Mothers 4 Housing and the Legacy of Black Anti-Growth Politics

Yesterday at 6 a.m., deputies of the Oakland Police Department violently evicted an organized group of Black mothers, Moms 4 Housing, who had been squatting in a home in West Oakland owned by real estate speculators. Beginning in November, the women commandeered the house along with their children to protest the ongoing displacement of working-class Black communities by developers. Led by Dominique Walker, these women stood up not only for their progeny but also “for everyone in the Oakland community” who they claim deserve a “safe and dignified place to live.”

By refusing to leave, Moms 4 Housing staked a radical claim on the city. Despite the fact that empty housing units outnumber the homeless in Oakland, developers and politicians continue to forward the erroneous claim that speculative development will make for better, more livable cities. In reality, as these women’s ongoing protest brings to the fore, the city is protecting the rights of real estate speculators to profit at the incalculable cost wrought through the distress and trauma caused by intergenerational expropriation from the already property-less. These women’s political strategy is drawing out the contradictions: Oakland, like many other cities across the US, is willing to displace real communities for prospective future residents who have, as of yet, never materialized.

The unjust removal of Moms 4 Housing and their arrest demonstrate the ways that the paradigm of speculative growth privileges profit over the lives of displaced residents from “gentrifying” communities. This shared experience of forced removal across many US cities is of course not by happenstance. From Oakland to Philadelphia, Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITS) and other large-scale real estate managers, organized speculatively, are driving the total redevelopment of urban cores at the expense of the historical communities who sustained American cities while federal and state officials, as well as investors, disinvested from them between the 1970s and the 1990s. REITS, like those transforming Oakland and other cities, were codified legally through a rider bill on the Cigar Excise Tax Extension signed by Dwight Eisenhower in September 1960. Although not utilized at a large scale until the 1980s, since 2008 they have been a major site of investment, growing in returns and capitalization disproportionate to other markets in the aftermath of the Great Recession.1 According to the 1960 legislation, they are defined as an “unincorporated trust or an unincorporated association … (1) which is managed by one or more trustees; (2) the beneficial ownership of which is evidenced by transferable shares, or by transferable certificates of beneficial interest; (3) which (but for the provisions of this part) would be taxable as a domestic corporation; (4) which does not hold any property primarily for sale to customers in the ordinary course of its trade or business; (5) the beneficial ownership of which is held by 100 or more persons … .”

Constituted in a similar fashion to mutual funds, REITS open real estate to dispersed stockholder ownership. These corporations manage portfolios encompassing retail and residential properties as well as mortgages. The funds of traditional lenders deregulated after the 1999 Steagall Act — as well as those of mutual funds, insurance companies, and privatized retirement funds — are currently bound in tenuous urban real estate markets across the United States through speculation. Although Americans exert little democratic oversight regarding the siting, construction, or development of shopping centers, regional malls, apartments, manufactured homes, green spaces, and single family houses — or over the dispensation of commercial and private mortgages — these things are our collective assets generated from a range of sources that make us removed stockholders if also passive owners. REITS represent a form of concentrated economic power, divorced from ownership in which ordinary people are inadvertently fueling the violent reterritorialization of the urban landscape.2 The financialization of real estate and the fracturing of ownership through securities and markets buttress unilateral and undemocratic visions for the city’s future, one’s that privilege absentee shareholders over present residents.

The OPD’s predawn raid also invokes the history of similar actions to derail organized efforts by Black communities to interrupt speculation and growth at other historical junctures. In 1977 and 1978, the Philadelphia Police Department as well as Richmond, Virginia’s police department made early raids on two related organizations, MOVE and Seeds of Wisdom, who challenged the orthodoxy of growth as the solution for overlapping urban crises.

