On Freedom and Radicalizing the Black Radical Tradition

Today, Neil Roberts concludes the roundtable on his book Freedom as Marronage. We began with an introduction by Jared Hardesty followed by contributions from James Martel, Annette Joseph-Gabriel, Gregory Childs, and Minkah Makalani. In this final post, Roberts responds to the reviews and offers concluding remarks. Professor Roberts is chair of Religion, associate professor of Africana Studies, and a faculty affiliate in Political Science at Williams College. A high school teacher, debate coach, and NCAA Division 1 soccer player at Brown University prior to graduate school, Dr. Roberts is the recipient of fellowships from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Social Science Research Council, and Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation as well as the President-elect of the Caribbean Philosophical Association. His present writings deal with the intersections of Caribbean, Continental, and North American political theory with respect to theorizing the concepts of freedom and agency. In addition to Freedom as Marronage, Roberts has published in a number of journals, including Caribbean Studies, Perspectives on Politics, and The C.L.R. James Journal and is the editor (with Jane Anna Gordon) of Creolizing Rousseau (Rowman and Littlefield International, 2015) and co-editor of Journeys in Caribbean Thought (Rowman and Littlefield International, 2016). His work A Political Companion to Frederick Douglass (The University Press of Kentucky) is forthcoming and he is currently completing the monograph Dread, Politics, Agency: On Rastafari Political Theology.

Today, Neil Roberts concludes the roundtable on his book Freedom as Marronage. We began with an introduction by Jared Hardesty followed by contributions from James Martel, Annette Joseph-Gabriel, Gregory Childs, and Minkah Makalani. In this final post, Roberts responds to the reviews and offers concluding remarks. Professor Roberts is chair of Religion, associate professor of Africana Studies, and a faculty affiliate in Political Science at Williams College. A high school teacher, debate coach, and NCAA Division 1 soccer player at Brown University prior to graduate school, Dr. Roberts is the recipient of fellowships from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Social Science Research Council, and Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation as well as the President-elect of the Caribbean Philosophical Association. His present writings deal with the intersections of Caribbean, Continental, and North American political theory with respect to theorizing the concepts of freedom and agency. In addition to Freedom as Marronage, Roberts has published in a number of journals, including Caribbean Studies, Perspectives on Politics, and The C.L.R. James Journal and is the editor (with Jane Anna Gordon) of Creolizing Rousseau (Rowman and Littlefield International, 2015) and co-editor of Journeys in Caribbean Thought (Rowman and Littlefield International, 2016). His work A Political Companion to Frederick Douglass (The University Press of Kentucky) is forthcoming and he is currently completing the monograph Dread, Politics, Agency: On Rastafari Political Theology.

On behalf of the AAIHS, thank you all for participating in this exciting roundtable and we hope you all continue the conversation in the days and weeks ahead.

In memory of Cedric Robinson

I was interested in some black history or history of black people where they did something, and they were not being continually the subject of actions and attitudes of other people.

—C.L.R. James (1980)

There is a zone of nonbeing, an extraordinarily sterile and arid region, an incline stripped bare of every essential from which a genuine new departure can emerge.

—Frantz Fanon (1952)

[W]e’ve struggled so long/we’ve cried so long/we’ve sorrowed so long/we’ve moaned so long/we’ve died so long/we must be free, we must be free…But are we really free?

—Angela Davis (2016)

I didn’t plan to be a teacher when I matriculated to Brown University in the mid-1990s. I applied to college aiming to major in chemistry and fulfill my intended scholar-athlete life vocation: to be a professional soccer player. The orbit of footballers I had been surrounded by included Andy Williams, who was dually nearby at the University of Rhode Island and on the Reggae Boyz squad that qualified for the FIFA World Cup for the first time; and Mia Hamm, whose vast talents prior to serving as a US Women’s national team standout, were cultivated in the Washington, DC metropolitan area where I lived after migrating overseas from Kingston, Jamaica with my family.

Everything changed my sophomore year. An injury, a class with an exiled Haitian visiting professor, the refashioning of Brown’s then Afro-American Studies program, the political and social movements locally and internationally. An awakening. Whilst black political thought was not new to me, how to study it and decipher its wondrous contours remained elusive.

