On Racism and Racial Violence in the Comics

This guest post is part of our blog series on Comics, Race, and Society, edited by Julian Chambliss and Walter Greason.

Some of the most visceral images of March: Book Two take place as the Freedom Riders arrive in Montgomery, AL, on May 20, 1961, encountering a mob who viciously attack them. In these panels, Nate Powell’s black and white artwork, like his work in The Silence of Our Friends (2012), juxtaposes and plays with our general connotations of white and black. This juxtaposition becomes most apparent in the panels that show a young, white boy, at the behest of his father, joining in the assault on the Freedom Riders. In one of the panels, the father’s words, “git them eyes!” carry over into an image of the boy’s face, in front of a black background. The boy’s eyes look as if they are glowing with demonic rage as blood splotches appear on his face and his fingers reach out towards the reader, eliminating the victim, James Zwerg, from the frame. The grotesqueness of these panels recalls Reginald Marsh’s This Is Her First Lynching and Paul Cadmus’ To the Lynching! from the NAACP’s 1935 exhibit An Art Commentary on Lynching.

As part of the NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign, Walter White organized An Art Commentary on Lynching in New York in 1935 with contributions from both black and white artists in various mediums. The exhibition ran for two weeks. Jenny Woodley notes that “White wanted the audience for his exhibition to be liberaled, moneyed, northern whites . . . who would normally shy away from a subject as unpalatable as mob violence and to provoke the many apathetic whites” who became desensitized to the atrocities of lynching. Out of the thirty-eight artists who submitted works for the exhibition, there were only ten African Americans and one woman. The others, including Marsh and Cadmus, were white males.

Like Powell’s panel, Marsh’s image is in black and white, and the inhabitants of the picture appear joyous yet grotesque, enveloped in hatred. We do not see the victim of the violence in This Is Her First Lynching; instead, we see the psychological effects of racism and segregation on the perpetrators of the heinous act that occurs in the “blank space” off stage.1 I have ever seen.”] Marsh’s image shows a mob viewing a lynching, and in the middle of the crowd, a woman holds up a young girl. Unlike the other individuals in the picture, the girl appears inquisitive, as if she is learning a lesson like the boy does in March after he attacks Zwerg. She holds a finger to her chin, pondering the heinous act in the “blank space.” The woman holding the girl has a contorted smile on her face that exudes animosity and an abhorrence for the victim. Carmenita Higginbotham notes that Marsh’s image aims to confront an urban audience to the horrors of lynching, and she calls upon “us to question how the work operates and invites us to consider for whom it was intended.” Through this representation, Marsh delves into the psychological effects of oppression on the oppressors themselves. Margaret Rose Vendryes argues “Marsh’s matter-of-fact handling accentuates the macabre without overt condemnation” of the act itself. What does this removal do for a “liberaled, moneyed, northern white” audience whose exposure to lynching and mob violence may only be through newspapers and the media? How does this carry over to a work like March as well, a work that crosses time and space?

Paul Cadmus’ To the Lynching! presents another psychological effect, one of incongruous racism and bigotry that engulfs the very being of an individual and the community. Like Marsh’s This Is Her First Lynching, Cadmus’ lithograph presents the lynch mob with distorted features and visages. The man at the top left looks ghoulish, and his hand takes on the characteristics of an animal’s claw. The man’s face at the bottom appears to reverse stereotypical images of African Americans with his mouth, and the man’s hands on the right again look like claws or talons gouging at the eyes of the victim. Commenting on the framing of Cadmus’ image, Vendryes says,

To the Lynching! situates the viewer on top of the scene. We are drawn into the confusion, where the figures are disturbingly identical in color. Cadmus’s willingness to pull the viewer in so close might be a sign of his awareness that the majority of those who would visit the exhibition would be white. The triangle of white men, in their freedom, are the ones to be feared.

Cadmus’ image invokes chaos, bedlam, and violence through its swirling lines that draw the viewer’s attention to the victim in the middle of the carnage. Unlike Marsh, Cadmus displays the victim of mob violence, and like Marsh, Cadmus highlights the inescapable psychological effects of the act upon those holding the African American man down.

Through their varied depictions, Marsh and Cadmus both implicate the viewer in the act that occurs. While Marsh does not show the violence, he places the viewer in the crowd who observes the violent act off stage, and he draws the viewer’s attention to the ways that ignorance of the ongoing epidemic affects those who stand idly by doing nothing, thus associating the audience with the unseen act. Cadmus’ lithograph also draws the audience into a position of association by placing us above the scene, looking down into the swirling madness.

