New Challenges, New Ideas, and Black Reformers of Pittsburgh

This post is part of our online roundtable on Adam Lee Cilli’s Canaan, Dim and Far.

In a recent Twitter post, author and professor Randal Maurice Jelks posed an interesting question: why do Black scholars embrace W.E.B. Du Bois but dismiss Booker T. Washington? Jelks’s question points to a larger debate within Black intellectual history and collective memory. An ideological conflict between the two men developed in the late-nineteenth century and carried over into contemporary historiographical debates. Du Bois’s scholarly ambitions have shaped the field over the past century, yet Washington’s accommodationist approach – exemplified in his 1895 Atlanta Compromise Speech – did not attempt to challenge white supremacy. According to Jelks’s tweet, though, these conflicting viewpoints are not that simple. While Du Bois formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People alongside white activists, Washington developed the Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black college in Alabama. This debate presents Du Bois and Washington’s ideas at opposite ends of the spectrum, but it fails to account for the broader ideologies that impact ordinary Black Americans prior to the Second World War or to accurately depict how we remember activism before the civil rights movement.

Adam Lee Cilli’s Canaan, Dim and Far confronts this scholarly debate while also illuminating the ideological scale and scope of early-twentieth-century Black reform work in Pittsburgh. Cilli argues that racial hostility as well as the changing social and political landscape in the Steel City required flexibility among middle-class activists. The author asserts that Pittsburgh, as a center of industry and labor activism that hosted a large migrant population and robust racial advancement institutions, offers a critical window for examining the “dynamic relationships that reformers developed with migrants, steel executives, labor leaders, communists, progressives, and politicians in order to advance their goals.” These goals were wide-ranging and connected to multiple issues. Indeed, this study illustrates how various groups formed political alliances and shaped ideas of racial equality to meet the evolving challenges confronting early civil rights activists. Although Cilli references Du Bois and Washington, the author goes beyond this example of ideological differences to examine the pragmatism of Black reformers alongside notions of racial uplift, migration, education, labor, and criminal justice in Pittsburgh.

The primary strength of Cilli’s Canaan, Dim and Far is the author’s ability to balance multiple themes throughout the book. Each chapter is devoted to a single element of Black reform efforts, yet Cilli’s thoughtful connections present these initiatives as a movement and related set of goals to promote racial equality in the years preceding the heroic civil rights era.

Taking a chronological approach, the book begins with early migrants in the 1910s and their encounters with reformers working in Pittsburgh. According to Cilli, “racial, regional, and class identities shaped their experiences,” referring to southerners just arriving in the city and reformers that greeted migrants with housing, employment, and education assistance as well stereotypes and judgment. Notions of racial uplift frame Cilli’s description of the Urban League of Pittsburgh (ULP), as the organization helped migrants that struggled with new forms of discrimination in the North. Cilli, however, begins to transition away from uplift ideology to early civil rights organizing as Pittsburghers confronted Jim Crow segregation and incarceration. Through the efforts of the Pittsburgh National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (PNAACP), reformers issued legal challenges to segregation and discrimination in the city, opening educational and employment opportunities for Black residents.

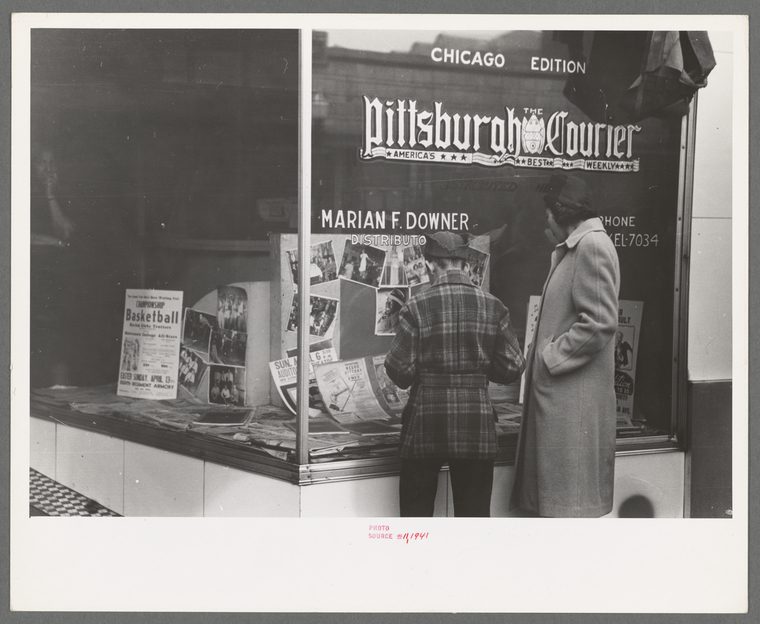

In the second half of the book, Cilli builds on Black reformers’ civil rights focus in electoral politics, education, and employment. As Robert L. Vann, publisher and editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, became a larger political figure, he could swing the Black voting bloc in Pittsburgh in multiple directions in local, state, and even federal elections. In fact, Cilli explains that reformers’ ideological flexibility allowed them to support “laissez-faire capitalists and committed socialists.” Cilli then re-visits the ULP’s efforts to open access to education for Black students. In this section of the book, though, Cilli explicitly argues that the ULP shed its racial uplift framework and embraced a more inclusive, justice-oriented approach to civil rights. Finally, the book concludes with Black Pittsburghers’ involvement with the Double V campaign, connecting the interests of middle-class and working-class residents to engage in civil rights organizing. Although the study takes place in one city, Black reformers’ organizing efforts connected various political figures, groups, and ideas to achieve their goals – an opportunity for Cilli to incorporate multiple themes throughout this study.

According to Cilli, Black reformers prior to the civil rights movement are understudied, but also misrepresented through ahistorical, class-conscious arguments. He also argues that scholars might underestimate the difficulties faced by early-twentieth-century activists, which required various ideological shifts and revolving political alliances to achieve certain goals. This is central to the book’s argument, but again points to the larger debate occurring within the field of Black intellectual history. It is clear throughout the book that Cilli is less interested in easily categorizing Black reformers and emphasizes that the path to racial justice moves through multiple ideologies and practices. Perhaps Cilli’s contribution to recent scholarship is best summarized in his investigation of the “range of perspectives and ideologies… between ‘freedom can wait’ and ‘freedom now.’”

While the Du Bois-Washington binary often frames scholarly and popular interpretations of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, Cilli’s Canaan, Dim and Far is an important addition to early-twentieth-century Black intellectual history. The author indicates the significance of the ideological battle, yet complicates the debate by examining the lives of Black reformers and their shifting political allegiances. This book is evidence of the flexibility within Black politics and racial justice. “[This] book demonstrate[s] the ideological mutability of the members of the black reform community in Pittsburgh,” Cilli argues, by “[illustrating] how they developed nuanced positions toward corporate elites, the state, existing political parties, and organized labor.” Reformers in Pittsburgh were fully aware of when they had outgrown their political alliances and organizing tactics as the city’s economic, social, and political conditions changed. To take on new challenges, Black reformers were often required to adopt new ideas.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.