Pragmatic Black Nationalism

This is the fifth day of our roundtable on Russell Rickford’s book, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination. We began with introductory remarks by Reena Goldthree on Monday, followed by remarks by Fanon Che Wilkins, Ashley Farmer, and Ibram X. Kendi. In this post, Derrick White praises Rickford’s book for highlighting the tensions between the political imagination of Pan African nationalism and the pragmatic concerns of building a school.

Derrick E. White is currently a Visiting Associate Professor at Dartmouth College. He is the author of The Challenge of Blackness: The Institute of the Black World and Political Activism in the 1970s (University Press of Florida, 2011). He is a scholar of modern Black history, sports history, and intellectual history. He co-edited Winning While Losing: Civil Rights, the Conservative Movement, and the Presidency from Nixon to Obama (University Press of Florida, 2014) with Kenneth Osgood. He is working on two projects. The first is Blood, Sweat, and Tears: Sporting Congregations and Black College Football at Florida A. & M. University, which would be the first scholarly analysis of Black college football. It seeks to show how FAMU built a football program behind the veil of segregation, while receiving unequal material resources from the state. FAMU also serves as a node to examine the larger issues facing Black college athletics in the twentieth century. The strategies employed, and challenges faced by the Rattlers were emblematic for all HBCU football programs. The story of FAMU reveals the history of Black college football. The second project—Making a King: The King Center, Historical Power, and the Contested Terrain of Martin Luther King’s Legacy—explores the intellectual and institutional strategies the King Center used to establish King’s broad popularity and to combat oppositional interpretation. This history demonstrates that what scholars have called the “post-civil rights” era is more a product of historical power, than chronology. Dr. White has published articles in New Politics, The Journal of African American History, the C.L.R. James Journal, the Journal of African American Studies, and the Florida Historical Quarterly. He occasionally tweets @blackstar1906.

Derrick E. White is currently a Visiting Associate Professor at Dartmouth College. He is the author of The Challenge of Blackness: The Institute of the Black World and Political Activism in the 1970s (University Press of Florida, 2011). He is a scholar of modern Black history, sports history, and intellectual history. He co-edited Winning While Losing: Civil Rights, the Conservative Movement, and the Presidency from Nixon to Obama (University Press of Florida, 2014) with Kenneth Osgood. He is working on two projects. The first is Blood, Sweat, and Tears: Sporting Congregations and Black College Football at Florida A. & M. University, which would be the first scholarly analysis of Black college football. It seeks to show how FAMU built a football program behind the veil of segregation, while receiving unequal material resources from the state. FAMU also serves as a node to examine the larger issues facing Black college athletics in the twentieth century. The strategies employed, and challenges faced by the Rattlers were emblematic for all HBCU football programs. The story of FAMU reveals the history of Black college football. The second project—Making a King: The King Center, Historical Power, and the Contested Terrain of Martin Luther King’s Legacy—explores the intellectual and institutional strategies the King Center used to establish King’s broad popularity and to combat oppositional interpretation. This history demonstrates that what scholars have called the “post-civil rights” era is more a product of historical power, than chronology. Dr. White has published articles in New Politics, The Journal of African American History, the C.L.R. James Journal, the Journal of African American Studies, and the Florida Historical Quarterly. He occasionally tweets @blackstar1906.***

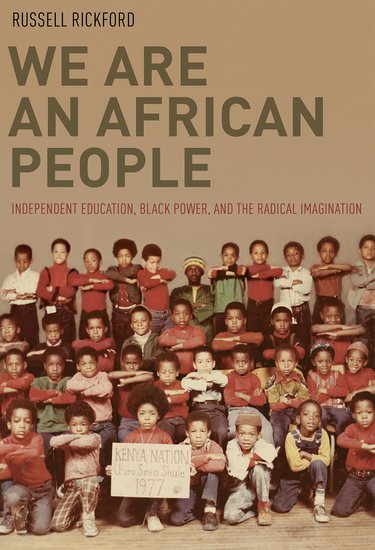

Russell Rickford’s We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination makes a significant contribution to the growing field of Black Power Studies by examining the creation of independent Pan African educational institutions that “paired separatist impulses with strains of radical internationalism and anti-imperialism.”1 The founders of these parallel, private schools attempted to concretize Black Power’s idealized goals of self-determination and Black consciousness. Rickford’s tremendously researched book identifies nearly forty schools nationwide whose curriculum was rooted in Pan African Nationalism.

