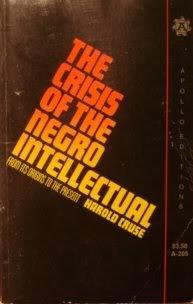

Not a Classic: The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual

*This post is part of the Society for U.S. Intellectual History’s recent roundtable on Harold Cruse’s The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967). Click here to read Robert Greene II’s introduction to the roundtable.

Christopher Lasch praised The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual as a “monument of historical analysis.” He was wrong. Crisis did much to stimulate African American intellectual history and remains a fascinating source for intellectuals historians today. But fifty years later, Harold Cruse’s book holds up poorly as a work of intellectual history.

Cruse’s discussion of “integrationism” is particularly off the mark as intellectual history. In large part, The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual is an attack on the interracial left of the 1930s and 1940s and the interracial civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Cruse declares all the intellectuals associated with these movements to be fundamentally “integrationists,” devoted to assimilating African Americans into American society on the basis of liberal individualism. To Cruse, integrationism forms a coherent if flawed ideology, one that fails to recognize the basic pluralist nature of American political and cultural life.

He sees integration as an illusory goal because white America itself is not homogenous. African Americans should rather seek to preserve their “group integrity” and thereby achieve political and cultural power together, just as earlier white immigrant groups had done. To Cruse, integrationism at best serves only the interests of the African American middle class.

Cruse’s “integrationism” is the flimsiest of straw men. He criticizes those who “see integration as solving everything” (12) describing “a legion of zealots for whom integration has been hypostatized into a religion” (13). One wonders who on Earth Cruse is talking about. Very few African Americans spoke about “integration” as a goal in and of itself (rather than as a tactic to achieve freedom and equality). I am not aware of anybody who self-identified as an “integrationist” at the time Cruse was writing. While Cruise does offer specific and at times penetrating critiques of particular “integrationists” such as Lorraine Hansberry and Paul Robeson, his crucial definition of the category of “integrationism” occurs without reference to specific individuals.

To be sure, the concept of “integration” was a central one to civil rights discourse. But it could mean very different things. Cruse reduces “integrationism” to its mildest form of color-blind individualism. But the interracial socialism of an A. Philip Randolph and the “beloved community” of Martin Luther King Jr. and SNCC hardly fit this model. Cruse thought “one of the great traps of racial integrationism [was that] one must accept all the values (positive or negative) of the dominant society into which one struggles to integrate.” But this is total nonsense. Civil rights leaders and intellectuals wanted to change American society in fundamental ways. As James Baldwin famously asked, “Do I want to be integrated into a burning house?” Much of what gave Cruse’s text force as a fresh and radical text came from his attack on integrationism. But one wonders just how radical Cruse’s stance actually was. I find it very odd that Cruse was able to pass off his pluralism, literally ripped from liberal-cum-neoconservative sociologist Nathan Glazer, as somehow more radical than the visions of James Baldwin and King.

To be sure, the concept of “integration” was a central one to civil rights discourse. But it could mean very different things. Cruse reduces “integrationism” to its mildest form of color-blind individualism. But the interracial socialism of an A. Philip Randolph and the “beloved community” of Martin Luther King Jr. and SNCC hardly fit this model. Cruse thought “one of the great traps of racial integrationism [was that] one must accept all the values (positive or negative) of the dominant society into which one struggles to integrate.” But this is total nonsense. Civil rights leaders and intellectuals wanted to change American society in fundamental ways. As James Baldwin famously asked, “Do I want to be integrated into a burning house?” Much of what gave Cruse’s text force as a fresh and radical text came from his attack on integrationism. But one wonders just how radical Cruse’s stance actually was. I find it very odd that Cruse was able to pass off his pluralism, literally ripped from liberal-cum-neoconservative sociologist Nathan Glazer, as somehow more radical than the visions of James Baldwin and King.

Cruse’s key historical claim is that “American Negro history is basically a history of the conflict between integrationist and nationalist forces in politics, economics, and culture, no matter what leaders are involved and what slogans are used” (564). Reading this today reminds me of weak undergraduate essays that place undue weight on the “integrationist versus nationalist” framework. I recall essays by C students who, when asked to analyze texts from the Capper and Hollinger reader, chose King and Malcolm X because they felt they understand the differences between them based on what they learned in high school. Today’s historiography has proceeded well beyond the time-worn “integrationist” versus “nationalist” theme.

Crisis is not an intellectual history. It’s a polemic. Cruse is often incisive in his critiques of both “integrationism” and “nationalism.” But he writes as if there is some easy solution out there to the dilemmas faced by African American intellectuals. Despite his materialist analysis of how white philanthropists distort African American culture, Cruse’s narrative is essentially one of the “treason of the intellectuals,” as if only more intelligence or courage from individuals were required. As is typical of this genre of polemic, he vastly overstates the importance of intellectuals, absurdly proclaiming that

With a few perceptive and original thinkers, the Negro movement could long ago have aided in reversing the backsliding of the United States toward the moral negation of its great promise as a new nation among nations.”

In short, Crisis does not deserve the status as a classic text of African American intellectual history. However, it nevertheless remains valuable text for intellectual historians. Regardless of its merits, the concept of “integrationism” was a significant one for the Black Power era and Crisis was one of two key book that introduced it (the other was, Stokley Carmichael and Charles Hamilton‘s Black Power, published the same year). For intellectual historians, Crisis is a poor guide but a key signpost.

*Click here to read Cedric Johnson’s response to this review on the U.S. Intellectual History blog.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Harold Cruse never did, as far as I know (and I knew him) present his 1967 book as a work of historical scholarship, or see himself as an historian. The book polemical, focused on the failures of radical movements and Black intellectuals; it drew on Harold’s deep knowledge of the past and was shaped by Harold’s roots in the Old Left and by his break with the CPUSA and its position on Black America. What made the Crisis of the Negro Intellectual was its impact upon publication, with its searing argument that Blacks in America faced a situation far more dire that what the Civil Rights movement recognized in 1967. On this pessimistic assessment, I think Cruse has largely been vindicated by the subsequent half century. He rejected civil rights triumphalism before it was widely practiced.

Still, the book has many limitations, as noted here by others. Harold Cruse never earned any college degree; he was a true organic intellectual, born in Virginia and raised in Harlem, inspired as a youth by the Theater. Late in life, he was appointed to (what I believe was his first academic job) to be the founding director of the U. of Michigan’s Black Studies program. He was always an outsider to academia even as he stayed at Michigan.