NMAAHC and the Internationalism of African American History

This Saturday, on September 24, 2016, the National Mall will be filled with black church groups and middle school class trips for the inauguration of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). While recent media profiles of the institution frequently denote the museum’s historical significance (and rightly so), they also capture NMAAHC’s desire to emphasize—at least rhetorically—the distinctly American character of African American life.

“African American history is American history” has become a common theme touted by the museum and its founding director, Dr. Lonnie Bunch, III. The museum has also historicized its genesis as a 100-year-long campaign to force America to recognize the contributions of its black citizens. In doing so, NMAAHC has fashioned itself as not merely a black museum, but an institution that offers all Americans the opportunity to understand American history through an African American lens.

Although African American identity cannot be fully understood without highlighting its connection to the United States, NMAAHC’s desire to tell a quintessentially American story obscures the many ways in which African Americans have radically defined and redefined themselves beyond the American nation. Black nationalists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, for instance, were convinced that true freedom and self-determination for black people were unachievable within the confines of America. They therefore imagined new possibilities for racial unity and national identity that transcended U.S. borders. Likewise, Ethiopianists and Pan-Africanists tapped into a transnational Afro-diasporic community that had the potential to liberate black people on every continent from global white supremacy. Within NMAAHC’s collection are issues of The Crisis, the brainchild of Pan-Africanist scholar W.E.B. Du Bois who often used the NAACP’s official magazine to connect the experiences of black Americans to Afro-descended peoples across the globe.

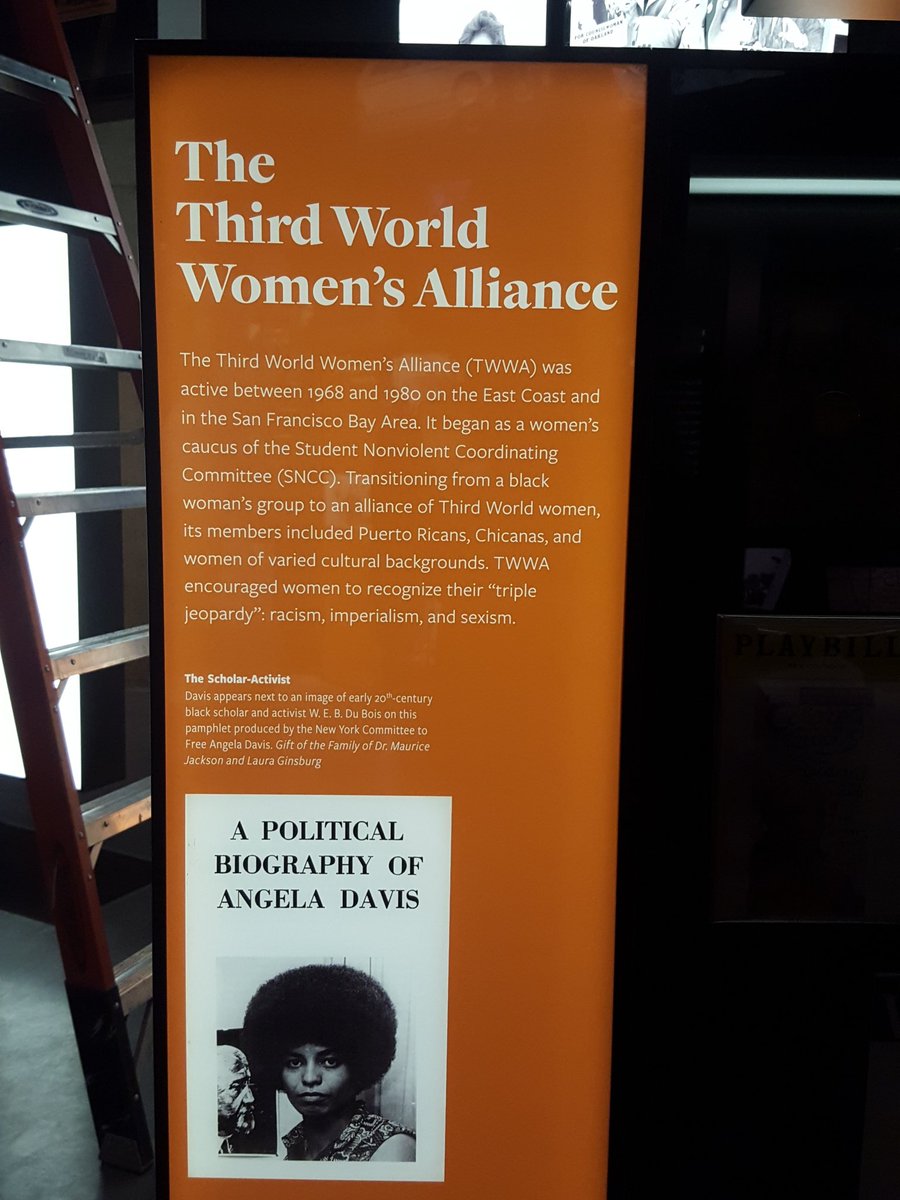

Other black Americans identified racism as a global phenomenon and counted themselves among the “darker races” of the world at the turn of the twentieth century and the “Third World” a few decades later. Recognized in the museum’s collection for her revolutionary hair care empire and civil rights activism, Madam C.J. Walker also co-founded the International League of Darker Peoples in 1919 alongside the architect of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Marcus Garvey, and labor rights activist A. Philip Randolph. As “darker peoples,” Walker and the organization built Afro-Asian solidarity networks in order to combat white supremacy and global imperialism. In its history exhibition, NMAAHC features the Third World Women’s Alliance, a revolutionary coalition of African American, Chicana, Native American, and other women of color whose distinction as “third world sisters” linked them to non-aligned revolutionaries in their collective struggle against racism, imperialism, and sexism.1

