On Black Girlhood

This piece was originally published on Public Books and is reprinted here with permission.

The bikini-clad teen is thrown to the ground. An officer, his knee in her back, grabs her braids and slams her head into the grass. She cries, “Call my mama.” When other teens, leaving a pool party, rush to her defense, the officer stands and lunges into the crowd, gun in hand. It is June 2015 in McKinney, Texas. Four months later, in Columbia, South Carolina, a teacher requests an officer’s assistance with a disobedient teen girl. The student has refused to leave class and go to the principal’s office, as the teacher demands. The officer grabs the quiet but noncompliant girl by her neck, overturns the chair in which she is seated, throws her on the floor, and handcuffs her. Most of the other students sit, quietly, heads bent down.

The bikini-clad teen is thrown to the ground. An officer, his knee in her back, grabs her braids and slams her head into the grass. She cries, “Call my mama.” When other teens, leaving a pool party, rush to her defense, the officer stands and lunges into the crowd, gun in hand. It is June 2015 in McKinney, Texas. Four months later, in Columbia, South Carolina, a teacher requests an officer’s assistance with a disobedient teen girl. The student has refused to leave class and go to the principal’s office, as the teacher demands. The officer grabs the quiet but noncompliant girl by her neck, overturns the chair in which she is seated, throws her on the floor, and handcuffs her. Most of the other students sit, quietly, heads bent down.

In both of these instances, the teens were black girls, the officers white men. Videos of each went viral and gained exposure in the national media. These were not the spectacular videos showing the brutal murders of black men and boys, videos that have become all too commonplace. But they do bear witness to the ways that black girls, too, are subjected to police brutality.

Depending on their standpoint, viewers saw different things. Some saw grown men assaulting vulnerable girls; others saw officers doing their duty with resistant teens who refused to take orders. The racial overtones were obvious to most; others insisted race had nothing to do with it. Questions arose: Would this have happened had the girl been white? (Probably not.) Would anyone argue that the officer’s action was justified had he been black and the teen white? (Most definitely not.)

In this extraordinary moment in our national conversation about race, it is essential that we give voice to the black girls who, for far too long, have been uniquely denied an individual identity. At its worst, black girls are portrayed in stereotypical ways: big, loud, and tough-talking. In some instances they are portrayed as resilient, strong, and capable. In the midst of this sit real girls with vulnerabilities, dreams, and challenges. Perhaps one reason this violence could so easily be committed against obviously innocent individuals is that such girls have almost never had a true voice in our culture.