MOVE emerged in Philadelphia’s Powelton Village after 1972. Drawn together as women and men fleeing lives of violent poverty as well as humdrum and tedious labor, adherents collectively committed to the path ordained by their founder and leader John Africa. MOVE members rejected growth, actively courting the destruction of what they called the “reform world system.” MOVE’s naming of the “reform world system” announced their refusal to s pinpoint a particular agency as the singular culprit for insecurity, death, and destruction facing Black and other communities. The group viewed policing, war, pollution, and sickness as the byproducts of an interconnected assemblage animated primarily through violence and death and operating at the planetary scale. MOVE’s terminology remained capacious, drawing together under one name the various sources of violence shared between markets and state functions along a continuum from policing to development. MOVE’s growing conflict with the police between 1972 and 1978 resulted in part because of MOVE’s politics contradicting growth. According to MOVE this system organized through a commitment to cancerous growth led to radical exploitation, threatening living in the broadest sense of all forms of vital energy inhabiting earth. MOVE theorized the reform world system as entangling and colonizing all life and indicted it for creating instruments of death including bombs as well as less tangible threats like pollution with the equal capacity to debilitate and extinguish life.3 MOVE called for the radical cessation of growth and an end to capitalist and socialist paradigms that depended on the exploitation of human life and all the creatures inhabiting the biosphere.

Renouncing the violent world around them while committing to a radical vision of interspecies harmony, MOVE found itself in immediate conflict with local homeowner’s associations seeking to preserve property value as well as in indirect conflict with the area’s major land holders represented by the West Philadelphia Corporation (WPC). Composed of Drexel University and University of Pennsylvania, among other institutions, the WPC sought to transform West Philadelphia into a space that might attract and retain white middle class homeowners from the 1950s forward. Rather than seeking a solution for mounting urban problems concentrated in areas like Philadelphia’s Black Bottom, adherents of John Africa’s Law or Philosophy of Life sought to devolve the urban landscape and return it to a “natural” state. As part of their commitment to a decolonized relationship to the earth and to one another, MOVE members transformed the row house they shared into the embodiment of the “natural” world they hoped would some day displace the current one. They stripped the house it of its furnace as well as all but the barest of furnishings, and repurposed it for their spiritual and political mission of radical transformation through a respect for all living entities.

