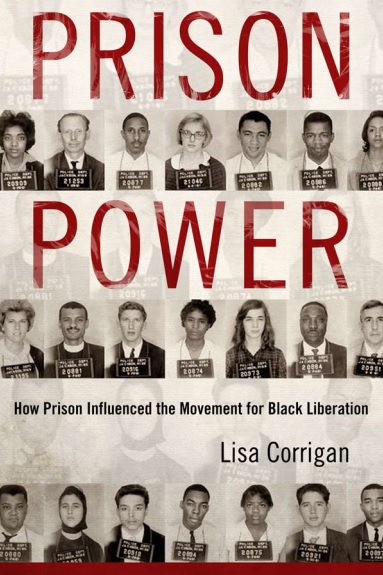

Prison Power: A New Book on the Role of Prisons in Black Liberation Struggles

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. Prison Power: How Prison Influenced the Movement for Black Liberation was recently published by the University Press of Mississippi.

***

The author of Prison Power: How Prison Influenced the Movement for Black Liberation is Lisa M. Corrigan, an Associate Professor of Communication, Director of the Gender Studies Program, and Affiliate Faculty in both African & African American Studies and Latin American Studies at the University of Arkansas. She researches and teaches in the areas of social movement studies, the Black Power and civil rights movements, prison studies, feminist studies, the Cuban Revolution, and the history of the Cold War. Her first book, Prison Power: How Prison Politics Influenced the Movement for Black Liberation (University Press of Mississippi, 2016), is the recipient of the 2017 Diamond Anniversary Book Award and the 2017 African American Communication and Culture Division Outstanding Book Award both from the National Communication Association. Her writings have also appeared in several venues, including the Quarterly Journal of Speech, the National Journal of Urban Education and Practice, and QED: A Journal in Queer Worldmaking. She co-hosts a podcast with Laura Weiderhaft called Lean Back: Critical Feminist Conversations, which was named the top podcast in Arkansas and one of the top thirty-five podcasts in the country by Paste magazine. Follow her on Twitter at @DrLisaCorrigan.

The author of Prison Power: How Prison Influenced the Movement for Black Liberation is Lisa M. Corrigan, an Associate Professor of Communication, Director of the Gender Studies Program, and Affiliate Faculty in both African & African American Studies and Latin American Studies at the University of Arkansas. She researches and teaches in the areas of social movement studies, the Black Power and civil rights movements, prison studies, feminist studies, the Cuban Revolution, and the history of the Cold War. Her first book, Prison Power: How Prison Politics Influenced the Movement for Black Liberation (University Press of Mississippi, 2016), is the recipient of the 2017 Diamond Anniversary Book Award and the 2017 African American Communication and Culture Division Outstanding Book Award both from the National Communication Association. Her writings have also appeared in several venues, including the Quarterly Journal of Speech, the National Journal of Urban Education and Practice, and QED: A Journal in Queer Worldmaking. She co-hosts a podcast with Laura Weiderhaft called Lean Back: Critical Feminist Conversations, which was named the top podcast in Arkansas and one of the top thirty-five podcasts in the country by Paste magazine. Follow her on Twitter at @DrLisaCorrigan.

In the black liberation movement, imprisonment emerged as a key rhetorical, theoretical, and media resource. Imprisoned activists developed tactics and ideology to counter white supremacy. Lisa Corrigan underscores how imprisonment—a site for both political and personal transformation—shaped movement leaders by influencing their political analysis and organizational strategies. Prison became the critical space for the transformation from civil rights to Black Power, especially as southern civil rights activists faced setbacks.

Black Power activists produced autobiographical writings, essays, and letters about and from prison beginning with the early sit-in movement. Examining the iconic prison autobiographies of H. Rap Brown, Mumia Abu-Jamal, and Assata Shakur, Corrigan conducts rhetorical analyses of these extremely popular though understudied accounts of the Black Power movement. She introduces the notion of the “Black Power vernacular” as a term for the prison memoirists’ rhetorical innovations, to explain how the movement adapted to an increasingly hostile environment in both the Johnson and Nixon administrations.

Through prison writings, these activists deployed narrative features supporting certain tenets of Black Power: pride in blackness; disavowal of nonviolence; identification with the Third World; and identity strategies focused on black masculinity. Corrigan fills gaps between Black Power historiography and prison studies by scrutinizing the rhetorical forms and strategies of the Black Power ideology that arose from prison politics. These discourses demonstrate how Black Power activism shifted its tactics to regenerate, even after the FBI sought to disrupt, discredit, and destroy the movement.

Many locate the massive expansion of the prison-industrial complex and the criminalization of black and brown communities in the policies of the Reagan administration. Lisa Corrigan’s fantastic new book turns our attention rightfully to the 1960s and offers us an incredible look at how repression of both the civil rights movement and the Black Power movement laid the groundwork for what is commonly called ‘mass incarceration’ today.–Karma R. Chávez, associate professor of Mexican American and Latino/a studies, University of Texas-Austin

Ibram X. Kendi: Did you face any challenges conceiving of, researching, writing, revising, publishing, or promoting this book?

Lisa M. Corrigan: The biggest challenge I faced with Prison Power was the resistance from (white) reviewers who were not convinced that the Black Power movement was an important historical intervention into white discourses about citizenship. Reviewers characterized Black Power leaders as “foolish, “self-centered,” “nihilistic” children, thereby performing the kind of white supremacist argumentation that Prison Power exposes and attempts to undermine.

My response was always the same: white critics could not understand Black Power as a movement, Black Power activists as interlocutors, or Black Power memoirs as legitimate subjects and objects of rhetorical and political invention because they didn’t see Black people as legible interpreters of white supremacy. While academics can give, say, Michel Foucault credit for writing about the history of the penitentiary as a disciplinary mechanism, they can’t accept that much of his information about the function of prison power came from the imprisonment of Black Power activists and political prisoners like George Jackson and Angela Davis, which speaks to the fragility of white critics in acknowledging the Black basis for white theory.

Fortunately, the University Press of Mississippi publishes criticism and theory by and about Black and brown writers and about Black and brown life in the United States and they have been overwhelmingly supportive of Prison Power in their Race, Rhetoric and Media series. Their encouragement helped the book to win the 2017 Diamond Anniversary Book Award and the African American Communication and Culture Division Outstanding Book Award for 2017, both from the National Communication Association. This was the first year in the organization’s 103-year history that a book about Black life (let alone radical Black politics) was awarded the top book award.

At every opportunity, I have been sure to discuss the institutional racism that has prevented Black authors or books about Black life from being rewarded in the humanities and have been clear that the accolades for Prison Power are possible, in part, due to my own whiteness. Nonetheless, I firmly believe that white scholars can create and circulate ethical race research by allowing Black texts to guide arguments about Black politics. I have dedicated my life to activism that highlights the importance of radical Black and brown voices and have used the success of Prison Power as a platform not just to chronicle and interpret Black Power rhetoric but also to train white readers, writers, and politicians to recognize and correct their white supremacist habits.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.