For the followers of Elijah Muhammad and African American members of other Islamic sects, their faith linked them to an international Muslim community. As a member of the Nation of Islam, Muhammad Ali—whose headgear and boxing robe will be on display in the museum’s Sports Gallery—defined himself as an “Asiatic Black Man” with ancestral and spiritual ties to continental Asians and Africans. NMAAHC also houses a tape recorder used by Malcolm X during his tenure at Muhammad Mosque No. 7 of the Nation of Islam where he identified as Black Asiatic as well. Even after Malcolm X left the Nation, his conversion to Sunni Islam kept him connected to an international network of worshipers throughout the world.2

Not only did black Americans reimagine themselves globally along racial, ancestral and religious lines, but also in terms of international politics. Black radicals of the early twentieth century including Paul Robeson, Audley Moore, and Claudia Jones turned to Communism as a political identity that allowed them to combat racism, imperialism, sexism, and capitalism simultaneously within and outside U.S. borders. By the 1960s and 70s, Marxism-Leninism, Maoism, and the political philosophies of African, Caribbean, and Latin American revolutionaries had developed into a transnational language. Through this shared vernacular, black activist organizations like the Black Panther Party—a group featured in NMAAHC’s inaugural exhibit—communicated with other oppressed peoples all over the world.

African American identity cannot be bound by U.S. borders, and NMAAHC’s collection is evidence of this fact. Yet, NMAAHC’s domestication of African Americans not only distorts African American history, but also sanitizes African American politics of its emphasis on revolutionary self-definition. As an African American museum, NMAAHC must not forget the radical roots of “African American” and “Afro-American”—nomenclature created and appropriated by Afro-descendants within the U.S. that laid claim to an Afro-diasporic past and present when neither “American” nor “Negro” could suffice. Constantly questioned about her Americanness when studying abroad in Europe, Mary Church Terrell—who NMAAHC will undoubtedly recognize for her early contributions to creating a national memorial celebrating African American achievements in 1929—proudly identified herself as African-American:

I am not ashamed of my African descent…If our group must have a special name setting it apart, the sensible way to settle it would be to refer to our ancestors, the Africans, from whom our swarthy complexion comes.3

As the first national museum dedicated to African American life, NMAAHC has the opportunity to challenge conventional boundaries of what constitutes African Americanness, and in turn, what constitutes Americanness. On many fronts, NMAAHC has already begun doing so. The museum intends to exhibit the breadth of African American history which includes slavery, segregation, lynchings, police brutality, and other forms of legal and extralegal violence. They are also advancing initiatives to facilitate conversations about race and racism in America and are expanding the museum’s collection to reflect the gender and sexual diversity integral to understanding African American life. However, NMAAHC should remain cautious of circumscribing African American history within the well-defined boundaries of the United States or risk dislocating African American history from its profound connection to the world.

- See Stephen Ward, “Third World Women’s Alliance: Black Feminist Radicalism and Black Power Politics,” in The Black Power Movement: Rethinking the Civil Rights-Black Power Era ed. by Peniel Joseph (New York: Routledge, 2006), 119-144. ↩

- See Sohail Daulatzai, Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Freedom Beyond America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012). ↩

- Mary Church Terrell to Editor of the Washington Post, 14 May 1949, in Letters of the Century: America 1900-1999, ed. by Lisa Grunwald and Stephen J. Adler (New York: The Dial Press, 1999), 355. ↩

Awesome article! History is an eye opener! Can’t wait to visit the NMAAHC

Excellent article! First of all, I am absolutely ecstatic that finally we will have a museum on the National Mall that speaks to the African American experience in this country. I can remember as a young girl being taken to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and while enjoying what I saw, I can remember thinking that I saw nothing that looked like me, an African American girl growing up in the United States. So, even though this is a belated recognition of all that my people have contributed to this country, I am excited about the museum’s presence in our Nation’s Capital. Secondly, I understand what the author is conveying in his essay. We should take a look outside of America’s borders to also capture the struggle for freedom and self-determination by people of color. In time my friend, in time.

Yes, but.. Is it not good to acclaim this august footprint, an institution of recognition, acknowledgement and welcome? It offers a central place to rest, reflect and rejoice, as well as one springboard for future endeavors.

On this basis, many, no, countless, heartfelt Congratulations!!! are very thankfully offered.

Awesome article that encapsulates my glad, yet slightly mixed feelings about the museum. However, as a museum it is by nature an adaptable, community-focused entity, so I look forward to the future, where curators, historians, and the like will fill in the narrative gaps.

This article is outstanding and informative, It definitely is an open invitation to go see.

Good work family. Hope to visit one day.