New Directions in Black Women’s History

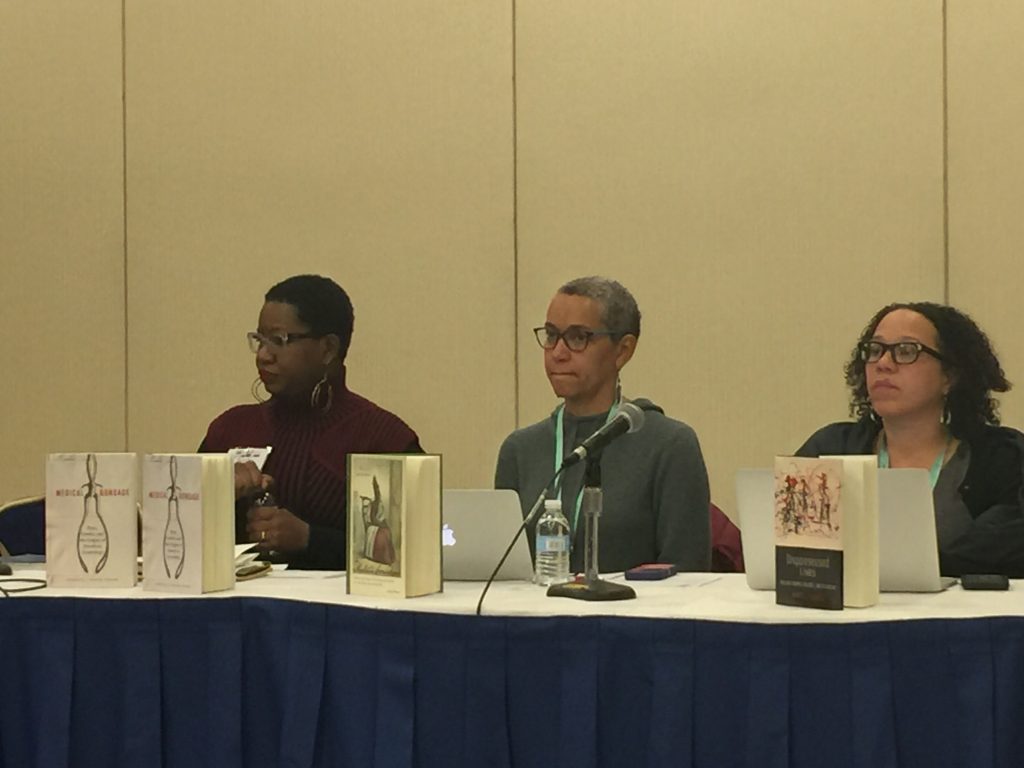

The New Directions in Female Bondage roundtable at this year’s Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association (AHA), featured the recent monographs of Lisa Ze Winters, Marisa J. Fuentes, Sasha Turner, and Deirdre Cooper Owens. It produced generative discussions around slavery, violence, intimacy, pleasure, reproduction, archival disappearance, and historical methods. The idea for the roundtable was Jennifer Morgan’s, who, as an AHA Program Committee Member invited me to put together a panel of scholars whose work engaged this year’s conference theme, “Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism in Global Perspective.” While the roundtable participants simply came down to a question of available scholars (Katherine Paugh and Sarah Franklin, for example, had to cancel their participation), the discussion reflected the possibilities opened up by decades of scholarship on Black women’s history and Black feminist thought.

Just as the panel represented only a subsection of scholars interested in questions of race, gender, and slavery, what I will share here is not an exhaustive overview of the roundtable. My reflection also expands some of the discussion points beyond participants’ comments and includes examples from the individual books.

Archival limitation was a foremost concern for roundtable participants. Antebellum medical records, Cooper Owens explained, not only detailed the “brutal and inhumane” medical treatment enslaved women were forced to undergo. These records were “based on incorrect biological knowledge about black women’s bodies and what they could endure physically.” The transference of violence experienced in the flesh to archival documents that enumerated the enslaved as property, objects to be counted, and bodies to be punished, Fuentes added, it “made the lives of the enslaved disappear.” What remained in the archives were not whole subjects, but rather “fragments” that reflect slaveholders’ claims on the enslaved. How then can we rely on the authority of the archive to reveal the life of enslaved subjects, when the very act of archival production “mutilated” the women we seek to historicize? Fuentes asked.

The fragments produced by the archives require historians of enslaved subjects to (re)invent their methodologies. For Cooper Owens, such unorthodox approaches involved her reading the archive “with the set of experiences that Black women have,” and through the “cultural knowledge” that Black women possess. For example, in her epilogue Cooper Owens shared how the Black community’s experiential knowingness that elite white men maintained sexual relationships with Black women shaped her own study of a revered white elite man. Her “cultural socialization as an African American woman influenced [her] to read the sources differently” than those who previously wrote “about the birth of American gynecology.”

(Re)engaging archival fragments through such personalizing acts as naming, and in Fuentes’s book, using the names of individual women to title her chapters, allows us to defy the logic of the archives constituted from the perspective of slave masters. “By changing the perspective of a document’s author to that of an enslaved subject,” Fuentes reimagined the experiences of such enslaved women as Jane who fled captivity. We know of Jane through her runaway advertisement. But the ad only reveals the “discourses and desires of a man that claimed to own her.” It tells us little to nothing about who Jane was and what it meant to be a fugitive woman in eighteenth century Bridgetown, Barbados.

