Private, Public, and Vigilante Violence, Part 4

This essay is Part Four of a four part series concerning the triumvirate of violence in slave societies. The first part examined private violence, the second part looked at public violence, the third at vigilante violence, and the fourth part will demonstrate how these forms of violence carried over into the Reconstruction Era and beyond.

Part IV: Reconstruction and beyond

In thinking about this triumvirate of violence—public, private, and vigilante—it becomes clear that vestiges of the slave system are still in place today. The triumvirate worked so well that after emancipation, former slaveholders employed the same tactics once again. While vigilante and private violence eventually became synonymous, all three types of violence remained interrelated as the brutality of groups like the Ku Klux Klan reinforced a particularly punitive criminal justice system. Indeed, as uniformed, professional police forces rapidly sprang up throughout the South, ties to the slave system were repeatedly revealed. As Sally Hadden wrote,

The history of police work in the South grows out of [an] early fascination, by white patrollers, with what African American slaves were doing…Their law-enforcing aspects—checking suspicious persons, limiting nighttime movement—became the duties of Southern police forces, while their lawless, violent aspects were taken up by vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan.”1

The end of slavery, however, wrought two major changes in this system of violence. First, black emancipation actually “freed” poor southern whites in several significant ways. One of the most important changes concerned the end of the imprisonment of thousands of poor southern whites, whose existence outside the slave system had threatened the antebellum social hierarchy. Before the Civil War, poor whites had functioned as social pariahs in the Deep South because they had no real place or stake in the slave system, and thus actually stood to threaten it. With emancipation, poor whites were finally granted at least enough of the privileges of whiteness to get them off the bottom rung of society, which would now be occupied by blacks. There was, in fact, a swift change in the race of the typical southern convict—overwhelmingly white during slavery, overwhelmingly black after emancipation. Similarly, vigilante violence eventually became racially-specific, too. After the first few years of Reconstruction, terroristic groups like the Ku Klux Klan stopped targeting poor whites and white Republicans and directed their ire solely at African Americans.

Second, a fundamental change occurred in the valuation of African American life. Slaveholders had always considered the enslaved as valuable property. They could beat and torture blacks at will, but they generally attempted to send their victims back to work as soon as possible. Killing the enslaved meant a substantial financial loss, so owners at least considered this fact when meting out punishments. After emancipation, however, white southerners no longer had an economic incentive to keep African Americans alive. The blatant murders of blacks, whether by employers, policemen, or Klansmen, became commonplace. No longer considered commodities, African Americans suffered the ravages of an incredibly racist, violent society. Toby Brown, who had been enslaved in South Carolina, explained this paradox: “white men lynch and burn now and the other things they couldn’t do then [under slavery]. They shoot you down like dogs now, and nothing [is] said or done.”2

As vigilante violence in the post-war period shifted from the domain of the old slave patrols, vigilance committees, and minute men organizations to newly formed groups like the Ku Klux Klan, the sheer viciousness of the white South was plainly exposed. “We have seen,” wrote W.E.B. DuBois, “city after city drunk and furious with ungovernable lust of blood; mad with murder, destroying, killing, and cursing; torturing human victims.”3

Much like the old vigilante groups, the KKK was led by the region’s elite—former slaveholders and their sons. In fact, many ex-slaves clearly recognized their old masters as Klan members during raids or attacks. Others knew their masters were involved in the violent organization through word of mouth, and a few even used this information to help save themselves from brutality. An Alabama woman reported that “Master Bennett was a Ku Klux,” while a Kentucky woman said that the KKK had recently spared her family from violence after they recognized the voice of “their young master.” Growing up in Georgia, Anderson Furr’s kin realized fairly quickly that the old slaveholders filled the ranks of the Klan. “We always thought it was our own old Master,” he stated, “all dressed up in them white robes with his face covered up, and a-talking in a strange, put-on like, voice.” Thus, while the Klan would eventually represent all classes of white southerners, its slaveholder origins must not be forgotten.4

