Private, Public, and Vigilante Violence in Slave Societies, Part 3

This essay is Part Three of a four part series concerning the triumvirate of violence in slave societies. The first part examined private violence, the second part looked at public violence, the third at vigilante violence, and the fourth part will demonstrate the ways in which these forms of violence carried over into the Reconstruction Era and beyond.

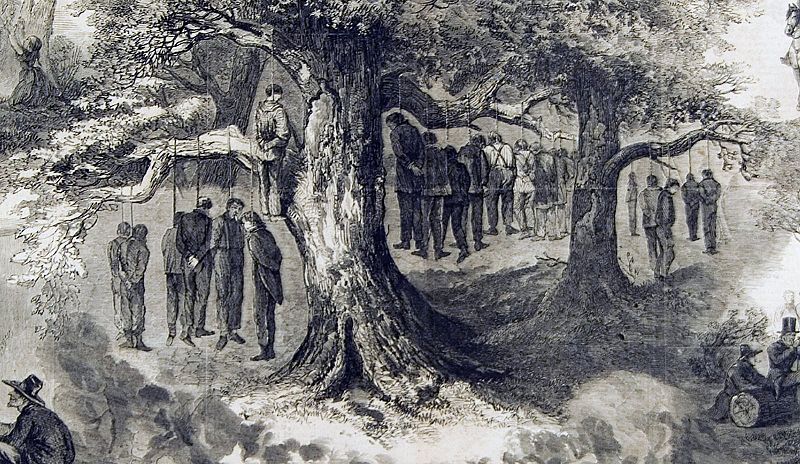

Part III: Vigilante Violence

Always working in tandem with local criminal justice systems, the Deep South’s vigilante groups were populated by the same men who ran local and state governments, comprised the slave patrols, and lorded over and brutalized the enslaved privately. While many Americans have long wondered why there were not more instances of slave rebellions, or revolts among the lower classes, the absence of these uprisings was a result of a system so complete and vicious that it prevented riots before they began. It also stopped poor whites and blacks from banding together in solidarity against the slaveholders. Indeed, the master class’ carefully crafted extra-legal code of violence allowed them to lord over a system predicated upon baseless fears, unfounded gossip, and targeted innuendo. “It was a system grown of commitments to total mastery,” one historian wrote, “and it was accepted because it terrorized to silence almost all public doubts about the peculiar institution that fathered it.” While scholars will never know exactly how many people endured the horrors of southern mobs and vigilantes, it is quite clear that the bloodshed intensified in the decade prior to the Civil War. There were at least 300 reported lynchings each year in what would become the Confederacy.1

Although slave patrols were technically part of the public, legalized system of violence, as patrols were lawfully formed and perpetuated, they uncannily resembled the vigilante violence of other groups in the Old South, as their primary goal was to instill terror and fear into the hearts of African Americans. Slave patrols were generally made up of slaveholders and landholders, and the vast majority of the rank-and-file of their membership at least had economic ties to slavery. These men sought not only to control the actions and movements of blacks—both slave and free—but also attempted to prohibit poor whites from having relationships or interactions with African Americans as well. Patrollers roamed the streets each night—brutalizing those slaves without “passes,” apprehending poor whites who were associating with blacks, and entering the homes of the enslaved to assert their power, violently whipping anyone who did not show complete, unadulterated deference.

Vigilance committees had existed in the Deep South as early as the mid-1830s, and began rapidly springing up throughout the region in the 1850s, coinciding with the rise of extra-legal minute men groups. These committees essentially monitored the behaviors and beliefs of both blacks and less affluent whites. Precursors to the Ku Klux Klan, these terroristic groups used violence and threats of violence to maintain the southern hierarchy, and their ranks proliferated as the Republican Party emerged in the North.

Of course, only the most powerful planters dominated the leadership roles. Defenders of the groups proudly claimed that the committees were filled with affluent gentlemen, “to the manor born.” Even the lowliest members, these groups often bragged, were at least slave owners. Truly impoverished whites rarely if ever became members of these brutal gangs; more often they were the victims of these bands. Though vigilance committees and minutemen groups were extralegal, they were still a cut above mob law, as the groups tended to be both more respected and more restrained. Despite these differences, however, both mob law and vigilante violence functioned similarly, with comparable means and ends. Both forms of brutality buttressed the legal system, and all of these modes of violence—private, public, and vigilante—helped maintain the social stability of the South, and prevented blacks and poor whites from coalescing, ultimately averting any uprising of the underclasses.