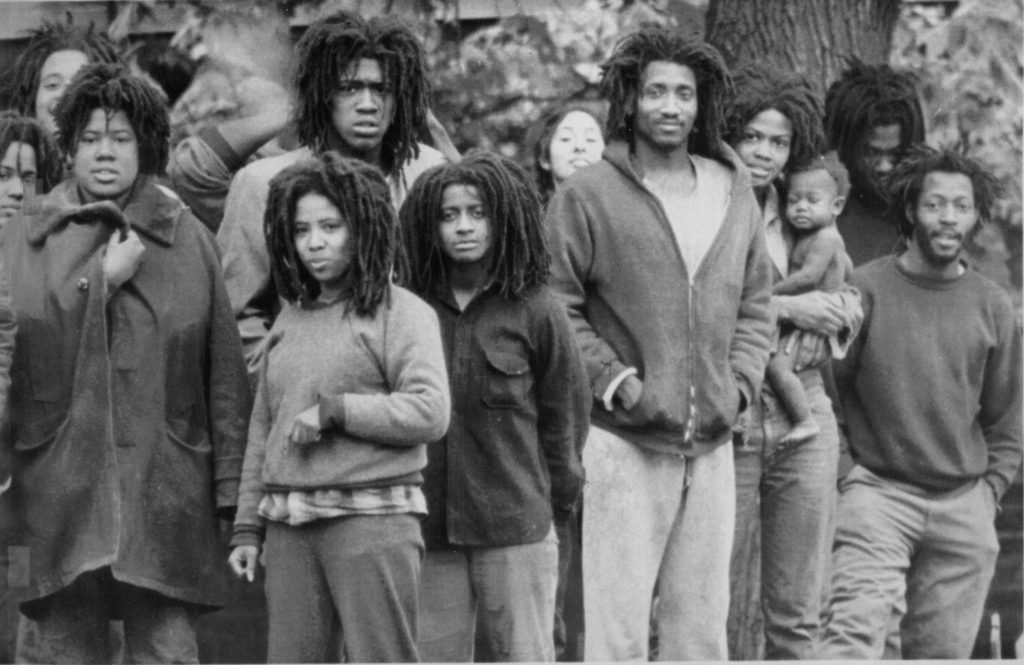

As well, women adherents, including John Africa’s biological sister Diane, and children maintained the standards for “natural living” dictated by John Africa’s philosophies as part of Seeds of Wisdom in Richmond, Virginia. Like MOVE adherents in Philadelphia, Richmond’s membership sought decolonial relationships amongst humans and with the wider biosphere. They renounced the system and engaged in a practical reimagination of their two-story stucco headquarters in Church Hill, taking it offline from the city’s electrical grid and maintaining only basic furniture and bare floors. Centering their aspirations for the future of themselves and the rest of the world in radical peace rather than in the systems binding life to destruction, Seeds of Life like MOVE practiced veganism, embraced peace in relation to other people and to other living entities, renounced the system, and removed their children from public schools in order to educate them in the teachings of their founder. Like other adherents of various Black esoteric traditions throughout the twentieth century — including the Nation of Islam, Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement, and MOVE — Seeds of Wisdom adherents also closed themselves off from the wider world socially, materially, and symbolically. In addition to the transformation of their home and the removal of their children from schools, they changed their outward appearance, donning locked hair and simple clothing. They too adopted a new surname that poignantly signified their new affiliation of family and community through their adherence to the teachings which set them apart.4 They used the common surname Life to signify their affiliation the new “law of life” and their kindredness not through blood and property but through their unique contact with and embrace of their faith in a world reimagined. Both MOVE and Seeds of Wisdom sought freedom for Black communities (and other living creatures) from what anthropologist Julie Livingston calls in a different context “self-devouring growth” to describe regimes of economic expansion that ultimately imperil human existence. As followers of a Vietnam veteran who had experienced firsthand the carnage of American empire, MOVE and Seeds of Wisdom were determined not to kill another sentient life form except in self-defense.

MOVE members’ attempted to protect their children from forced dislocation from their home in Philadelphia by sending them to live with Seeds of Wisdom in the midsts of the PPD’s siege of their home in 1977 and 1978. The children still faced violent separation in Richmond. In an attempt to arrest Diane and Valerie Africa for supposed child neglect, Richmond Police faced off with the five women and fourteen children living at the Churchill headquarters. Diane and Valerie, like the women of Mothers 4 Housing refused to leave or to allow the state entry into their space. Stemming from allegations of malnutrition, and specifically protein deficiency attributed by public health pediatrician Arlene Mayer, Richmond police surreptitiously raided the home at 1:30 a.m. on August 8 in order to take those inside off guard. At that time they confiscated all fourteen children, placing them in the city’s foster care system, despite later evidence that the children were nutritionally and otherwise healthy. Later in 1978, police also raided MOVE’s Philadelphia headquarters, sparking the smoldering tensions between the group and the city that exploded in the PPD and ATF’s reckless 1985 bombing of MOVE’s compound in Cobbs Creek that killed eleven members and burned dozens of adjacent homes.

MOVE and Seeds of Wisdom, as well as the contemporary efforts of Moms 4 Housing, represent both the powerful legacy of and the dangers of embracing the Black anti-growth political tradition. Across varying regimes of growth common sense, Black political organizations of various stripes have staked the claims of Black well-being over and against the desire for unchecked profit for real estate and other capitalist interests, claiming the bonds of family, organization, and community above the unsustainable edicts of perpetual growth. This is a legacy we must recall as we face the ongoing displacement of Black urban communities and the threat of unchecked growth regimes on the collective future.

I stand with Mothers 4 Housing and all of those fighting to ensure that everyone has, in the words of Dominique Walker, “a safe and dignified place to live.”

- For an account of the rise of Real Estate Investment Trusts in the context of ex-urban development, see Elizabeth Blackmar, “Of REITS and Rights: Absentee Ownership at the Periphery” in City, Country, Empire: Landscapes in Environmental History, ed., Jeffry M. Diefendorf and Kurk Dorsey, (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005) ↩

- For an influential and important interpretation of the emergence of modern corporations defined by dispersed ownership and concentrated power, see Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World Company, 1932); For Berle’s extension of this into an important critique of mutual funds (and by extension contemporary REITS), see Adolph Berle, Power Without Property: A New Development in American Political Economy, (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1959) ↩

- For example, see the testimony of Eddie Africa and others during the 1981 trial of John Africa in Philadelphia. Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission (MOVE) Records, Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries. ↩

- Harold Jamison, “MOVE sees conspiracy to take kids,” Philadelphia Tribune, Oct. 7, 1980: 15. ↩

A perfect historicization.