Race Pride, National Identity, and Jamaican Athletics

As a child growing up in Jamaica, going to the movies was a moment of national pride–not because of the symbolic power of movie theaters, but because of what happens before the film begins. We salute our nation by singing (or listening to) the national anthem and take in the brief civic lesson on what it means to be Jamaican. We feel the same pride watching our athletes perform.

This sense of national pride deflated after reading Orlando Patterson’s recent article, “The Secret of Jamaica’s Runners,” published within days of the Rio Olympics. In this article, Patterson makes the argument that the British introduced and institutionalized athletics and athletic competition to Jamaica. Although Patterson set out to offer insight into the role of institutional culture in promoting Jamaican athletic prowess, the article inadequately contextualizes how American benevolence and British institutions shaped sports development, relegating Jamaicans to a passive role in the island’s athletic evolution. It was as if Jamaicans themselves had little to do with their own athletic success. This could not be further from the truth.

The British introduced sports, not just athletics (sporting activities such as track and field), to Jamaica and its other colonies in the late 19th century in an attempt to demarcate the blurring lines between the races and classes. With its clearly defined rules and regulations that standardized how players played, dressed, and conducted themselves, organized sports imported from Britain, in CLR James’s formulation, drew ‘boundaries’ around civilized, rational amusements. Elite commentators scoffed at the amorphous, free style games of the colonized as simplistic theatrics that lacked athleticism.

Seeking to challenge their exclusion as well as prove their equal if not superior athleticism, lower class, black and brown Jamaicans partook of British cultural pastimes from highly organized and costly sports–like cricket, polo, equestrian, and golf–to inexpensive, individual sports like boxing and track and field. From the makeshift bat and ball street players–who elites denigrated as ‘young idlers’ and police arrested–emerged cricketers like J.K. Holt of Lucas who dominated cricket in the early 20th century. Unlike cricket, track and field did not require expensive equipment or the approval of a whites-only team. The Jamaican masses flocked to athletics as a way of contesting the black uncivilized/white civilized myth.

The institutional answer to Jamaica’s athletic culture that Patterson stresses, runs deeper than the British merely introducing sports and promoting competition among colonized youths. Through sports, the Jamaican ruling elite absorbed British values, beliefs, and social practices that emboldened colonial rule. The late nineteenth century concept of ‘muscular Christianity’ insisted that moral and spiritual deficiency, which white colonizers insisted were characteristic of black people, could be overcome by exercise and body discipline.

From the perspective of British colonizers, colonized people could be “disciplined” through sports. The transferable life skills that organized sports demanded of players – to obey rules and respect authority – also maintained social and racial order. Yet as churches and public schools promoted sports and competition, historians Michelle Johnson and Brian Moore explain that ‘culture wars’ erupted between colonized and colonizer who had different intentions for playing sports. Because of the praise for British and American influence embedded in Patterson’s perspective, he misses the point that sports, like other forms of culture, could be re-purposed to challenge the established social order.

Driven to prove self-worth, masculinity, and strength, Jamaican boys and girls practiced tirelessly and barefooted in the streets and yards and competed fiercely in interscholastic games. While elementary school athletics programs–such as the Inter-Secondary Schools Sports Association Boys and Girls Athletics Championship (Champs) and the Jamaica Amateur Athletics and Cycling Association meetings–showcased athletic prowess, nothing was more gratifying than being crowned ‘national champion.’

The crowning of former Jamaican Premier Norman Manley as ‘Schoolboy nation champion’ in 1912 was not a victory for Jamaicans, as up to this point and dating back to the late 1600s there were, according to historian Phillip Curtin, ‘two Jamaicas’: black/white, slave/free, colonizer/colonized. From politics and education to church and sports, Jamaica at the turn of the twentieth century remained divided by race and further stratified along class and color lines. Manley’s role in Jamaican athletics was not simply because he dominated at the 1912 Champs, or that he was a beloved founding father. Significantly, when Manley became active in politics and trade union organization in the 1930s, he seized the power of sports to unify a factious country.

For Manley, individual victories were collective victories, and he urged Jamaicans to think of Jamaica as ‘my country’ and that regardless of race, class, or color, Jamaicans were ‘my people.’ While we might debate how much Manley’s message changed the hearts and mind of Euro-Jamaicans who considered Britain home and Jamaica exile, his sporting and political triumphs and his emphasis on sports as an equalizer, unifier, and source of national pride framed the lens through which black and brown people of Jamaica viewed self and country.

