“Racial Strife That’s Making Milwaukee Infamous”–Then and Now

Many Americans have read or seen the fiery aftermath following the recent police killing of Sylville Smith, but few are aware of the long and contentious struggle for civil rights in Milwaukee that preceded this incident. Fifty years ago, Milwaukee was also in the spotlight surrounding issues of race and violence.

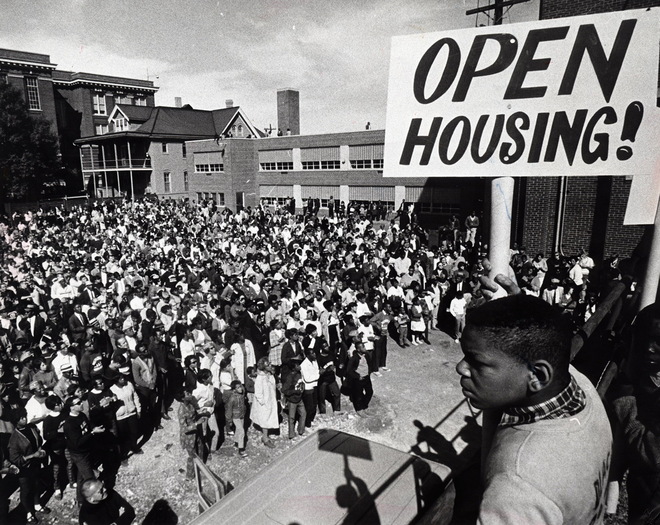

Just weeks after violence and rebellion rattled Milwaukee during the long hot summer of 1967, the city’s most dynamic civil rights organization, the NAACP Youth Council, doubled down on a direct action campaign against housing discrimination. While city leaders scrambled to assess the “how’s?” and “whys?” of the local disorder, young activists began marching to call attention to one of the most troubling issues: the intense segregation of African Americans on the city’s North Side.

2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the beginning of these open housing marches—a pivotal moment in Milwaukee’s history. Plans are underway to mark the occasion in some way, though it is much too early to know what form it will take. However, there is little doubt that the compelling stories from back then are deeply relevant now.

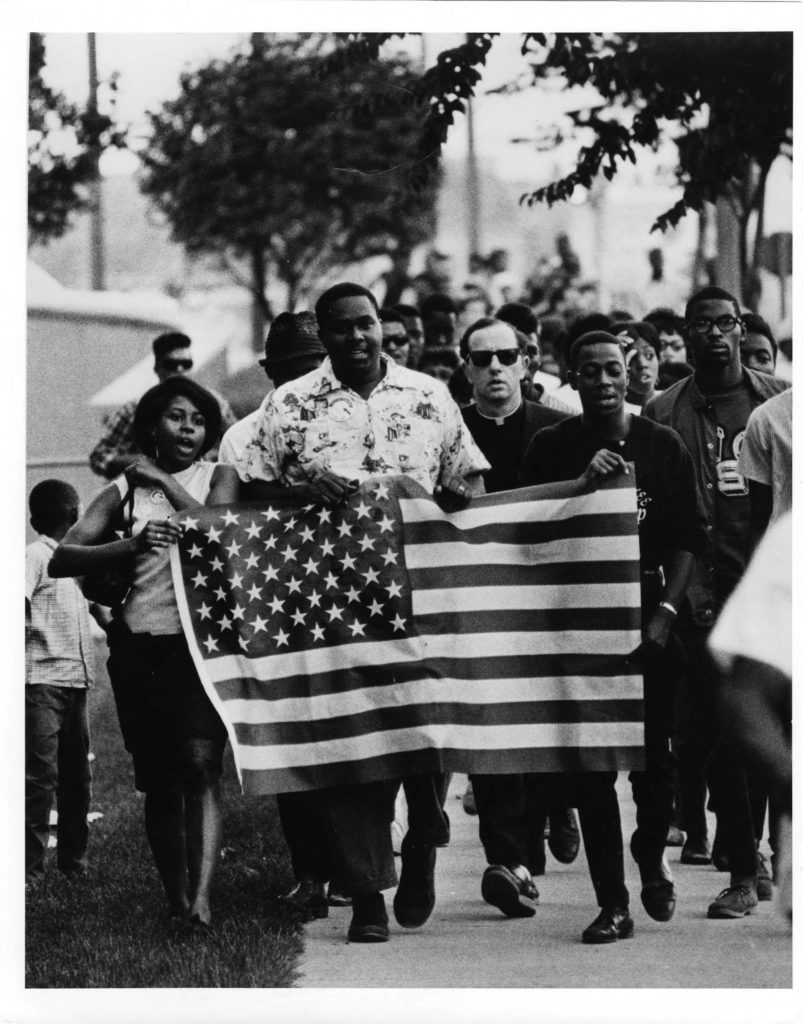

On a warm evening in late August 1967, over one hundred interracial marchers began crossing the Sixteenth Street Viaduct that connected the predominantly white, working-class South Side with the inner core to the north. Locals often joked that the viaduct was the world’s longest bridge stretching from “Africa to Poland.” Marching to a chorus of freedom songs and Black Power chants, the group’s mood darkened as they neared the far end of the bridge where massive crowds of south siders, young and old, waited with chants of their own. The counter-demonstrators waved signs–reading “White Power” and “‘I Like Niggers–Everybody Should Own A Few!!”–and hurled rocks, bags of urine, and bottles at the non-violent marchers. The Youth Council returned again the next night and faced even more protesters—upwards of 13,000—and renewed violence. Milwaukee’s police struggled to maintain order and shot teargas containers to disperse rioting whites. Marchers barely made it back to the bridge.