Powell creates the same type of grotesque, psychological imagery; however, the panels appear surrounded by images of the victims as well. During the attack, the faces of the mob members take on distorted characteristics, accentuating their loathing of the victims. In one panel, we see a victim of the mob’s violent aggression, and the older, white woman in the frame looks similar to the woman in Marsh’s image. She greedily, and lustfully, gropes for the man she wants to attack, saying, “KILL HIM!!” In this moment, the woman, and those with her, appear as non-human; they have lost complete control of themselves and who they are. Powell highlights the continuation of racism, oppression, and subjugation when he juxtaposes Barack Obama’s inauguration with images from May 20, 1961.

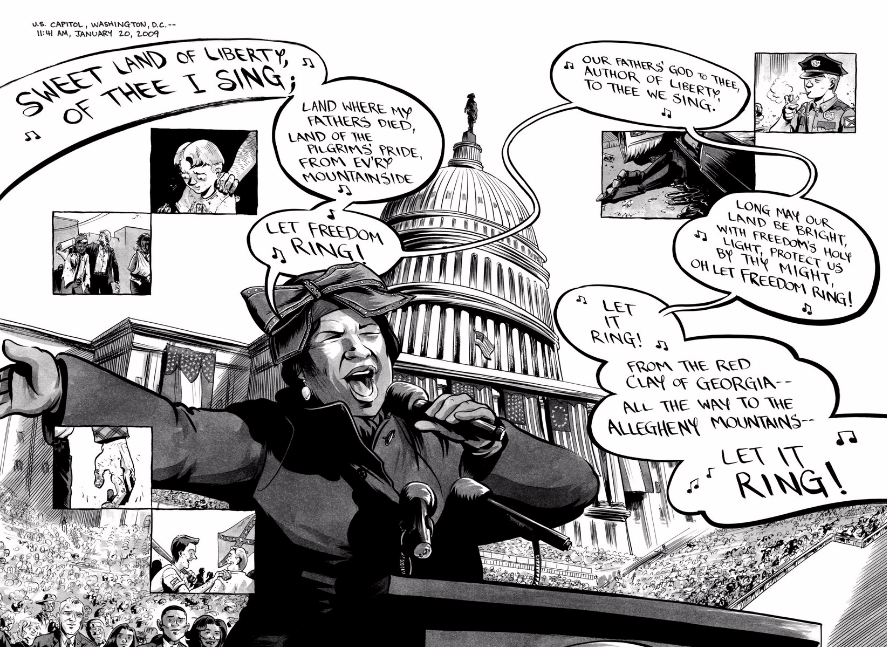

While some of the horde congratulate each other and shake hands, as in the bottom left of the page, we also see the young boy who groped for Zwerg’s eyes at the top left of the page. As with the previous panel, we see his face against a black background; however, here the boy looks down at his bloody hands in disbelief, as if asking himself, “What have I just done?” We know what he has done, and why, and his father’s hand, resting on the boy’s shoulder, lets us know that even if the boy questions his actions, his father will “correct” his thoughts and teach him how to hate soon enough. Below and to the left of the young boy, we see Zwerg and John Lewis together, both bloody, symbolizing unity and equality. All of these images, and more, occur with a double page frame of Aretha Franklin singing “My Country Tis of Thee” at Obama’s 2009 inauguration.

Within these pages, we see the past and the present coming together. Even though March flashes back to the sixties and forward to 2009, I cannot help but look at Powell’s Aretha Franklin in 2009, surrounded by images from May 20, 1961, as a commentary on how far we have come but on how far we still have to go before achieving equality. We see the Confederate Battle Flag, a passive policeman who stood by as the violence erupted, a young boy, a dead woman, and battered victims. As Franklin sings, “Let freedom ring,” she is surrounded by violence and oppression in the adjoining images. Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, the Charleston Nine, and countless others encompass the page with their lingering presence.

By implicating the audience, and delving into the ways that mob violence and racism affect the perpetrator as well as the victim. Marsh, Cadmus, and Powell position the audience in a way that makes them think about their own roles in the continuation of racism and oppression. This is the same technique that authors like Ernest J. Gaines, James Baldwin, Gwendolyn Brooks, William Faulkner, and others deploy, placing the white audience member inside the chaotic absurdity of the situation, turning a mirror back at the viewer to implicate inaction and complacency. In many ways, the overlap of 1961 and 2009 in March confronts the reader head on, asking, “What will you do in the current moment?”

- Marsh was mostly known for his depictions of the urban environment. This is Her First Lynching originally appeared in the September 8, 1934 issue of The New Yorker and later in th January 1935 issue of The Crisis in An Art Commentary on Lynching. Marsh donated the piece to the NAACP, and Walter White called it “the most effective [image of lynching ↩

Good read. I have been studying race in current comics. Marvel has some interesting characters now.