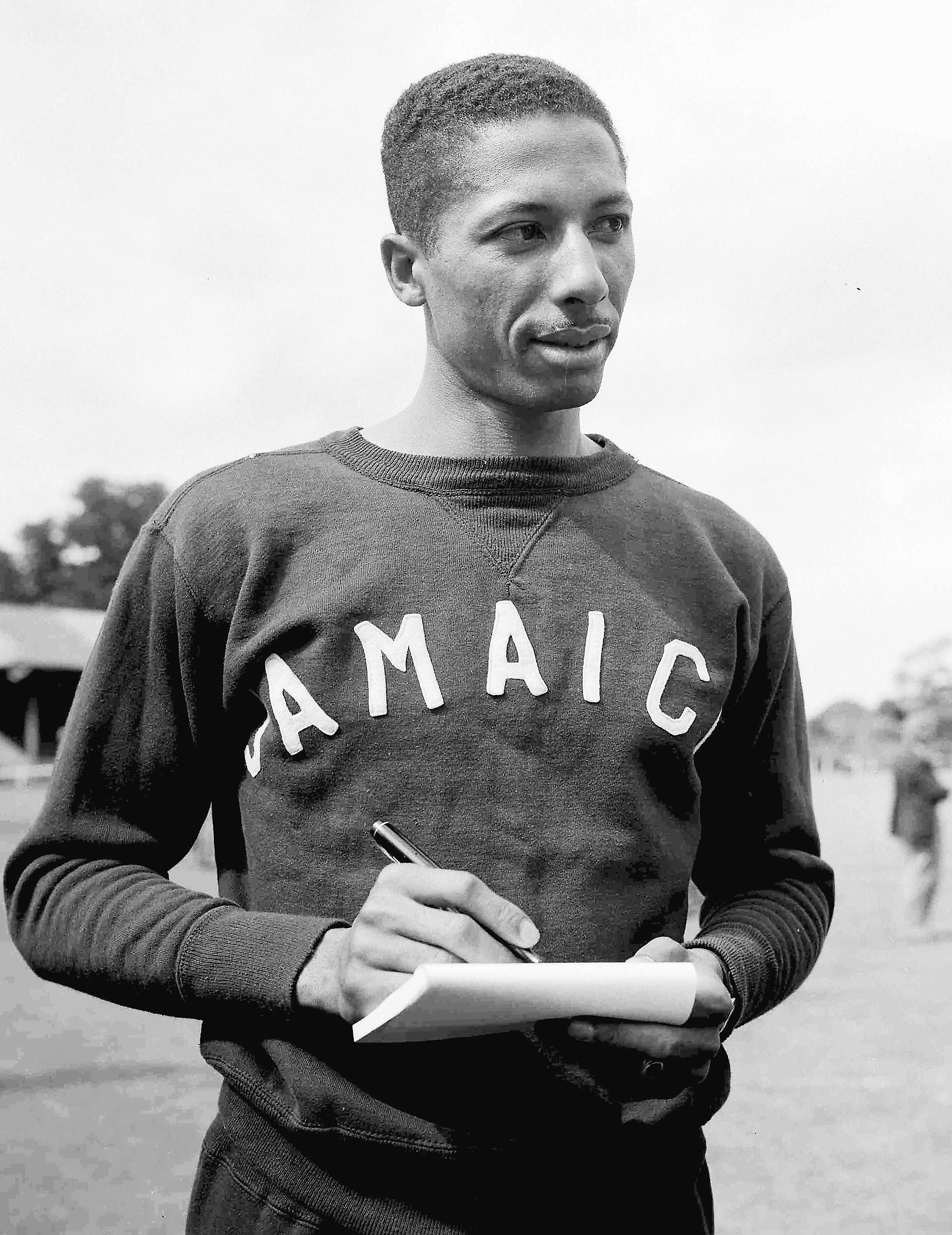

The linkage Manley made between sports and national pride took place against the backdrop of a cultural revolution in Jamaica and the extraordinary achievements of Jamaican athletes in international competition. Patterson is right that the 1940s was a pivotal era for Jamaican athletics. Herb McKenley set the world-record in the 400 meters in 1948 and in the same year, claimed silver medal at the London Olympics behind another Jamaican, Arthur Wint.

In his recent article, Patterson overly credits the American public health campaign that began in the 1920s for Jamaica’s athletic success. Undoubtedly, efforts by American institutions like the Rockefeller Foundation to control mosquitoes and to regulate fecal disposal improved the health of Jamaicans and Jamaican athletes.

However, Jamaican health practices that strengthened its athleticism resulted from a more complex struggle against imperial forces–including the United States. Rastafarians, for example, viewed American public health reforms as inseparable from white and Euro domination–which they referred to as “Babylon.” Although echoing the Euro-American reformist mantra, ‘healthy bodies, healthy minds,’ the quest for race purity that took shape in Jamaica during the 1950s rejected Babylon as corrupting the nation. In its most radical form, stripping away the vestiges of Babylon or livity meant adhering to a strict vegetarian diet or Ital, not cutting or combing one’s hair, and using leaves and herbs in places of manufactured cosmetics and tableware. Diffused to the Jamaican populace through popular music (ska, rock steady, and reggae) and the platform of the People’s National Party throughout the 1960s and 1970s–a process literary scholar Richard Burton calls the ‘Jamaicanization of Rastafarianism’—ital livity became entrenched in Jamaican identity.

Although many Jamaicans joke that athletic geniuses like Usain Bolt owe their greatness to the yam and banana staples of the Jamaican diet, the connection between Jamaica’s heavy plant-based diet, health, and athletics cannot be overlooked. Many other factors also account for Jamaica’s athletic prowess. But, there are certainly no easy answers to explain Jamaican runners’ success. It remains a mystery why Jamaican athletes have stood out from other Caribbean nations with similar demographics and overlapping histories.

However, exploring the interplay between race, athleticism, and national identity shows that Jamaican athletic dominance was not simply a matter of British and American success in reforming the minds and bodies of imperial subjects. To the contrary, Jamaican athleticism is part of a much broader and complex cultural struggle to define what it means to be Jamaican, and sheds light on the myriad strategies black people have employed to resist imperial control and domination.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Excellent piece! Brilliantly argued, a very important historical clarification that everyone involved with post colonial narratives should read. Thank you Professor Turner for this great service to the academy.

A brilliant article that captures what is truly Jamaican and partly what it means to be a Jamaican .

Thank you, Professor Turner – I thoroughly enjoyed reading this. It’s given me much to think about, as I understand the all-pervasive effect of colonial and colonizing discourse.