Pittsburgh Reformers and the Black Freedom Struggle

This post is part of our online roundtable on Adam Lee Cilli’s Canaan, Dim and Far.

Historian Adam Lee Cilli’s Canaan, Dim and Far: Black Reformers and the Pursuit of Citizenship in Pittsburgh tells the overlooked history of Black reformist and radical activism in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He frames the Steel City as an urban space through which Black native Pittsburgh residents and Southern migrants alike contested their rights to citizenship in the wake of evolving physical, economic, and legal anti-Black violence. Spanning from the Progressive era until the end of World War II, this case study ultimately points to the centrality of Pittsburgh’s burgeoning Black activist community in political and civil rights activism that emerged in the urban center.

Cilli begins his study with DuBois’ 1903 The Souls of Black Folk, in which he introduced his concept of the “talented tenth.” While the mainstream literature on racial uplift and Black progressivism tends to focus on the middle class, bourgeois tendencies of organizations that adopted DuBois’ framing of the “talented tenth” as an elite group of educated Black Americans that would inevitably lead the race in its quest for uplift, Cilli urges us to consider a more nuanced understanding of their activism. Through a critical engagement with sources such as the Pittsburgh NAACP (PNAACP), Urban League Pittsburgh (ULP), and Pittsburgh Courier, he paints a rich and multilayered picture of Black reformists’ commitments to major issues plaguing the Black working class. Cilli includes personal correspondence between leading PNAACP activists such as Homer Brown, Daisy Lampkin, and others to exemplify the “social safety net” (6) that the ULP and PNAACP constructed. While it did not materialize into a revolutionary transformation of Pittsburgh’s racial landscape, Cilli asserts that it did create indisputable improvements in the daily life of Black Pittsburgh residents.

Cilli’s main argument is that historians must think past the reductionist framing of “racial uplift” activism of the 20th century as merely interested in organizing on behalf of the interests of the Black elite. While Pittsburgh’s Black middle class understood itself as a vanguard of sorts, Cilli’s study focuses on the obscured connections between Black radicals and reformists during the interwar period. Ultimately, their connection hinged on their mutual understanding that organizing outside of the parameters of the state was inevitable given the insidious nature of Jim Crow state sanctioned terror.