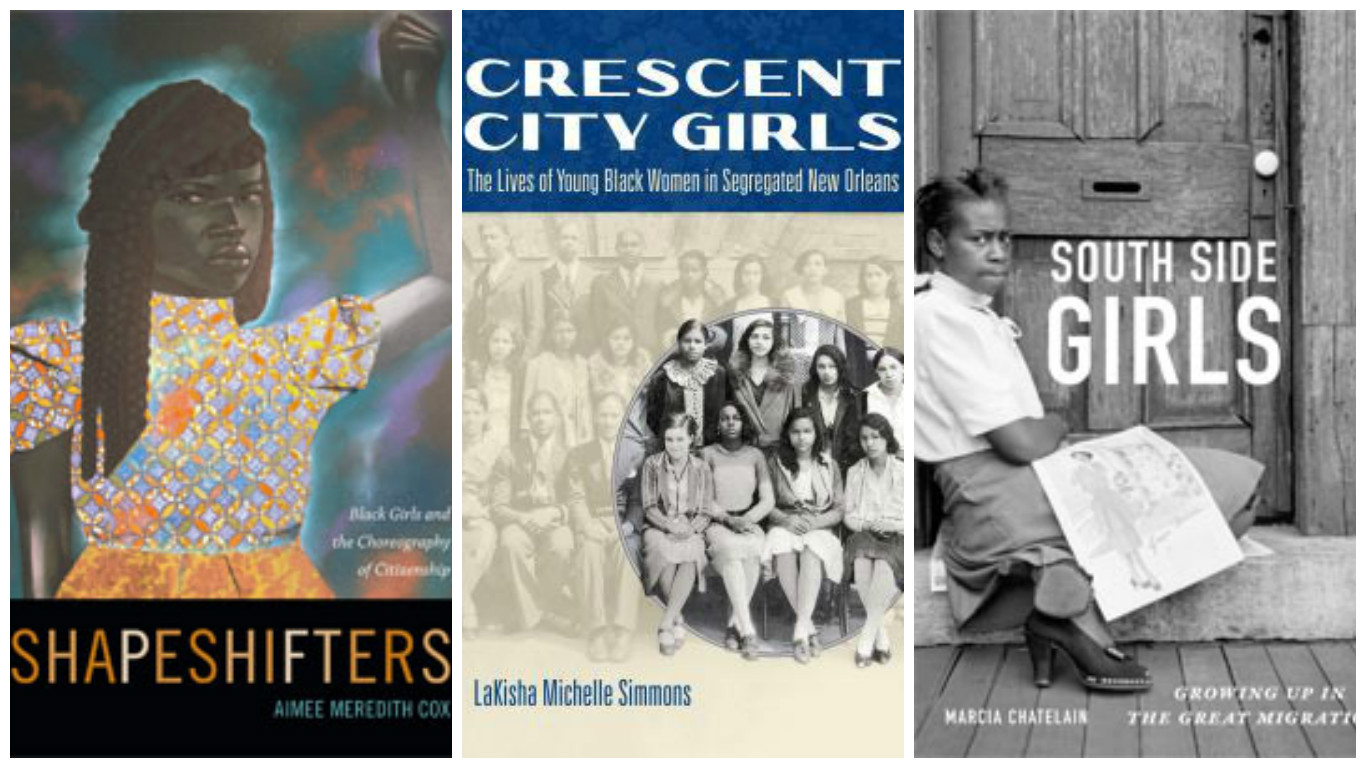

Despite fears of misrepresentation, judgment, or reprisal, black girls have recorded their own impressions, thoughts, opinions, or perspectives; too often, though, our culture has failed to listen to them. Three new books offer up bracingly fresh perspectives on everything from the Great Migration, the Jim Crow era, the Great Recession, and much else from the perspective of black girls. By exposing the hidden trauma of sexual violence in Jim Crow New Orleans, by presenting the fears and aspirations of girls newly arrived in Chicago during the Great Migration, by listening to the individual stories of “at risk” youth in contemporary Detroit, together these three books provide necessary insight into the true lives of black girls. Finally, we can hear the voice of black girls in their own words.

Finding black girls in the archive is challenging. For the most part they have not left dairies, journals, and letters to collections, libraries, or historical societies. Nor have they written published autobiographies. When available, such sources are often those of elite and exceptional black women recollecting their childhoods. When ordinary black girls are located in the archive it is often in writings that record violence against them, list them as chattel, or portray them as one-dimensional stereotypes. In addition, black girls, scholars have shown, have been reluctant to reveal themselves to interviewers and researchers for fear of being misrepresented and misinterpreted.1 In spite of this, perceived absences should not keep us from looking for black girls in the archive.

Historians LaKisha Michelle Simmons and Marcia Chatelain seek new sources and read old ones in new ways. In their hunt for fresh material, the authors mine newspapers, records of black women’s clubs, and the diaries of social workers and students who encountered the girls in community centers and settlement houses. To these they add oral histories, delinquency home records, police reports, and girls’ writings. Even familiar sources are examined here in startling ways. Numerous interviews with teen girls can be found in the famous studies of University of Chicago-trained social scientists such as E. Franklin Frazier, St. Clair Drake, and Horace Cayton. Chatelain reads these sources in ways that refuse earlier stereotyping of young black women. The efforts of Chatelain and Simmons are rewarded with innovative, clearly written narratives that contain the voices of girls shaped by overwhelming historical and social forces. Nonetheless, these girls emerge as historical agents who experience both the pain and joy of being young, female, and black in Jim Crow America.