No longer.

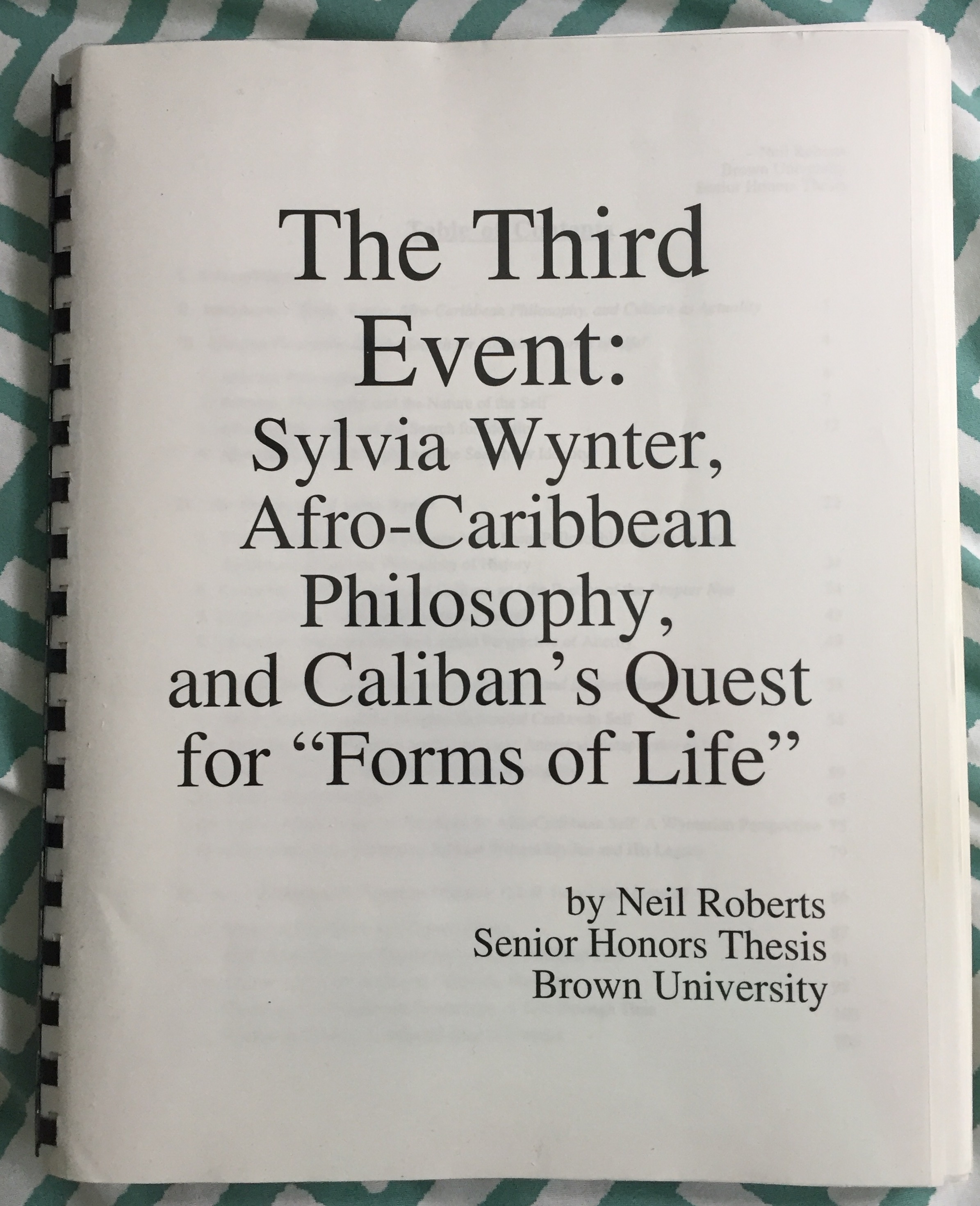

I chose to double-major in Afro-American studies and public policy with specializations in law and the burgeoning area of Africana philosophy. I immersed myself in late night reading groups and attended marches beyond the college gates. A defining moment was when my advisors introduced me to the work of Jamaican novelist, playwright, and critic Sylvia Wynter.1 After nervously writing professor Wynter a letter about my upcoming thesis the summer before senior year, Wynter invited me to discuss in person over a week my interpretation of her scholarship. I framed the final thesis document as an inquiry into Wynter’s “philosophy,” a term she rejected as too provincial. “Thought,” not philosophy, Wynter implored. I explored epistemes, liminality, the origins and development of black studies, claims of the false division between the humanities, social sciences, and physical sciences, ecology, the Human after Man, and the breadth of the twentieth-century Afro-Caribbean radical intellectual and political tradition that Wynter, along with Claudia Jones, C.L.R. James, Amy Ashwood, Marcus Garvey, Jeanne and Paulette Nardal, Suzanne and Aimé Césaire, Wifredo Lam, Frantz Fanon, Walter Rodney, George Lamming, Jamaica Kincaid, Maryse Condé, Peter Tosh, Audre Lorde, Édouard Glissant, Stuart Hall, Gloria Rolando, Carole Boyce Davies, Paget Henry, the New World Group, and Rastafari, among others, helped to forge as they simultaneously imagined what the next century would usher in. This awakening also reminded me of the mentorship and care our elders offer to persons younger than themselves. Guidance, though, shouldn’t be confused with an absence of critical exchange. Wynter never backed down from constructive critique, always with respect.

I graduated from Brown and taught high school for a few years with the lessons of those experiences held close. In the months I wasn’t teaching, I returned to Jamaica to work on policy platforms regarding the death penalty and its discontents in the Caribbean and plans for founding a regional court of justice.

