Mickey Leland and Africa in American Politics: An Interview with Benjamin Talton

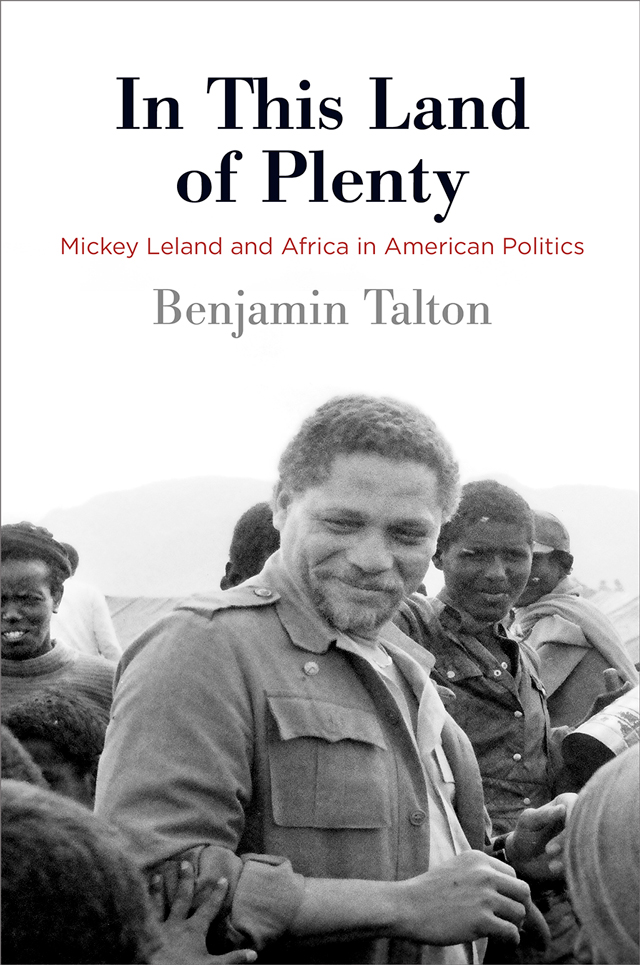

In today’s post, AAIHS President Keisha N. Blain interviews Benjamin Talton, an associate professor of History at Temple University, about his new book, In This Land of Plenty: Mickey Leland and Africa in American Politics (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019). Dr. Talton is a graduate of the University of Chicago and Howard University. In addition to his most recent book, In This Land of Plenty, he is the author of Politics of Social Change in Ghana: The Konkomba Struggle for Political Equality (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). He is an editor of African Studies Review and serves on ASWAD’s executive board. Follow him on Twitter @benjamintalton.

Keisha N. Blain: You’ve written what I believe to be the first book on Congressman Thomas “Mickey” Leland. In your introduction, you mentioned being captivated by his life — and stunned by his untimely death in 1989 — when you were only 15 years old. Tell us more about your interest in Leland and the circumstances that led to your decision to write a book on his political career.

Benjamin Talton: From the moment I learned about Mickey Leland in August 1989, his life story captivated me. He had already died when I heard his name for the first time in a breaking news story, but I did not know that yet. As I watched the television news coverage of the joint US-Ethiopian search for the missing plane that was carrying Leland and his delegation to a refugee camp in southeastern Ethiopia, I was rapt. The coverage showed Leland during his frequent trips to Africa, in villages, meeting with heads-of-state, and at feeding centers during Ethiopia’s historic famine. At the age of 15, I was awestruck by the sight of a congressman who looked, spoke, and acted in ways similar to the African-centered activists I had grown to admire. And while I was familiar with the Congressional Black Caucus’s (CBC) activism against apartheid in South Africa, I soon learned that Leland pursued a much broader Africa agenda, and that impressed me.

Twenty-five years later, as a professor of African history, I began to reflect upon the palpable absence of Africa, literally and figuratively, in African American politics, and the significant price we pay as a result, because foreign affairs was an entry point for an African American agenda, international engagement, and moral leadership. I see Leland’s political story as a way for us to understand the forces that imbued Africa with cultural and political significance for African Americans during the 1970s and 1980s and why it ceased to have comparable meaning in subsequent decades.

Blain: Your book makes significant contributions to various fields of study and several subfields within US and global history. Tell us more about the book’s contributions specifically to the literature on Black radicalism and Black internationalism. How does your book build on prior works yet also expand our understanding of these topics?

Talton: I consider one of the book’s central contributions to be that it shows African American elected officials integrating the ideals of Black internationalism and Global South solidarity — ending white-minority rule in southern Africa, dismantling Cold War policies toward leftist governments, and, especially for Leland, using America’s resources for Africa’s economic benefit — into mainstream US politics. I also examine the important ways that US, Ethiopian, and South African politics intersected and shaped each other throughout the 1980s.