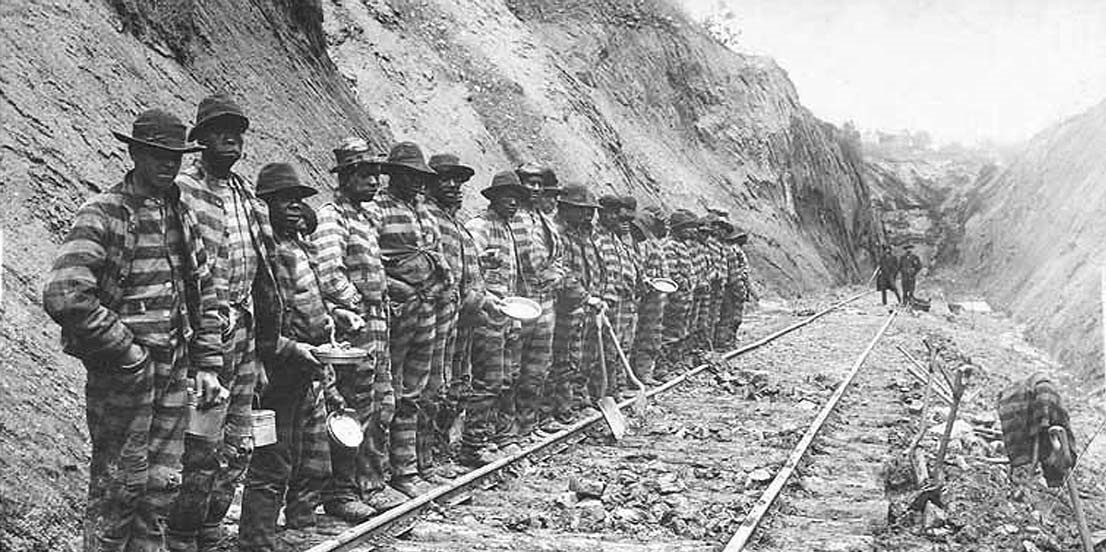

The criminal justice system, of course, became more powerful and important than ever following black emancipation; its strain of viciousness became the main tool of social and labor control. Indeed, directly coinciding with the “freedom” of African Americans, the number of people arrested in Deep South rose significantly as the substance and enforcement of the laws changed. Just as slaveholders had used several different methods to monitor and mitigate the behaviors of poor whites in the antebellum period, during the earliest years of Reconstruction, the master class and their heirs adapted these methods to gain control over African Americans. There was a critical distinction, however, concerning sentencing and punishments for white and black criminals. The consequences for blacks were much more extreme, vicious, and violent than they had been for poor whites. The post-bellum South was a chaotic, racist society for African Americans—because they now stood as the principal threats to the prevailing social and economic hierarchy.

Emancipation, therefore, did provide the theoretical framework of black freedom, and laid the groundwork for a path towards citizenship. But the Thirteenth Amendment also provided the former slaveholders with a “slavery” loophole: slavery and involuntary servitude were completely legal in conjunction with criminal convictions. Since former masters could no longer lord over enslaved African Americans, they created a path whereby the freed people could be returned to bondage. By drastically increasing the severity of criminal punishments, broadening the statutes of behavioral crimes, and effectively preventing jury service by blacks, southern whites quickly reclaimed a good deal of control over freedmen and women. The triumvirate of violence under slavery, therefore, became particularly concentrated in the criminal justice system post-slavery, where nearly anyone could become imprisoned for nearly any reason, and rogue guards and policemen could maim and kill with impunity, even before a person’s conviction. The grave excesses of this system are still acutely felt by people of color today, with one in three young African American men either incarcerated or on parole or probation. And blacks quite obviously still bear the brunt of police violence.

The current crisis of the criminal justice system is a matter worthy of moral outrage, akin to the righteous indignation of the abolitionists. The tacit acceptance of most Americans concerning the blatant, systemic racism inherent in our legal system—from search, to arrest, to charge, to council, to jury selection, to conviction, to sentence—proves that the violent legacies of the past are still painfully evident. The shackles of slavery are not so far removed. Indeed, for some Americans, the chains were never truly broken.

Thus, it is clear that the time to act is now. With the recent rise of unexplained lynchings, with the excesses and absurdities of the insatiable incarceral system, and with the hundreds and hundreds of murders by police each year, the time is now—undoubtedly and unequivocally—to reassess both our criminal justice system and the Thirteenth Amendment slavery loophole. The time is now to act upon centuries of injustice, and upon the continuing legacies of slavery. Simply put, we must help lead the charge against the sins of the present, as they are so intricately and intimately bound to the past.

- Sally Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge: Harvard, 2001), 4. ↩

- Toby Brown, in George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (Westport, CT.: Greenwood, 1972-79), Vol. 2 (SC), Pt. 1, 123. ↩

- W.E.B. DuBois, “The Souls of White Folk,” Darkwater, 1920, reprinted in Monthly Review 55, No. 6 (Nov. 2003): 47. ↩

- Steven Hahn, A Nation under our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge: Harvard, 2003), 270-1; Hannah Irwin, American Slave, Vol. 6 (AL), Part 1, 218-9; Sarah H. Locke, Ibid., Vol. 6 (IN), Part 2, 129; Anderson Furr, Ibid., Vol. 12 (GA), Part 1, 351. ↩

MY OPINION ONLY

A great article (and series) that exposes the anti-Black racist foundations of our current law enforcement and judicial system. Aligns well with recent focus on revelations about White Supremacists infiltrating the police (http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/fbi-white-supremacists-in-law-enforcement/).

It is important to note here, however, that the problem of racism against Blacks within the judicial and law enforcement systems is not limited to Whites (although Whites are by far the source and ongoing champions of such racism). Many men and women of color in law enforcement today are guilty of racism against Black (and Brown) people, especially young men, implicitly and explicitly. As evident in the September 20, 2016 fatal shooting of Keith Lamont Scott by a Black police officer, dark-pigmented skin alone can trigger life-threatening stereotypes held by white-washed police officers with the same color of skin. However, explicit expressions of racism against people of color by Black police officers is most evident in their silence about and tolerance of such racism by fellow police officers and the system at large. It is also evident in how many Black police officers voted in recent elections at Federal and State levels, supporting Donald Trump as President representing the ultimate commitment to policies and practices that support and reinforce White Supremacy within the legal systems. Then there’s the ultimate champion of White Supremacy in law enforcement: The African-American Sheriff of Milwaukee County, David Clarke (nothing else need be said about Mr. Clarke).

Much research has been done on the existence of implicit and explicit racism against people of color in law enforcement. In response, law enforcement agencies today have implemented various policies and processes to address the problem of racism against people of color. From stricter hiring policies and processes, to introduction of diversity training, law enforcement agencies are more likely responding to the pressure of public opinion and exposure of the problem, rather than doing what is necessary to identify the root causes (including the violators and perpetrators), address the root causes appropriately, and ultimately eliminate the problem. The sad reality is that, until personal and social constructs of Whiteness and White Superiority, unconscious and conscious, are identified and acknowledged as drivers of violence against and oppression of people of color by law enforcement, and until results-oriented actions are taken to eradicate, or at minimum severely punish, all behavior by law enforcement that expresses constructs of Whiteness and White Superiority, we will witness the continuation (and I fear the acceleration) of suppression, oppression, and violence committed by law enforcement (regardless of the color of their skin) against people of color, especially Black young men.