If the historians are charged with the task of locating black girls in the past, Aimee Meredith Cox builds her own archive by engaging young women in conversation, group dialogue, and interviews that center and value their opinions and analyses.

Focusing on the years 1930–1954, Crescent City Girls opens with the state-sanctioned execution of Willie McGee in Mississippi in 1951. McGee had been accused of raping a white woman, and his is an unfortunately familiar story for anyone acquainted with the history of race and lynching in the United States. But Simmons brings fresh insight to this famed case by examining its coverage in the black press, and in the process reveals crucial new information about black girls in this violent era.

Both LaKisha Michelle Simmons’s Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans and Marcia Chatelain’s South Side Girls: Growing Up in the Great Migration challenge received understandings of the Jim Crow era and the Great Migration. The two, overlapping periods have received a great deal of attention from scholars, but these books decisively incorporate black girls into our portraits of the era. Moreover, they both demonstrate how from the period of enslavement forward, black girls have not benefitted from the assumptions of “childhood’” innocence or the perceived need of protection granted their middle-class white counterparts. (Each recognizes that black girls, especially poor black girls, as young as eight or ten years old, were often employed in domestic service.) In doing so they transform our understanding of the time.

In response to the frenzy to kill McGee for his alleged crime, the Louisiana Weekly ran an editorial that denounced the “dual system of justice” whereby black women and girls “have been raped by white men, [and] seldom is the death penalty exacted.” The editorial then cites the “story of a thirteen-year-old black girl raped by a white truck driver in New Orleans in 1949.” The truck driver was merely found guilty of “carnal knowledge of a minor,” not the much greater crime of rape. History tells us little about the girl. We don’t even know her name. We do know that she was vulnerable to sexual assault by an adult white male, that the law did not recognize her as the victim of rape, and that her story at the time was considered valuable only to the extent to which it illuminated the unfairness of McGee’s case.

Opening Crescent City Girls with McGee’s case is revealing, for it shows how Simmons sets herself the task of looking at “the question of the Jim Crow South anew.” Her attempt to do so is sometimes hampered by the private nature of the violence against black girls: while the lynching of black men was often public spectacle, violence against black women and girls was often hidden in private, domestic spaces. And yet it occurred on a daily basis, paradoxically making the task of isolating and examining such violence all the more difficult.

Though such records are exceedingly rare, Simmons uncovers black women recounting stories of daily sexual harassment by white men. Clarita Reed recalled, “It wasn’t easy. You just got hardened to it. You always expected an insult, regardless.” If black girls were subjected to harassment on the streets of New Orleans, they faced even worse in the places where they worked. The economic reality of many black families sometimes required that girls find employment as domestics in white households. Black families tried to postpone this for as long as possible, for all were aware of the threat of rape. Popular discourse, the media, and even the law eroticized black women and “many white commentators vilified black girlhood by sexualizing young black bodies and by denying black girls childhood innocence.” The prevalence of sexual violence and the insistence on respectability and “niceness” by black families and community leaders only exacerbated the difficulties of black girls’ lives. According to Simmons, black girls in Jim Crow New Orleans found themselves in a “double bind,” which included the segregation and violent white supremacy on the one hand, and middle-class blacks’ expectations of purity and respectability on the other. Respectability required that girls maintain “chastity and honor” in spite of the constant threat of sexual violence by white men.

Simmons’s Crescent City Girls gives its readers the opportunity to explore New Orleans as black girls may have experienced it. New Orleans has Spanish, French, African, Caribbean, and Native American influences; it is also situated in the Deep South. Jim Crow laws imposed binary racial categorizations on these complex formations. They also, as Simmons carefully reconstructs, overlay their racial logics on spatial configurations, prescribing the control of black movement within segregated space. Black girls had to learn how to navigate these spaces in order to protect themselves, while attempting to take advantage of opportunities to be children. They were constantly reminded that they were not wanted and did not belong. Yet this did not deter them from quietly insisting upon their place. This attention to the geography of racially segregated New Orleans is one of the most original aspects of Simmons’s work.