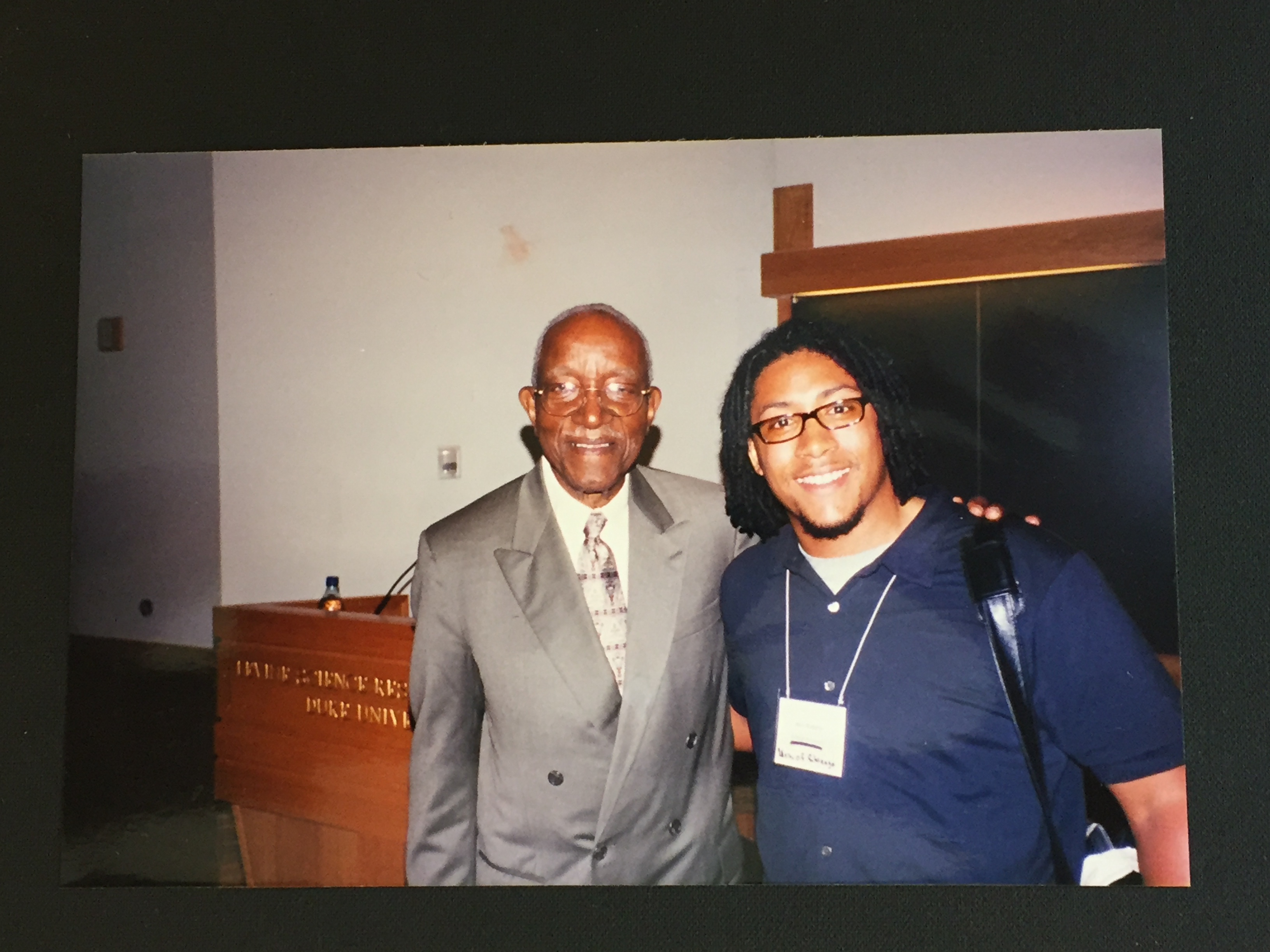

I eventually entered doctoral studies in political theory at the University of Chicago. Political theory, like chemistry, involves dynamism and combinations as well as the decoupling of compounds, real and imagined, to transform the very elements and ideas we hold dear. An unfortunate mythos has been the late modern perpetuation of a dichotomy between “theory” and “history.” Far from incompatible, the two are mutually reinforcing. John Hope Franklin—whom all of us exploring black studies, historicity, slavery, freedom, the history-theory relation, and events where, in James’s words, black people “did something” are forever indebted—demonstrated this. 2

And yet, when reflecting on Franklin’s path-breaking “from slavery to freedom” paradigm, the deft Wynter oeuvre, and the event we now call 9/11, I firmly believed upon entering the professoriate that there was a notable lack in discourses about how we talk about the meaning of freedom, freedom’s connection to slavery, slave agency, and black actors in Africa, Afro-America, the Caribbean, UK, and other regions of the globe that required proper investigation.

How can we develop a conception of freedom that highlights the historical while illuminating the theoretical and generalizable throughout space and time? How are we to reconceptualize freedom to bridge the gulf between its hegemonic articulations in the two main traditions in Western thought—negative freedom (freedom as non-interference and non-domination) and positive freedom (freedom as autonomy, self-mastery, generality, and pluralistic humanism); reject such notions positing freedom in static, immutable terms; indict orders of unfreedom, or existence in what Fanon calls the zone of nonbeing; cut across individual and collective imaginings of the free life; and present the possibility for the realization of revolution?

I dug deeper into processes of creolization and the architecture of the black radical tradition, a tradition transnational in scope, as commentators including Angela Davis, June Jordan, Cedric Robinson, and Achille Mbembe note, and one with profound insights into the imagination and experiences within the realm of the interstitial. 3

The radicalization of the black radical tradition underscores how the lives and lessons of the enslaved, the damnés, are central bulwarks between past and future for revolutionary change and cultivating freedom. Acts of marronage (flight) in their different forms, fugitivity, and interrogation into the liminal and transitional spaces of slave escape between poles of political imagination exemplify this. Freedom is not from–to but rather as.