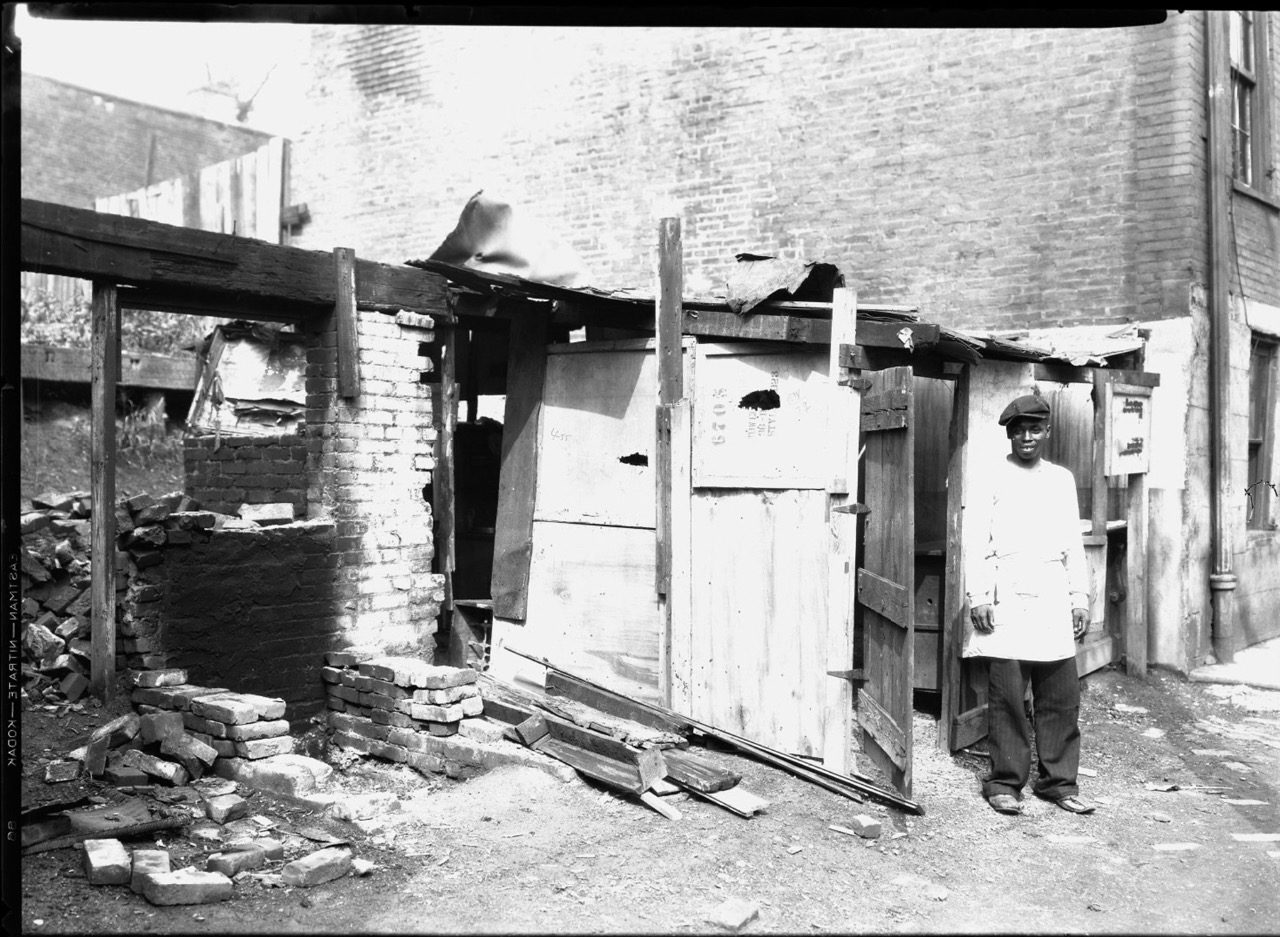

Cilli begins this analysis by tracing the origins of the reformist movement itself within the context of the Great Migration. As Black Southerners were traveling North and West in search of reprieve from Southern Klu Klux Klan vigilante violence and abysmal labor conditions, they flocked to industrial hubs, including Pittsburgh, in search of the rights promised to American citizens. By 1930, the Black population in the Steel City reached 55,000–making it the fifth largest Black community in the country (23). However, Black migrants were met with disparate access to housing and health services along with unequal employment opportunities. They found that the conditions of the South were waiting for them once they arrived in Pittsburgh.

Reformist organizations such as the ULP and PNAACP existed as a buffer between the brutal realities of Black life in Pittsburgh and a vision of citizenship that extended beyond civil rights. Cilli explains that “Reformers in the ULP secured jobs for incoming migrants….supported Black prisoners at parole hearings….[and] also lobbied employers to fund better housing and worked with migrants to improve sanitation in poor neighborhoods” (55). Cilli does not dispute the failings of reformers’ middle-class viewpoints; he urges us, however, to point our focus toward their social service initiatives of the 1920s specifically to inform our understanding of racial progress in Pittsburgh.

He expands this framing of reformist organizations in the following chapter on the legal advocacy of the PNAACP. This chapter is foregrounded with an analysis of the evolution of the criminal justice system in Pittsburgh. Cilli states that, “In Pittsburgh, the criminal justice system operated in concert with the city’s other forms of racialized social control” (85). Consequently, the NAACP fought racialized criminal injustices through established legal channels as well the court of public opinion. It took on issues of citizenship and belonging, as it fought against the unjust deportation of a group of wrongfully convicted Southern migrants. It also protested instances of racial profiling and racist representations of Black people, mainly through protesting the screening of the infamous film, Birth of a Nation. PNAACP president Homer Brown understood the importance of political leverage in waging legal war against Pittsburgh’s racist establishment. However, PNAACP officials recognized that the pursuit of legal justice alone would not suffice, as it was the very same legal system that upheld the conditions of disparity among Black citizens.

Moving into the beginnings of World War II, Cilli introduces his most salient contribution—a chronicle of the formation and impact of the Pittsburgh Courier. He states that the “Courier staff worked toward a broad vision of citizenship that included access to basic social services, public accommodations, decent housing, gainful employment, and adequate healthcare as well as civil rights” (111). Established by Robert L. Vann in 1910, the Courier became one of the most politically influential Black newspapers of the 20th century. It sought to transform the political landscape of the time through its launch of calculated campaigns in support of political leaders and ideologies that reformists and radicals alike believed would bring uplift, inclusion, and freedom to Black America.

In the wake of the Great Depression, Vann, like many Black Americans, switched his political party allegiance from the Republican to the Democratic Party. Consequently, the Courier launched a significant campaign to galvanize Black voter support for the 1932 Democratic presidential candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt. This tradition of drumming Black support for pivotal political campaigns continued well into World War II, as the Courier officially launched the national Double Victory Campaign in 1942, “historically equat[ing] fascism in Europe with Jim Crow segregation in the United States” (209). Cilli masterfully explains that the Courier served as a platform through which Black intellectuals and activists alike debated some of the most pressing issues within the Black community. This included President Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation and its exclusion of Black Americans in its federal employment and housing projects. It was within the pages of the Courier, along with other major Black periodicals, that reformists and radicals alike disputed their differing visions for a free Black race—ultimately allowing the Black American public to decide where on the political spectrum they would locate their own political ideology.

The legacy of Black reformers in Pittsburgh extended well into the Long Civil Rights Movement. Cilli’s work shows the ways in which Pittsburgh’s Black reformist institutions such as the ULP, PNAACP, and the Courier had an indispensable influence on major political, social, and economic initiatives—such as the Roosevelt presidential campaign of 1932, the Pennsylvania Civil Rights Act of 1935, and the Double Victory Movement of 1942. Through employing primary source material such as organization records, personal correspondence, periodicals, and photographs, Cilli effectively illustrates the centrality of Black Pittsburgh within the larger Black Freedom Struggle.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.