“More Than Words or Ideas But Life Itself:” Cedric Robinson’s Testament

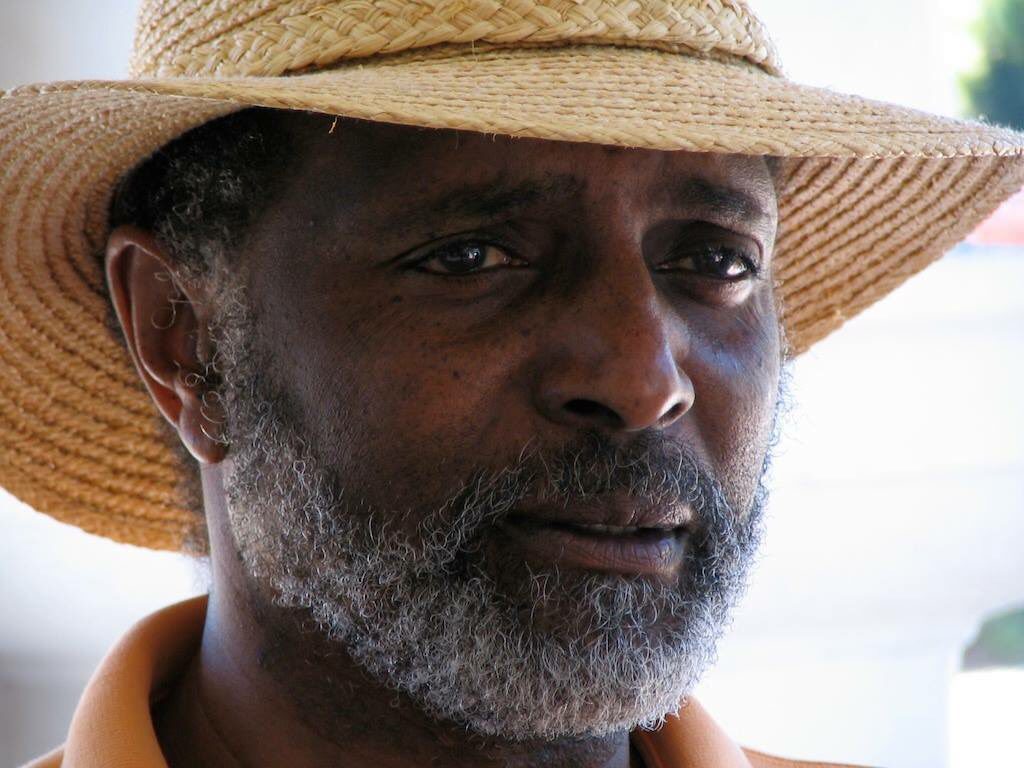

Today we continue to honor the life and legacy of Professor Cedric Robinson who passed away earlier this week. Dr. Robinson was a beloved scholar and mentor who authored several foundational texts including Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition and Terms of Order: Political Science and the Myth of Leadership and Black Movements in America. In today’s post, Dr. Josh Myers reflects on the significance of Dr. Robinson’s research on the black radical tradition.

***

The world shines a little dimmer today. We will miss Cedric Robinson, a towering intellectual who taught us to think imaginatively and expansively about the forces of racial capitalism and the ferocity of the Black radical tradition. Professor Robinson helped to develop our Center for Black Studies, serving as Director from 1978 to 1987. We extend our condolences and love to Elizabeth and Najda and to all those in Cedric’s orbit, those close and those far who were profoundly influenced by his fierce intellect, political commitments, and humanizing ways.

— Diane Fujino, Director, on behalf of the Center for Black Studies Research

***

If this were a different age, an age where deep literacy reigned, where Black ideas truly mattered, Cedric J. Robinson’s transition to ancestry would have occasioned a collective pause. But because he studied, wrote, and devoted his life to a tradition of struggle without seeking the trappings of fame, he is one for the ages–all ages. In the best traditions of scholarship, our indigenous knowledge systems, the duty of the thinker (“those who know”) is to speak by connecting to our past and to the future in a simultaneous narrative and conceptual thread. In doing so, the thinker evokes the idea that we are all we have been and all we will be.

The Black Radical Tradition, so artfully examined and explained by Cedric Robinson, is us, all we have been, and all we will be—must be. So I am encouraged in this moment that his work will never occupy the dustbin of forgotten ideas, for he did his work in such a manner that it necessarily has to be engaged. It is unavoidable. It is as necessary to scholarship and struggle as the work of W.E.B. Du Bois, Claudia Jones, and Paul Robeson, because it came directly from their tradition of sacrifice. Cedric Robinson was like them, a movement veteran, but a thinker, an exemplar of the idea that these are not separate. And like them he will never be forgotten.

I was not personally close to Cedric Robinson. Yet the one time we met, he offered words of encouragement (and a homework assignment). He was of gentle character–what the Yoruba call iwa pele. Though I met him later in my own development, his written words have been with me in my teaching, writing, and thinking from the beginning. It is like he was there all along. I felt an intellectual and an epistemological closeness that was unlike many other scholars whose work I had read.

He was not simply a curious academic, willing to trade stories of our struggle for the relative comfort of academic licensure and the security of tenure. After all, none of us are truly secure until all of us are free. Robinson’s work shows us that the terms under which we struggle for our daily existence are the very terms that enable the continued destruction and devaluing of life in global modernity. Robinson’s ideas show us that freedom is the ability to self-determine—to think on one’s own—the kind of world we want to inhabit. Robinson’s contributions show us that “theory” is the preserve of those who are brave enough to struggle, to constitute themselves as the arbiters of their fate.

As the preface to his tour de force, Black Marxism revealed, his intellectual work came directly from his engagement with “our people’s struggle,” on the ground, in the community. That is, his intellectual work was the product of real sacrifice, authentic commitment, and revolutionary love. Therefore it is no mistake that the result was an idea that was always already there, waiting for us to re-member it, to rekindle—as Haile Gerima is fond of saying—those embers that lay undisturbed under the ashes of last night’s fire.

The Black Radical Tradition was not discovered, it was simply uncovered for us, whose eyes had been blinded by the belief that revolution had to have come from some other place, some other time, some other people. It was always already there, because our ancestors, the earliest exemplars of the Black Radical Tradition, were those Africans who resisted this world so that another one would be possible. Cedric Robinson has ensured that we will never forget that again.

Josh Myers is an Assistant Professor of Africana Studies in the Department of Afro-American Studies at Howard University. In addition to serving on the board of the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations and the editorial board of The Compass: Journal of the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations, he works with the DC area collectives, Positive Black Folks in Action and the Nu Afrikan Cultural Vanguard. His research interests include Africana intellectual histories and traditions, Africana philosophy, critical university studies, and disciplinarity. His work has been published in The Journal of African American Studies, The Journal of Pan African Studies, The African Journal of Rhetoric, The Globalization and Human Rights Law Review, Liberator Magazine, and Pambazuka, among other literary spaces. His current book project is a history of the Howard University student protest of 1989. He blogs at http://speaktomekhet.

I studied with Cedric Robinson when he was teaching at SUNY-Binghamton, while he was working on what would eventually become “Black Marxism”. In fact, that was the title of our seminar. He was a strong and gentle soul and a powerful, committed scholar. His reading of Richard Wright / Cross Damon endures, and I still relish the memory of the discussion he provoked. May he rest peacefully. I’m forever grateful for his teaching.

In my 35 years as Cedric’s colleague I always admired the fact that he understood that campus progressives work in many ways — that the struggle had many fronts. As a result, he was never judgmental or self-serving. ‘Grace’ is the word that comes to mind. I will miss him.