Simmons closes her study with a discussion of “pleasure in black girls’ lives” as it is defined and described by them. She astutely argues that “without making an effort to recover pleasure, black girls’ lives are narrated only by the trauma of Jim Crow. To consider black girls as full human beings, we need to understand their pleasures just as much as their pain.” Sites of “pleasure cultures,” where black girls experienced joy, could be found in schools, churches, and local organizations like the black YWCA. Black girls’ reading and writing culture included poems and narratives, autograph books, and the romance magazine True Confessions, all of which emphasized romance. Thus Jim Crow, although pervasive and destructive, did not fully prevent black girls from expressing and enjoying their humanity.

Marcia Chatelain’s South Side Girls explores the lives and experiences of black girls who joined the Great Migration with their families, in search of greater freedom and opportunity in Chicago. As Simmons does, Chatelain makes creative use of sources as she searches for and finds black girls who have been invisible and unaccounted for in previous histories of the Great Migration.

If history has forgotten black girls in the Great Migration, they were nonetheless of central concern to parents, community leaders, and reformers. Amid the upheavals of migration, black adults “scrutinized black girls’ behavior, evaluated their choices, and assessed their possibilities as part of a larger conversation about what urbanization ultimately meant for black citizens.”

Most studies of the Great Migration turn to the numerous letters written by would-be migrants to the Chicago Defender. This is a mainstay of migration scholarship. Chatelain opens her study with a Defender letter as well, but she cites one written by a 17-year-old girl from Selma, Alabama. The girl identifies the range of domestic and service work she is prepared to do once she arrives in the North. She stresses that she is a student, if only in 8th grade. This suggests her desire to continue her education in the Northern metropolis. The juxtaposition of the need for employment and the desire to attend school tells us a great deal about the condition of black migrant girls: most importantly, that they have the responsibility of adults.

In Chicago, black clubwomen ran institutions like the Amanda Smith Industrial School for Colored Girls and established kindergartens, boardinghouses for single women, and employment agencies. These women considered the protection of black girls as central to notions of black racial uplift. The politics of respectability informed reformers’ and communities’ methods for evaluating and training migrant girls.2 In their arguments for necessary resources for black migrant girls, these clubwomen stressed the girls’ value as future race mothers, women who would serve the project of racial uplift. As Chatelain observes, “this framing of girlhood failed to promote the notion that black girls existed as children.”

Chicago’s religious institutions—both established and those newly formed—competed with popular secular activities for the girls’ time, resources, and energy. In contrast to organized religion, sites of popular culture allowed black girls to “use consumption to don modern identities, rebel against authority, and mediate tensions about their commitment to the secular and the sacred.” This newfound sense of choice was one of the central tensions in black migrant families. Black girls used their earnings to go to roller rinks and the movies. Others took advantage of opportunities for play provided by organizations like the Camp Fire Girls. Interestingly, Chatelain argues that “black leaders and civic organizations used advocacy for black girls’ participation in children’s organizations and made claims about blacks’ fitness for citizenship and social equality.” So even black girls play was politicized.

For those girls who did not participate in these options for organized play, Chicago could be a city of temptation and disappointment. The stresses of urbanization sometimes led to broken families or families that were unable to care for and protect girls. Such girls, Chatelain notes, were often punished for pursuing boyfriends, drinking alcohol, having premarital sex, exposing abuse in their homes, and refusing forced marriage proposals. Nonetheless, like their campfire counterparts, these girls exercised their rights as citizens by using “public schools, Urban League social programs, and health clinics.” As such, “they were also exercising their rights to the city’s institutions.”

Crescent City Girls and South Side Girls transform our understanding of two important eras in American history and demonstrate the ways that consideration of black girls’ experiences provides richer and more nuanced historical narratives. They also provide important context and foundation for the conceptions of black girlhood that we have inherited.