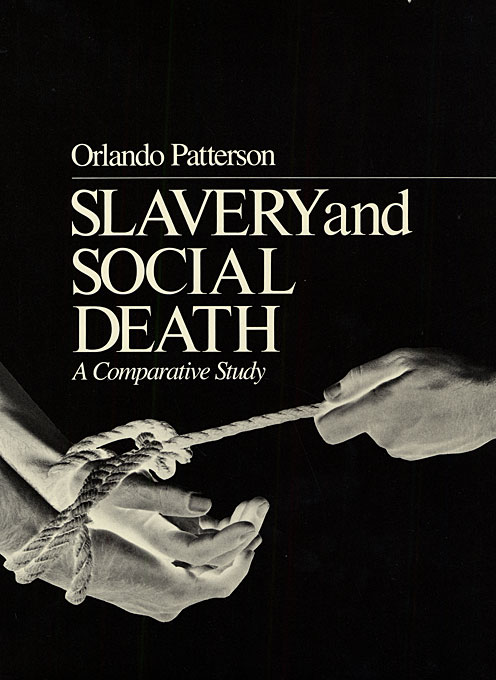

Humans are born enslaved. Humans also have, in spite of this, an intrinsic capacity for agency. Contrary to Orlando Patterson’s celebrated theory of slavery as social death and the deployment of its misguided conception of slaves as living zombies construed as being devoid of the inherent ability for decision-making and action, a view ironically embraced by both camps in the rhetorically rich yet ultimately circular contemporary debate between Afro-pessimists and Afro-optimists, marronage philosophy frames the enslaved as liminal agents and integral catalysts for an order’s naming, constitutionalism, restructuring of civil and political society, and imagined blueprint of freedom (vèvè architectonics). 4 We observe this in antiquity, with the Common Era’s advent, in the period of transatlantic racial slavery, and today, as the movements pertaining to human trafficking, forced sexual work, sweatshop political economy, Occupy Wall Street, prison abolitionism, #RhodesMustFall, and #BlackLivesMatter attest. It shall be so too in the future.

Regarding the aforementioned debate, Afro-pessimists, on the one hand, with their constricted interpretations of Fanon, contend black life is inextricably imbued with social death and a morose daily existence Claudia Rankine refers to as a condition of constant mourning. 5

Regarding the aforementioned debate, Afro-pessimists, on the one hand, with their constricted interpretations of Fanon, contend black life is inextricably imbued with social death and a morose daily existence Claudia Rankine refers to as a condition of constant mourning. 5

Black life appears hopeless and suffuse with nihilism. Afro-optimists, on the other hand, see fugitive hope in the unseen despite what they take, following Patterson, to be the slave’s existence as socially dead—powerless, dishonored, natally alienated—and in spite of the stolen lives of black subjects in modernity. 6 What Afro-optimists propose the unfree do besides taking refuge to overcome their precarious existential condition and transform their stolen lives remains unclear.

However, if we abandon the rigid Manichaean language of pessimism/optimism and reject the mistaken conflation of the idea of social death with Fanon’s radical notion of the zone of nonbeing, wherein existence within its hellishness surprisingly creates the conditions for a salient, genuine upheaval—whether through alterations in an individual’s life or a collective’s mass revolution—, then we enter from modernity’s underside a decolonial framework for describing resistance and the art of becoming free. This allows us as well to clarify the distinct terms “liberation,” “emancipation,” “independence,” and “freedom” that routinely are treated as synonyms. Studies of civil wars, the “black freedom movement,” South Africa after apartheid, and revolutions, for example, reveal the limits of collapsing these terms together when seeking to explain a plane of activities.

It is our struggles, our assertions, our actions to exit the zone of nonbeing at micro- and macro-levels where freedom materializes. Freedom is perpetual and unfinished. Freedom is grounded in acts of flight informed by our experiences and valences of the psychological, physical, social-structural, cognitive, and metaphysical. Freedom encompasses moments that are episodic, durable, and overlapping. Freedom is a state of being, not a place. Freedom as Marronage (henceforth FM) defends these maxims.

FM stretches and challenges conventional understandings of marronage bound to models of history, space, and territory that in my estimation bracket realization of the entirely of the social and political imagination maroons augur. Radicalizing the black radical tradition and our freedom lexicon demands nothing less. This may be exciting to some and problematic to others. Fervent dialogue is thus productive and welcome.

