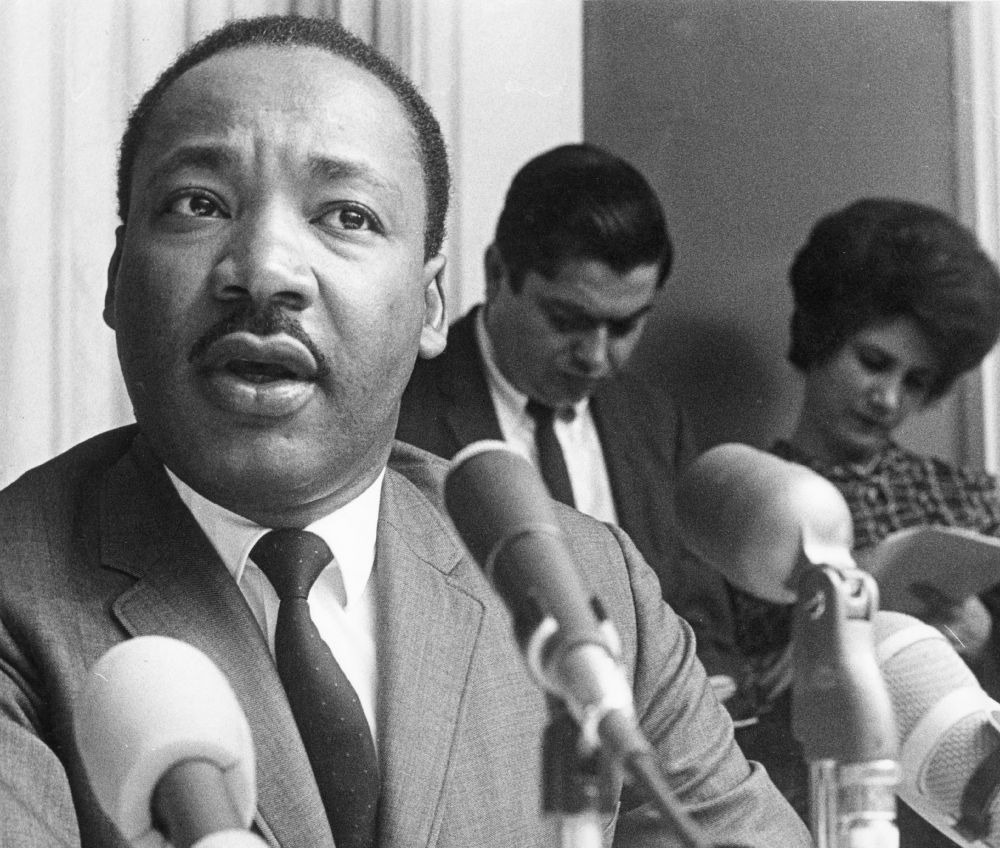

“Our Emancipation Day”: Martin Luther King Jr. in Chicago

*This post is part of our forum on Martin Luther King Jr.’s impact on American cities.

Chicago’s strategies to keep African American movement limited throughout the city have ranged from restrictive racial housing covenants to aggressive bombing campaigns that leveled the house of Jesse Binga—the first African American to own a bank—and proved itself formative in playwright Lorraine Hansberry’s early years. These strategies were always meant to preserve Chicago’s dual housing market, which Martin Luther King Jr. saw as inextricably linked to discrimination in education and employment. King’s experience in Chicago was a profound one, as he left after failing to achieve his goals. However, Chicago still left an indelible mark on the remainder of King’s short life.

The Chicago Freedom Movement, specifically the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), led by Al Raby, a Black school teacher, joined forces with Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference the summer of 1966. Between 1963 and 1964, the CCCO, comprised of nearly forty affiliate organizations—including the Chicago Catholic Interracial Council, the Chicago Urban League, CORE, the American Friends Service Committee, and friends of SNCC—organized sit-ins against overcrowded schools and massive school boycotts. At one point during these campaigns, the CCCO turned to King for assistance, and he accepted an invitation to march on Chicago’s City Hall demanding Mayor Richard J. Daly endorse integration. He arrived in Chicago in July 1965, and soon took up residence in “The Windy City” to make “a concentrated effort to create a broadly based, vibrant, nonviolent movement in the North.”

However, this wasn’t his first visit to Chicago. “Remembering Dr. King 1929-1968,” a commemorative exhibit at the Chicago History Museum documenting this time in Chicago, highlights an earlier visit in 1956, during which he delivered a sermon at Shiloh Baptist church, shortly after his house was bombed in Montgomery, Alabama. The sermon, titled “A Knock at Midnight,” called on churches to “be active in times of crisis.”

King thought that nonviolent methods must be able to address those complex economic exploitations of African Americans in the North, which had gone unaddressed for far too long. Reflecting on the explosive violence of the Watts riots in Los Angeles in August 1965, he commented, “In the South, we always had segregationists to help make issues clear…This ghetto Negro has been invisible so long and has become visible through violence.” By September of the same year, members of King’s field staff had moved into the heart of Chicago’s Near West Side to work for James Bevel, who was “fresh from Selma,” where he had been director of direct action for King. King and his family followed, moving into a tenement in North Lawndale. Commenting on his new residence, King lamented, “The slum of Lawndale was truly an island of poverty in the midst of an ocean of plenty. Chicago boasted the highest per capita income of any city in the world, but you would never believe it loooking out the windows of my apartment in the slum of Lawndale.”