Violating a spate of civil liberties laws, the Deep South was a heavily censored society, where speaking of abolition, or reading about class issues, or listening to a sermon on the humanity of slaves could end in a swift death of the accused. In addition to the countless slaves who were mercilessly tortured and even murdered over even a suggestion of impropriety, it is quite clear that slaveholders used vigilante violence to prevent poor whites and blacks from banding together. In Augusta, Georgia, poor white James Cranagle was accused of “talking abolition when drunk.” He was subsequently jailed, tarred, and feathered. Just across the Savannah River in Hamburg, South Carolina, Tom Burch, an Irish-born bricklayer and plasterer, apparently used “seditious” language among slaves. The local minutemen severely whipped him, shaved half of his head, and drove him out of the state.2

A single edition of Anderson, South Carolina’s The Intelligencer referenced at least four separate instances of white men being lynched or killed for interacting with blacks. The September 11, 1860 issue very effectively warned white southerners of impending bi-racial rebellions and plots against slaveholders by a coalition of blacks and impoverished whites. In Texas, the first article stated, “A white man named Taylor, who had made negroes his only companions, had been ordered to get his traveling card immediately, or be hanged.” Several buildings had already been burned down, and there were frequent threats of entire towns being razed. This frenzied fear of revolt caused yet another “white man implicated with the negroes” to be “hung near Ione.” A second article recounted a plot to massacre slaveholders in Talladega, Alabama, apparently planned by a disaffected band of poor whites and blacks. “The concurrent testimony of the negroes examined, goes to show…that the whole plot has been concocted and set on foot by white men,” The Intelligencer crowed. “Two white men, citizens of our county…have been arrested and lodged in prison.” Yet the dictates of vigilante violence would not allow these white men—traitors to their own race, slave owners claimed—to have the right to trial, or any other procedural right of due process, for that matter. Lem Paine, one of the alleged leaders of the plotted rebellion, was soon “forcibly taken from his prison…and hung from a large China tree.” Still another article focused on a story out of Adairsville, Georgia, a small town in the Appalachian foothills. A poor white man who recently had been “discharged from the penitentiary” was detained, not by the local legal authorities, but by the town’s extra-legal vigilance committee. He “was detected in trying to instill wrong notions into the mind of a negro, who informed against him,” the paper related, and thus received from the vigilance committee “thirty-nine lashes and a half shaven head.”3

Thus, the brute force of the all-powerful slaveholders was much more intense and calculated than most historians have previously believed. As the Genoveses reminded us in 2011, “Kindness, love, and benevolence did not define paternalism.” It depended instead “on the constant threat and actuality of violence.” Dominating both the political and economic spheres, the master class maintained tight control over the vast majority of all southerners. As Richard Morris so aptly concluded, “it is impossible to ignore the extent to which arbitrary rule and even lawlessness flourished in the South, how it was fed by perverted paternalism, by the psychological unbalance of the master-servant relationship…”4

With terroristic vigilante violence, therefore, slaveholders and their allies were able to maintain control of such a potentially volatile region. Slave revolts, riots, and rebellions of the underclasses were crushed before they had a chance to get started. The old trope of docility among the southern underclasses—both black and white—is simply incorrect. There was, in fact, a burning desire for freedom and change, but the master class had devised a system so complete and so vicious that the enslaved, free blacks, and poor whites were essentially rendered powerless in the face of oppression. This total system, this triumvirate of violence, was so effective that the master class would employ it once again in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Keri Leigh Merritt is a historian of the 19th-century American South who works as an independent scholar in Atlanta. Her first book, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, will be published in 2017 by Cambridge University Press. Follow her on Twitter @kerileighmerrit.

- David Grimsted, American Mobbing, 1828-1861: Toward Civil War (New York: Oxford, 1998), 113; Russell B. Nye, Fettered Freedom: Civil Liberties and the Slavery Controversy, 1830-1860, (1963, reprint; London: Forgotten Books, 2012), 182. ↩

- Grimsted, American Mobbing, 120-1; Orville Vernon Burton, In My Father’s House Are Many Mansions: Family and Community in Edgefield, South Carolina (Chapel Hill: North Carolina, 1985), 146. ↩

- The Intelligencer (SC), Sept. 11, 1860, 4. ↩

- Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Fatal Self-Deception: Slaveholding Paternalism in the Old South (New York Cambridge, 2011), 2; Richard B. Morris, “The Measure of Bondage in the Slave States.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 41, No. 2 (Sept. 1954): 240. ↩