Venues usually publish a single review of a book and not an assemblage of commentary in addition to an author’s reply, let alone text discussion over a week’s time. It is for this reason and more I wish to express profound gratitude to AAIHS, an important organization whose essays on black thought are the first many of read on a daily basis. Moreover, AAIHS accomplishes what much of academia is unable to: establishment of a de-hierarchical mode of intellectual inquiry where respect, strength of argumentation, and interactive conversations between authors and readers are paramount. Thank you to the visionary Keisha N. Blain for proposing the roundtable, the organizationally meticulous Jared Hardesty for moderating the week’s event, and the brilliant James Martel, Annette Joseph-Gabriel, Gregory Childs, and Minkah Makalani for probing essays.

Martel sets the tone for the forum through a wonderful distilling of the four types of marronage FM argues simultaneously manifest themselves in the world. The first two forms, petit marronage (individual fugitive acts of truancy) and grand marronage (isolationist, autonomous, territorially bounded communities outside the parameters of a regime of unfreedom) are models of flight archival records and the extant anthropological and historical scholarship on maroon societies take as normatively accepted.

The other two forms of flight, sovereign marronage and sociogenic marronage, are terms I coin to capture models of freedom that address mass revolutionary politics unencumbered by an individual’s wants or collective isolationist desires. Whereas sovereign marronage posits freedom emanating from the authority of a sovereign entity such as a lawgiver-political leader and subsequently trickling down to a mass of people, sociogenic marronage denotes the non-sovereign forging of freedom by the masses from the bottom up.

Martel’s central intervention questions how disentangling sovereign and sociogenic flight is possible. Martel accurately states sovereign marronage “makes the error of contaminating the freedom of marronage itself with the very concept—sovereignty—that has led to conditions of slavery and oppression in the first place.” He points to post-revolutionary Haiti as emblematic, but notes agents resisting unfreedom didn’t simply disappear. He also asks if there are “examples of marronage within marronage,” e.g. sociogenic acts militating against sovereign contamination. To this effect, Martel invokes the murdered body of Michael Brown. Building upon the idea of “jusrisgenerative black social life,” Martel suggests our refusal of the enslaving yearnings of sovereign power and creation an un-policed law of the people maps onto principles of sociogenesis. I wrestled in Part III with demonstrating the current significance of FM. Martel incisively shows us the crucial stakes for Black Lives Matter and freedom.

Joseph-Gabriel orients readers to the Haitian Revolution chapters she contends are the book’s fulcrum. She astutely discerns a specific aspect of my argument: there wasn’t a singular notion of freedom operative during the dual anti-slavery and anti-colonial Haitian Revolution. Joseph-Gabriel rightly emphasizes my tempered reverence for the lawgiver Toussaint L’Ouverture whose cosmopolitan nationalist vision of freedom nevertheless represents the paradigmatic trappings of sovereign marronage. She invokes C.L.R. James’s magisterial The Black Jacobins, a work, much like W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America, whose integration of history and theory, mediated by political economy, reverberates locally and globally. Where the comparison ends is the storyteller’s viewpoint: for James, it’s the lawgiver; for Du Bois, it’s the masses of fugitives and slaves on general strike. Joseph-Gabriel concludes, with compelling prose, “Sovereign marronage is the Haitian Revolution as told by C.L.R. James.” James admits as much in his posthumously published “Lectures on The Black Jacobins.” Additionally, Joseph-Gabriel asks us to consider the ongoing debates on citizenship, sovereignty, and the mid-twentieth century decision of Antillean polities to become French overseas departments. I would only add to these essential points that FM chapter five broaches the topic of departmentalization in its exegesis of the thought of Édouard Glissant and description of creolizing political theory.

Childs’s essay foregrounds concerns for how one elucidates a transhistorical normative theorize of freedom based on cases particular to historical epochs. Childs perceptively addresses the centrality of Frederick Douglass’s concept of “comparative freedom” to my subsequent typology of marronage. Childs questions the dynamism of the sovereign-sociogenic marronage models; utility of petit and grand marronage; and issue of time via the famous Brazilian quilombo, Palmares. We should indeed think of marronage within and between polities (e.g. Saint-Domingue, France) as occurring in Relation. This is why Douglass, Glissant, and Angela Davis are critical to my claims. Second, I’m in full agreement we should continue to study petit and grand marronage because they reflect freedom dreams actors still have. Third, Childs shows how Palmares defies what I call the limiting politics of recognition enshrined in grand marronage communities. However, we shouldn’t forget Brazil, with its long tradition of quilombo formations, was the last polity in the Americas to abolish racial slavery. The legacy of Palmares’s grand tradition of resistance and black memory exits today in quilombismo movements. But we shouldn’t overlook how territorial isolationism allows for wider slave regimes to flourish.