News photographs highlighting the dramatic confrontations made the mayhem visible for all to see. Confederate flags, racist signage, and clouds of teargas dominated the front pages of local papers, while editorials condemned both the displays of hatred and the marches as provocative. Hastily arranged reader polls and letters to the editors shared a sense of disgust while others, along with official comments from leading politicians, conveyed a sense of bewilderment and surprise.

The outburst surprised few blacks however. An editorial on September 9, 1967 in the Milwaukee Star, one of the city’s two black newspapers, noted, “What has been exhibited here this past week is nothing new to us Negroes, because we’ve known and felt these inner hatreds and prejudices long ago, but now they have been brought out into the open.” Black Milwaukee knew the visible reaction reflected the city’s deep-seated racial anxieties that reached well beyond where blacks could or could not live.

Similarly, the activists were concerned with more than just housing and sought an end to systemic forms of racism and discrimination throughout the city. Housing was a critical concern because decades of redlining and urban renewal projects pinned blacks in an urban core rife with a deteriorating housing stock and inadequate services. Housing discrimination, combined with school policies and boundaries, fostered unequal and largely segregated schools that left black schoolchildren underserved and parents frustrated.

Determined to strike a blow against the segregated schools, Milwaukee’s grassroots civil rights organizations blocked buses, challenged the construction of new schools that maintained separation, and organized school boycotts. Activists stood up to insensitive and unsupportive city leaders, led boycotts against restaurants and businesses accused of discriminatory hiring practices, and picketed local judges who were members of a local fraternal club with a “whites only” membership policy. Demonstrations against police brutality took place sporadically as an uneasy relationship with black neighborhoods simmered.

Milwaukee’s troubled racial situation mirrored that of other northern cities, yet it was the 1967 open housing marches that earned the city the moniker of the “Selma of the North.” Even Jet magazine’s catchy September 21, 1967 cover headline, “Racial Strife that’s Making Milwaukee Infamous,” was fast becoming more than a play on a local brewer’s slogan. News outlets increasingly covered the intensifying struggle between determined Youth Council activists, counter-protesters, and the police.

Milwaukee’s troubled racial situation mirrored that of other northern cities, yet it was the 1967 open housing marches that earned the city the moniker of the “Selma of the North.” Even Jet magazine’s catchy September 21, 1967 cover headline, “Racial Strife that’s Making Milwaukee Infamous,” was fast becoming more than a play on a local brewer’s slogan. News outlets increasingly covered the intensifying struggle between determined Youth Council activists, counter-protesters, and the police.

Primarily made up of African American youths, the Youth Council membership included committed whites and was advised by the outspoken Roman Catholic priest, Father James Groppi. The youths’ increasingly confrontational tactics elicited violent reactions from whites and led to altercations with police. First established in 1966, the Youth Council’s Commandos protected participants and added a degree of militancy and dynamic style to the local movement. Careful observers noted that Milwaukee’s grassroots campaign embodied perhaps one last chance for a church-based, interracial civil rights campaign, thereby countering the prevailing assumption that integrationist religious-centered efforts had run their course.

The open housing protests, boycotts, and marches continued for two hundred nights. City leaders, unwilling to pass an open housing ordinance banning discrimination—first submitted to the Common Council in 1962—faced increasing pressure to act and earned a tarnished civic reputation. The activists’ impact extended beyond Milwaukee, as well. As historian Patrick Jones demonstrated in his book about the civil rights insurgency that unfolded in Milwaukee, the open housing demonstrations caught the attention of national politicians debating civil rights legislation, ultimately impacting passage of the fair housing protections in the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Anniversaries of civil rights milestones–like the anniversary of the 1967 open housing protests in Milwaukee–provide remarkable opportunities to celebrate and recognize the struggles, sacrifices, and contributions of everyday citizens toward racial justice. Commemorating difficult events, with contested meanings and outcomes, represent opportunities to advance understanding and reconciliation, as well.

But, anniversaries and commemorations can be tricky, especially in light of the precarious state of black life in Milwaukee. The challenges ahead in celebrating became achingly clear on Sunday, August 14, the morning after violence erupted in Milwaukee’s Sherman Park neighborhood. The police shooting of Syville Smith set off two nights of violence. Six buildings were destroyed by fire. News of the shooting was quickly amplified as part of an ongoing national conversation about police violence, profiling, and mass incarceration. Intense segregation, high unemployment, and poverty are just a few of the measures that make Milwaukee one of the worst places in the nation for black people. Given these realities, few should be surprised by the fury.

If decades of history has taught us anything from Watts and Harlem to Ferguson and Baltimore and now Milwaukee, we know that no single shooting, rumor, or event is to blame for violence. These are, instead, tragic sparks that ignite tinderboxes full of longstanding forms of inequality. We know that no single protest, or act of violence, will suffice alone. It will take real work to reverse decades’ worth of pain and injustice. We need to better understand and learn from the city’s racial past in order to help heal wounds, reconcile, and move Milwaukee and all of its peoples forward. As historians, educators, and community members, this is our charge, our opportunity, and our responsibility.

Mark Speltz is the author of North of Dixie: Civil Rights Photography Beyond the South (J. Paul Getty Museum, November 2016). Follow him on Twitter at @mespeltz.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I’ve always loved the work of Father James Groppi. Thank you for sharing this article.