To develop my analysis, I drew from a rich body of scholarship on transnational activism and organizing during the twentieth century, most notably by Penny Von Eschen, Brenda Gayle Plummer, Gerald Horne, and Robin Kelley. My book helps bring the scholarship into the 1980s and brings events and political actors in Africa to the fore.

I also suggest that the late 1970s and 1980s were a distinct political period, particularly given our community’s increased access to and use of the ballot, and the growing sway and subsequent economic and political challenges created by Reaganomics and Thatcherism. I’m convinced that if we fold the period into the 1960s and early 1970s as “post-Civil Rights,” as is common in much of the scholarship, we erase the political and cultural dynamism that mark it as a critical inflection point in transnational, US, and, specifically, African American histories.

I also set out to demonstrate in the book that Black internationalism and Black radicalism were not necessarily dissonant with electoral politics. Leland’s activism and political career show electoral politics as a logical choice for young radical activists of the time, among the array of necessary tactics toward building a more just and equitable world.

Blain: One of the arguments you make in the book is that Leland is “emblematic of the afterlife of international radicalism in the United States” (p. 3). How is that the case? How would you situate Leland within the constellation of Black internationalist radicals of the twentieth century, including well-known figures such as C.L.R. James, Claudia Jones, and Angela Davis? To what extent did Leland build on their work, and in what ways did his activism and ideas represent a departure from earlier activists and intellectuals?

Talton: You named Black internationalist icons. I am confident that Leland would eschew efforts to place him in such esteemed company, although he and Angela Davis were born the same year. I continue to be attracted to Leland as a biographical story and as a political figure, apart from his commitment to Africa and humanity, because — as he would have put it — he was a “sideman of history” who tried to turn some of the central tenets of Black radical politics, anti-imperialism, anti-racialism, and protecting the sovereignty of Global South nations, into policy. He and his colleagues animated these goals in Congress and fundamentally altered US relations with South Africa, Ethiopia, and Nicaragua, specifically, but generally elevated Africa within US foreign policy. Although he was not successful, Leland sought to make similar progress with US relations with Cuba, Mozambique, and Vietnam.

These initiatives, as I argue, were emblematic of the afterlife of international radicalism. The Third World, or Non-Aligned Movement, had failed to meet its expectations, and the international left had all but dissipated. Yet, Western neoliberalism was ascendant by the 1980s. The flashes of leftist radicalism, such as the CBC’s anti-apartheid activism, Thomas Sankara’s revolution in Burkina Faso, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, Maurice Bishop’s Jewel Revolution in Grenada, among others, came out of governments rather than from political theorists and grassroots movements.

To return to your question, at first glance it’s natural to place Leland and his CBC colleagues as part of a political genealogy that runs through the icons of anti-imperialism from within Western-governing bodies, like Ralph Bunche at the United Nations and Andrew Young as US representative to the UN. But I argue that Leland followed in a tradition of organization and institution building in the US aimed at African liberation and Global South solidarity that included the Council on African Affairs (CAA), during the 1940s and 1950s. Leland’s contemporaries Prexy Nesbitt, Sylvia Hill, and Robert Van Lierop carried this movement forward in the late 1960s and early 1970s, before Van Lierop and Hill broke from the American Committee on Africa (ACOA) to form the African Information Service (AIS). To be clear, other organizations animated the internationalism of the period as well, including the Black Panthers, SNCC, the NAACP, and the National Council of Negro Women. But the CAA, ACOA, AIS were among the organizations dedicated specifically to raising awareness of African issues within the US, promoting and supporting African liberation movements, and lobbying for radical change to US foreign policies toward Africa that laid the groundwork for African American political strength within Congress during the 1980s.

But it was Congressman Charles Diggs, while he worked closely with an array of pan-Africanist and other Black radical figures and organizations, who brought Black internationalist and Third World goals into Congress and pursued them through activism from the inside, founding the Congressional Black Caucus, and establishing the foundation for what would become TransAfrica. I cast Leland as the one who took up Diggs’s mantle of leadership on African affairs in Congress, until his death in 1989.

Blain: As you point out in the book, Leland was certainly not the first radical (and internationalist) activist to engage African issues or lead humanitarian efforts and support freedom struggles in places like Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Africa. Yet Leland, with support from his colleagues in the Congressional Black Caucus, was able to accomplish several goals as a US congressman that set him apart from earlier activists. Tell us more about those political gains and why they were especially noteworthy during the Cold War period.

