans branch puts the postmortem wire photo of the boys on a recruitment flier: “They Can Not Join! But You Can!” Interestingly, as I mentioned previously, the pro-civil rights “establishment” of the Jim Crow era repeatedly chided rural black southerners in places like Clarke County for not being militant enough in response to racial violence. By the 1960s, grassroots activists in Clarke County are chiding the NAACP for not being militant enough.

Hall: Black women are an integral part of your story. How does their work broaden our understanding women’s activism and their central role in undermining lynching, poverty and oppression?

Ward: Black women played a foundational role in the anti-lynching movement, although the timing of the Hanging Bridge lynchings intersect more with the rise of the NAACP than with earlier work by Ida B. Wells and others. In the 1960s, women were the primary organizational forces behind social change in Clarke County. Without women Head Start workers providing economic leverage for boycotts and other protest actions, there was very little space in which a “movement” could emerge.

In terms of the link between lynching, poverty, and oppression, the most telling pattern I discovered in linking three generational moments of violence is that white anxieties about black economic mobility—particularly with regards to black women—permeated all three outbreaks. Put bluntly, at moments when local whites noticed that black women were leaving their kitchens for better opportunities or simply to resist exploitation, racial violence followed. This is true in 1918, when two of the four lynching victims were young black women who white officials reported had had “trouble” with a white boss who later turned up dead. Walter White discovered that both women were pregnant, likely a result of sexual exploitation at the hands of an employer they stood accused of plotting to murder. This is true in 1942, when various investigators and journalists encountered complaints about “uppity” black domestics and “Eleanor Clubs” when they inquired about the lynching of two adolescent boys. And certainly, this is true in 1966, when white officials harassed and attacked Head Start workers who had left jobs as domestics, quadrupled their income, registered to vote, and provided the muscle for a local boycott campaign by refusing to cash checks or sign supply contracts with local white merchants.

Hall: What are the legacies of the Hanging Bridge? How does it symbolize the horror of our racial past, its linkage to economic and educational deprivation, and our contemporary challenges regarding race, class and gender?

Ward: The Hanging Bridge symbolizes the power of memory and trauma to shape social struggle. Certainly, the recurrent violence that occurred there made the bridge a symbol of intimidation for anyone who might dare challenge the status quo. As a local white man bragged to a white women working undercover for the NAACP in 1942, “We just keep it for stringing up niggers.” Yet the bridge also inspired, or at least, framed resistance, from its invocation and depiction by the black press and the NAACP to young civil rights workers who described their activism as a refutation of that bridge and all it stood for.

The fact that the bridge still stands is important in a moment of memorialization. Faced with mounting public pressure and groundbreaking initiatives to remember and mark sites of racial violence, a steel-framed bridge on concrete piers has a decided advantage over other sites of violence long since reclaimed by nature or cloaked in the same legacies of obfuscation and amnesia that have obscured the Hanging Bridge for too long. One thing you cannot hide, however, is a 131-foot long river bridge.

Stephen G. Hall is the Program Coordinator of History at Alcorn State University. He is the author of A Faithful Account of the Race: African American Historical Writing in Nineteenth-Century America (UNC Press, 2009). His second book project is entitled Global Visions: African American Historians Engage the World, 1885-1960. Follow him on Twitter @historianspeaks.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.