Last but not least, Makalani explores sovereignty (interrogated by Martel), James’s political thought (noted by Joseph-Gabriel), Davis on liberation and struggle, and Douglass on comparative freedom (discussed by Childs). Yet Makalani articulates a unique exegesis of FM that distinguishes itself by not only meditating on vèvè architectonics, but also postulating the extent to which “sociogenic marronage encounters its limit with the nation-state.” He identifies the text’s Fanonian and Arendtian registers, underscoring my decolonial criticism of Arendt’s disavowal of slavery and slave agency and simultaneous embrace of Arendt’s definition of revolution and the emphases of Arendt and Fanon on human activity. Makalani does, however, remain uneasy about my ostensible slippage between analyzing revolutionary Saint-Domingue and post-revolutionary Haiti where the modern Haitian nation-state took hold. He asks if the nation-state interrupts marronage. If anything the nation-state, with its modern and late modern shortcomings, foments flight. Fugitive and long-durée acts of flight challenge state legitimacy. Structures of governance change across time and typologies of marronage exist prior to, during, and after moments of transformation. Whilst marronage philosophy departs from static negative definitions of fugitivity including black radicals framing freedom as mere escape from Western liberty, marronage fosters world-building, Rastafari reasonings, Wynter’s Human, Glissant’s “prophetic vision of the past,” and, as Makalani highlights, Fanon’s call for us to endlessly recreate ourselves.

Let me once again thank AAIHS, the roundtable contributors, and you the reader for participating in this week’s conversation on Freedom as Marronage. Most works, however provocative, could be strengthened with the sands of time. FM is no exception. If you have been moved in some way to rethink previously held beliefs on freedom and the black radical tradition, then the book served it purpose.

- Key works by Sylvia Wynter include “The Ceremony Must Be Found: After Humanism,” boundary 2 12 (3), 1984: 19–70; “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3 (3), 2003: 257–337; The Hills of Hebron (Kingston: Ian Randle, 2010). ↩

- See John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom: A History of American Negroes (New York: Knoft, 1947). On the history-theory interrelationship, consult Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought (New York: Penguin, 1993); Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon, 1995); Nell Painter, Southern History Across the Color Line (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Christopher Cameron, “Five Approaches to Intellectual History,” S-USIH blog, April 6, 2016: http://s-usih.org/2016/04/five-approaches-to-intellectual-history.html ↩

- June Jordan, Civil Wars (Boston: Beacon, 1981); Lewis Gordon, Existentia Africana: Understanding Africana Existential Thought (New York: Routledge, 2000); Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); Robin Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon, 2002); T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Negritude Women (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002); Charles Mills, Radical Theory, Caribbean Reality: Race, Class and Social Domination (Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2010); Angela Davis, The Meaning of Freedom and Other Difficult Dialogues (San Francisco: City Lights, 2012); Ashley Farmer, “Mae Mallory: Forgotten Black Power Intellectual,” AAIHS blog, June 3, 2016: https://www.aaihs.org/mae-mallory-forgotten-black-power-intellectual/; Achille Mbembe, Politique de l’inimitié (Paris: La Découverte, 2016); Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016). ↩

- Freedom as Marronage examines in greater detail Orlando Patterson’s scholarship vis-à-vis my interpretations of slave agency and marronage. ↩

- See also Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2014). On Afro-pessimism, consult the special issue of rhizomes (2016): http://rhizomes.net/issue29/. ↩

- For notable articulations of Afro-optimism, see Fred Moten’s “The Case of Blackness,” Criticism 50 (2), 2008: 177-218; “Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh),” South Atlantic Quarterly 112 (4), 2013: 737-80; and, with Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013). ↩