Talton: It’s difficult to categorize Leland and his colleagues’ political initiatives as gains and losses. They sought to achieve certain discernible political benchmarks, but they also regarded initiatives to change their colleagues and the public’s perceptions of issues in Africa, the Caribbean, and the African American community as critical. I don’t devote much space to it in the book, but it is worth noting that the CBC annually issued an alternative budget, which was people-centered and privileged social justice issues. Their budget was not debated in Congress, but it drew public attention to the deficiencies in Reagan’s budget. I do write in detail about Leland’s delegations to Africa, which he used to raise awareness of issues on the continent. He and his colleagues also organized protests in response to specific legislative issues; trade sanctions on the South Africa government were the most prominent among them. But there were many others, including Reagan’s illegal invasion of Grenada, homelessness, and the president’s cuts to federally funded social programs.

Leland achieved a more tangible gain when he lobbied successfully in 1984 for a Select Committee on Hunger. He served as its founding chair until his death. As a select committee, the Hunger Committee could not introduce legislation, but Leland held hearings, commissioned research, and submitted reports and recommendations. His initiatives were critical to shaping the narrative within Congress on hunger and poverty in the US and Africa, and made him and his committee central to policy debates in the era of increasing austerity toward people-centered policies, such as education, healthcare, public infrastructure, and housing. He also leveraged his position to highlight the effects of the Reagan administration’s austerity measures and to undermine the president’s claim to hold the moral high ground in the Cold War.

Again, what sets Leland’s activism apart from others of his generation was that, using foreign affairs as a vehicle, he modeled radical, African-centered activism from within the US government, laying the groundwork for transformative Black diasporic liberation work and transnational solidarity that has never been fully realized. He coupled these with the humanitarianism heavily influenced by and forged in Works of Mercy, championed by Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement.

Blain: Tell us more about your experience doing research for the book. You’ve weaved together a diverse array of sources, including archival collections, congressional records, newspaper articles, and interviews with Leland’s relatives and friends. What sources did you find especially useful? What challenges did you encounter during the research process?

Talton: I enjoyed the experience of conducting research for this book. It took longer than I initially anticipated, but I learned a great deal and met many really wonderful archivists, librarians, present and former activists, and politicians. For my first book, I spent most of my time in a small archive in northern Ghana and conducting oral interviews in small villages along Ghana’s border with Togo. While I did travel for research to Addis Ababa, Mekele, and Lalibela in Ethiopia for In This Land of Plenty, I conducted most of the research at university, presidential, and municipal archives in the United States. These places were all, without exception, a joy to visit and work in.

The challenges for me came during the writing process. I made the conscious choice to build my analysis of otherwise disparate themes and events around the narrative of Leland’s political growth and the contours of his political career. My goal was to have a study and a story that would speak to multiple fields and be truly transnational. So I drilled down on issues and events in Ethiopia, for example, and on background to South Africa’s domestic anti-apartheid movement, and I found that the Leland thread was getting lost. So, part of the challenge was to balance developing the African and US sides of the story, while keeping Leland at the center. He was involved in so many international issues, and I was concerned that I might either over- or under-contextualize and analyze them. But I see this as the exciting risk one takes when writing truly multi-archival and multi-national histories.

Blain: Many people know Congressman “Mickey” Leland largely because of his humanitarian efforts and commitment to eradicating hunger. Your book does an excellent job of charting his intellectual journey — including the moments he shifted his views and approaches — and capturing the full extent of his political commitments. What do you hope readers will take away from reading the book? How would you summarize Leland’s legacy?

Talton: I hope I have fulfilled my mission in writing this book, which was, in large part, to tell the story and provide some analysis of Africa’s prominence in African American politics and popular culture during the 1980s. I also hope that readers recognize, through Leland’s activism and career in the Texas legislature and the US Congress, the amalgam of strategies involved in social justice, human rights, and humanitarianism. Leland and colleagues of his generation operated consciously and intentionally as people of African descent, inextricably bound to peoples in the Caribbean and Africa.

From Mayor Richard Hatcher in Gary, Indiana; Mayor David Dinkins in New York; to a coterie of congressional leaders, including Charles Diggs, Ronald Dellums, Charles Rangel, Donald Payne Sr., Barbara Lee, and, of course, Mickey Leland, African American elected officials continued the long tradition of African American politics reaching beyond US borders, but they did so from within a powerful western government. Leland’s story is not well known, and I hope the reader will find his history and legacy to be as engaging and enriching as I have.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I am an Ethiopian and was a little boy when the news of the crash surfaced and clearly remember how the people I know got shocked with the news. I still have the sound of the gigantic aircraft that was landing at bole airport 10 kilometers away from the place I grew up. Later we heard that was Hercules, came in for a search mission.

The military government of the time, which always demonizes America, didn’t take time to react and open all doors of collaborations. I always think the incident had an impact on the policy of socialist leaders of the country at least changing their perspectives towards the U.S. even during the cold war time. This, I believe worth a thorough study.

I am glad to see some people are still talking about Congressman Leland even after 30 years of the incident. There were other passengers perished together with Congressman Leland in the accident and they will remain heroes to Ethiopians and to humanity in general.