Culling together a variety of historical documents–traveler’s accounts, maps, surveys, and records of punishment–about Bridgetown at the time of Jane’s flight, Fuentes illustrated what she means by reading the archives expansively by reconstructing what Jane may have seen, sensed, and felt. In her book, Fuentes wrote, “Walking along the careenage, Jane would smell the seawater, mixed with sour and dank smells of too many people in too small an area, and if she passed the Cage, which held captured runaways, she would have seen the sweat and sensed the fear of the occupants inside.”

Ze Winters similarly challenged archival limitations by elaborating what we might call a methodology of care. Ze Winters asked, “what does it mean to be careful about something one imagines might be or could be there but might be something that should not be told or perhaps not even be there?” In responding to her own question, Ze Winters put forth the concept of “sacred archives,” as a way of “centering Black diasporic imaginations…against white colonial ones.” In her book, Ze Winters analyzed the ways free(d) women of color adorned their bodies through the lens of sacred diasporic traditions, such as Haitian Ezili, thereby destabilizing easy assumptions that free(d) women of color attended to their physical appearance to entice the white, male gaze. Analyzing the sartorial practices of free(d) women of color through such religious practices as Ezili reorients readers to think about how these women “function[ed] as social beings” rather than fixate on European conveyance of their beauty and ornamentation to titillate the senses.

Ze Winters invoked the work of the late Stephanie M. H. Camp, who wrote,

As much as [enslaved] women’s bodies were sources of suffering and sites of planter domination, women also worked hard to make their bodies spaces of personal expression, pleasure, and resistance…. When they adorned their bodies in fancy dress, rather than degrading rough and plain clothing, rags, or livery that slaveholders dressed them in, they challenged the axiomatic (doxic) quality of their enslaved status.”

Ze Winters invited us to consider “what dress might reveal about the relationship between enslaved and free(d) women of color as they shared and reproduced a repertoire and rituals of adornment and toilette that marked their status and belonging within diasporic communities.” To imagine the skill and time invested in such grooming practices is to imagine the intimate lives of the enslaved beyond white surveillance and beyond colonial and archival investment in the sexual relations of women of color.

Over the course of the roundtable discussion, I offered examples of rituals and customs enslaved women created in response to the needs and challenges of childbirth to illustrate non-sexual intimacies among enslaved women. Through such practices as mothers nursing each other’s children, developed in part because Black women suffered from difficulty breastfeeding, enslaved women created a variety of healing and cultural practices to attend the needs of laboring women and their infants. The networks of friendship, support, and intimate bonds enslaved women cultivated around childbearing is also an example of the possibility of (re)reading the archive from the perspectives of the enslaved.

My remarks suggested that such perspectives could be erased when such theoretical concepts as “flesh” and “social death” are taken to represent the lived reality of enslavement. The concept of flesh, developed by Hortense Spillers, brilliantly captures how slavery stripped enslaved people of personhood, kinship, gender identity, and “every feature of social and human differentiation” by defining them as inheritable property and marketable commodity. Flesh offers poignant language to capture the violent erasures of slavery, but it can mute the possibility of the enslaved creating alternate, hidden realities in spaces beyond the grasp and imagination (however temporary) of slaveholders. The dynamic nature of slavery requires multiple analytical tools that capture both the conceptual logic of slavery and the daily struggles between enslaver and enslaved. My work uses a body-centered analysis, which implies inherent tensions between external claims imposed on the body and the disruption of such claims, offers an additional framework of contending with the dissonance between the racial logic of slavery and the quotidian. When enslaved women nursed each other’s children, for example, they also disrupted racialized ideas about the superhuman ability of the Black body to perform reproductive labor without difficulty.

Audience commentary invited deeper explorations into ongoing debates about the private/public binary. While some scholars rightly insist that there has never been a true separation between the public and the private, such claims can easily elide how racialized slavery implicated gender relations. One discussant highlighted the importance of exploring how slavery produced privacy for white people, and how the exposure of Black women’s reproductive lives to the market foreclosed private life as an option for the enslaved. How does thinking through privacy as a conceptual issue, rather than an experiential reality, yield a richer analysis of how historical subjects constructed and navigated gendered racial hierarchies? Public/private debates generated thoughtful discussions about intimacy, pleasure, intimate violence, and how we uncover (and the ethics of uncovering) the private life of the enslaved.

The subject of pleasure and intimacy provoked lively debates as discussants grappled with what pleasure meant for the enslaved and the (im)possibility of pleasurable touch when slavery depended on violating the enslaved through touch. The question of how to dislodge pleasure from sexual relations pressed us to think carefully about centering sexual interactions as primary sites of pleasure in a world where oppressive power relied on sexual violations.

Memory and word limit won’t allow me to capture all the salient points raised. But I think it fitting to nod to the roundtable’s significance beyond strict state of the field conversations. While some details of the discussion escape me, the feeling of optimism and new possibilities for the future of Black women’s history lingers.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.