Aimee Meredith Cox’s Shapeshifters: Black Girls and the Choreography of Citizenship focuses on black girls in contemporary Detroit. Cox is an anthropologist who also served as director of the Fresh Start Homeless Shelter (the name was changed in the book to preserve anonymity) and “its transitional living program in Detroit, Michigan, between 2000 and 2008.” The young women of Shapeshifters are the granddaughters of the Great Migration. Their mothers and grandmothers came to Detroit seeking the same kinds of freedom, opportunity, and safety that motivated the women and girls of South Side Girls.

A creative and compelling ethnographic study, Shapeshifters challenges us to revise the ways we think, write, and theorize about young black women, starting with making their voices and self-analyses the subject of the book. Rather than analyzing the girls’ narratives through the lens of academic theories, even those of black feminists, Cox asks that “we open ourselves up to a conversation with them.” Thus she takes seriously the terms the young women use to describe and theorize their own experiences and subjectivities.

For instance, Janice, one of the young women with whom Cox has the most sustained and consistent relationship, uses the term “missing the middle,” which she describes as: “The way we always have to think about how other people see us and compare it to how we see ourselves.” For Janice, “the middle” is “the truth you don’t see” in media, popular culture, and academic representations of black girls. She notes, “There’s a lot in the middle, but who’s trying to hear that.” Janice describes a kind of DuBoisian double consciousness, in which black girls are fully aware of the ways that dominant discourses define them. Girls recognize these as harmful fictions that impact their lives and yet they are self-aware enough to maintain a sense of themselves as separate from those definitions. They recognize the value and worth of the “middle.” Janice asks, “Who’s trying to hear that?” Fortunately, Aimee Cox was, and the book is an invitation for readers to listen as well.

Terms like “in the middle” join Cox’s own critical vocabulary and offer concepts that better approximate the experiences, expressions, and longings of the young women. The title of Cox’s work contains two of the three terms that constitute the most significant interventions and contributions of this study: “shapeshifting” and “choreography.” Of “shapeshifting,” Cox writes: “In the context of a homeless shelter in postindustrial Detroit, shapeshifting most often means shifting the terms through which educational, training, and social service institutions attempt to shape young Black women into manageable and respectable members of society.”

As a former dancer, Cox finds the term “choreography” especially useful for the ways it seeks to order bodies in space, the ways it embodies “meaning making, physical story telling, affective physicality.” The young women of Shapeshifters “stay in their bodies to rewrite the socially constructed meanings shackled to them.”

Throughout her book, Cox mobilizes all of these terms as she shares the ways young women engage biological families and create alternative ones, navigate institutions meant to serve them, and seek to maintain a sense of themselves as fully capable agents in their own lives and communities.

Early in the book, Cox asserts that “Black girls are not the problem. Their lives do not need sanitizing, normalizing, rectifying, or translating so they can be deemed worthy of care and serious consideration.” Because of the way she renders the girls with whom she has worked with such care, because she creates a space for them to speak their truths, her work contributes to our own shapeshifting into beings who are concerned about all girls, just because they deserve our care and consideration.

- In 1989, historian Darlene Clark Hine encouraged scholars to attend to noneconomic reasons black women joined the Great Migration, especially to the pervasive threat of sexual violence by white men. Hine theorized that this motivation was difficult to uncover in the archive because of an overwhelming silence on the part of black women and their communities. She identified a “culture of dissemblance” among black women whereby they shielded their inner lives as a means of self-protection. This culture of dissemblance and secrecy extends to the silences we find in the archive. See Darlene Clark Hine, “Rape and the Inner Lives of Black Women in the Middle West,” Signs, vol. 14, no. 4 (Summer 1989), pp. 912–920. ↩

- In 1993, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham introduced the term “politics of respectability” to the field of African American History. She writes: “The politics of respectability emphasized reform of individual behavior and attitudes both as a goal in itself and as a strategy for reform of the entire structural system of American race relations.” Since Higginbotham’s introduction of the concept, it has become subjected to critique by activists and scholars alike for its limitations and its failures as a political and personal strategy. See Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, “Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church” (Harvard University Press, 1993). ↩