We Are An African People reflects how scholars of Black Power have begun to move beyond the manifestos, charismatic leaders, and defining battles with white supremacy to pay more attention to the praxis of Black Power. Here, Rickford joins a growing number of scholars who have looked at the manifestation of Black Power on the ground over the last decade.2 His focus on what he calls “Black Power’s afterlife” especially in K-12 education is a welcomed addition to Black Power Studies.

One theme of particular note is Rickford’s attention to the tensions between the political imagination of Pan African nationalism and the pragmatic concerns of building a school. In the mid-1960s, the nexus of community control, white flight, and failing urban education led to a critical challenge against the orthodoxy of integrated schools shaped by Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Pan African activists seized on the confluence of these factors to postulate an alternative educational curriculum, initially, and later separate institutions. Rickford details how activists sought to implement the chief ideals of Black nationalist thought and ideology—self-determination and black consciousness. He shows how activists’ near universal support for self-determination and education led to the creation of independent schools in New York, Philadelphia, East Palo Alto, Jackson, Mississippi, and other locales. The hard work of institution building revealed key inconsistencies between ideology and praxis. Rickford describes how these contradictions rose to the forefront at the 1968 National Association of Afro-American Educators (NAAAE) meeting in Chicago. “‘Are we educating our children to live in a black society only,’ someone asked, ‘or are we educating for a multi-racial group society?'”3

The implementation of independent schools revealed varying interpretations of self-determination, none of which were totally cohesive. The lack of unity in Pan African independent education was exacerbated by the small numbers of students and the constant state of financial insecurity. Rickford’s analysis of these tensions is important for our understanding of Black Power. We are An African People is at its strongest when it outlines the contradictions emerging from Pan African ideology and pragmatic concerns. This book provides a valuable lesson about the contradictions that ideology can impose.

The attention to pragmatic concerns provides an additional framework to understand either the collapse of the independent schools or the right-ward shift to Afrocentric academies that have, according to Rickford, focused on narrow, mythic conceptions of Black identity and a “feeble discourse of self-help.” He broaches the pragmatic concerns facing all independent institutions in terms of funding, personnel, constituency, and accreditation deftly, paying close attention to local circumstances. For instance, readers learn that it was the East Palo Alto Nairobi Day School’s pragmatism that emerged from “the convergence of gender and class,” which allowed the institution to survive until the 1980s. This book reminds readers that despite Black Power’s idealism, it was often governed by funding.4

Still, Rickford’s apt critique of right leaning Pan African nationalism leaves us with additional questions. How is the radical imagination connected to finances? Or is the radical imagination viable when it follows what Derrick Bell calls interest convergence? 5 Are the boundaries for Pan-African independent education community control, self-esteem, and neoliberal reform? Was the decline of Black independent institutions a product of “the exhaustion of ideas” resulting from activists not “developing new, relevant political directions and practices alongside the rank and file” or as Sylvia Wynter suggests, “the systemic devalorization of racial blackness was, in itself, only a function of another more deeply rooted phenomenon”? 6 Rickford’s wonderful text pushes us as scholars and activists forward by forcing us to grapple with the pragmatic parameters of radical imagination.

- Russell Rickford, We Are An African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination, 9. ↩

- See for example: Jeanne Theoharis, Komozi Woodard, eds. Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America (NYU Press, 2005); Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt (NYU Press, 2009); Kwasi Konadu, A View from the East: Black Cultural Nationalism and Education in New York City (Syracuse University Press, 2009); David A. Goldberg and Trevor Griffey, eds. Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action, and the Construction Industry (Cornell University Press, 2010);Derrick E. White, The Challenge of Blackness: The Institute of the Black World and the Politics of the 1970s (University Press of Florida, 2011); Alondra Nelson, Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination (University of Minnesota Press 2011); Ibram X. Kendi, The Black Campus Movement and the Racial Reconstruction of Higher Education, 1965-1972 (Palgrave MacMillian 2012); Martha Biondi, The Black Revolution on Campus (University of California Press, 2012). ↩

- Rickford, We Are An African People, 59. ↩

- ibid., 249, 114. ↩

- Derrick Bell, “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma,” 93, no. 3, Harvard Law Review (January 1980): 518-533. ↩

- Sylvia Wynter, “On How We Mistook the Map for the Territory, and Re-Imprisoned Ourselves in Our Unbearable Wrongness of Being of Désêtre: Black Studies Toward the Human Project,” in Not Only The Master’s Tools: African American Studies in Theory and Practice, eds. Lewis R. Gordon and Jane Anna Gordon (Boulder: Paradigm Publishers, 2006), 115. ↩

It’s been a wonderful and educational week! Thanks very, very much!