According to Dr. King, “The moral force of SCLC’s nonviolent movement philosophy was needed to help eradicate a vicious system which seeks to further colonize thousands of African Americans.” He also wrote, “And I had faith that Chicago, considered one of the most segregated cities in the nation, could well become the metropolis where a meaningful nonviolent movement could arouse the conscience of this nation to deal realistically with the Northern ghetto.”

On July 10, 1966, the CCCO-SCLC organized Freedom Sunday, a rally at Chicago’s Soldier Field that was attended by nearly 30,000 people. Declaring it “our Emancipation Day,” King took the podium and said, “We are here today because we are tired, We are tired of being seared in the flames of withering injustice. We are tired of paying more for less. We are tired of living in rat-infested slums and in the Chicago Housing Authority’s cement reservations. We are tired of having to pay a median rent of $97 a month in Lawndale for four rooms, while whites in South Deering pay $73 a month for five rooms.”

These words launched a drive to make Chicago an open city for housing. The group then followed King, in 98° heat to City Hall’s LaSalle Street entrance, where King taped a list of demands to the door. The list demanded an end to police brutality and racist real-estate practices, increased African American employment, and a civilian review board for the Chicago Police Department. Richard Daley, the presiding mayor of Chicago at the time, commented, “Dr. King is very sincere in what he is trying to do. Maybe, at times, he doesn’t have all facts on the local situation. After all, he is a resident of another city. He admitted himself they have the same problems in Atlanta.”

Two days later, rioting broke out in Chicago’s Westside and 2,200 National Guard members ended the violence. Two people died. These events were discouraging to King, for Chicago was a different game altogether. Though disheartened, he remained undeterred, and in August he lead a march to real-estate office near Marquette Park on Chicago’s southwest side.

Things escalated at this march when a group of 700 whites swarmed King. Protesters also hurled bricks, bottles, and rocks, one of which hit King in the head. He noted, “I have seen many demonstrations in the South, but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today.”1

King described a similar scene at demonstration a week later in the southwest neighborhood of Ashburn, where marchers in the suburbs of Chicago were greeted by rocks, bottles, burning automobiles, and “the thunder of jeering thousands, many of them waving nazi flags. Swastikas bloomed in Chicago parks like misbegotten weeds.” Chicago’s intensity surpassed the violence that gripped Birmingham in 1963.

Later that August, CCCO-SCLC met with Mayor Daley at the Chicago Summit Agreement on housing. Seventeen hours later, the Chicago Housing Authority promised to build public housing and the Mortgage Bankers Association agreed to make mortgages available regardless of race. Activists put these policies to the test; members of the Chicago freedom movement sent teams of Black and white couples into real estate offices to see where realtors would offer the test couples homes to rent or buy. But what they found was that there was little enforcement of the Summit Agreement. King expressed his disappointment, saying, “It appears that for all intents and purposes, the public agencies have [reneged] on the agreement and have, in fact, given credence to [those] which proclaim the housing agreement a sham and a batch of false promises.”

When gains for housing and an end to police brutality proved not so easily won, King turned to Operation Breadbasket. Under the leadership of Jesse Jackson, who had move to Chicago on a Rockefeller grant to study at the Chicago Theological Seminary, Operation Breadbasket demanded that retail businesses and consumer goods industries hire African Americans while peddling goods to African Americans. Similar to the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns that sprang up in urban centers during the Great Depression, this wasn’t a new strategy. Demonstrators picketed outside of white businesses that refused to hire people of color. Eventually, twelve Operation Breadbaskets open in urban centers, which helped launch the career of Jesse Jackson in the process.

However, federal measures to secure equal housing would have to wait until after King’s assassination in 1968; only then did Congress pass the Fair Housing Act. Civil rights activists hoped that this legislation would provide Blacks equal access to and end discrimination within the housing market, but that hope seems to have gone unrealized. Fifty years later, segregation remains a defining feature of life in Chicago.

King left Chicago the start of 1967, taking time away to write the first draft of his final book Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? It recounts the lessons King learned from his tumultuous time in Chicago. These experiences confirmed that “the persistence of racism in depth and the dawning awareness that Negro demands will necessitate structural changes in society have generated a new phase of white resistance in North and South.”

Chicago entrenched King’s view that desegregation and the right to vote were essential, but that African Americans and other minorities would never enter full citizenship until they had economic security. Adequate housing, an end to police brutality, access to jobs offering decent pay, and an end to residential segregation remain essential components of this security. When honestly reflecting on his death in 2018, one must ask–how many of these components still remain out of reach in the Windy City?

- “Dr. King is Felled by Rock,” August 6, 1966, Chicago Tribune. ↩

Great article!

Great article!