Men without Pants: Masculinity and the Enslaved

Although nearly fifty-seven years have passed since Stanley Elkins’ provocative thesis on the effects of slavery rocked the historical community, scholars are still grappling with some of the basic premises he put forth. While the effects of slaveholders’ psychological terrorism still inspire intense debates, it should prove helpful for scholars to focus on how severely the enslaved were mentally tortured. Perhaps one of slave owners’ more innovatively cruel strategies concerned the ways they sought to completely emasculate enslaved boys and men—by denying them the right to wear pants. By forcing young African American boys and men to wear dress-like shirts, the owners of flesh attempted to feminize and humiliate enslaved males on a daily basis. According to scores of interviews with the formerly enslaved, denying black boys and young men the right to wear pants was a relatively widespread practice throughout the Deep South.1

This custom certainly becomes even more interesting when slaveholders’ beliefs about slave breeding and the virility of young “bucks” is taken into consideration. Countless owners commented time and again in diaries and letters about the supposedly highly-sexualized nature of young black men, and the emasculation of the enslaved must have allowed slaveholders some type of psycho-sexual superiority complex. By feminizing African American males, slave owners likely reassured themselves that they were the most masculine men on the plantation, which could be demonstrated, of course, by the rape and sexual abuse of enslaved women and girls.

Unsurprisingly, the practice of withholding pants seemed to occur commonly on large plantations, where the concentrated number of slaves required constant surveillance and discipline. Richard Orford, enslaved as a young boy in Georgia, remembered, “The children wore a one piece garment not unlike a slightly lengthened dress. This was kept in place by a string tied around their waists.” Another Georgian described it similarly, claiming “The one little cotton shirt that was all children wore in summertime then weren’t worth talking about; they called it a shirt but it looked more like a long-tailed nightgown to me.” Ed McCree concurred. “Summertime us children wore shirts what looked like nightgowns. You just pulled one of them slips over your head and went on cause you was done dressed for the whole week, day and night.”2

On some plantations boys wearing shirt-dresses were finally supplemented with pants during the coldest part of winter. “Boys wore plain shirts in summer,” Addie Vinson recalled, “but in winter they had warmer shirts and quilted pants.” Similarly, Jefferson Franklin Henry reported, “In summer boys wore just one piece and that looked like a long nightshirt. Winter clothes was jeans pants and homespun shirts.” One man raised on a Texas plantation said that all enslaved children wore “the straight-cut slip. They give the lil gals the slip dress and lil panties. In wintertime they give the boys the lil coat and pants and shoes, but no drawers or underwear.”

Yet not every enslaved male was lucky enough to receive pants when the weather turned cooler. Harrison Beckett pointed out the precariousness of the situation: “The way they dress us lil nigger boys then, they give us a shirt what come way down between the knees and ankles. When the weather was too cold, they sometimes give us pants.”3

Indeed, some of the enslaved were not even allowed pants during the freezing winters. Charlie Hudson explained that in “Winter time they give children new cotton and wool mixed shirts what come down to their ankles. By the time hot weather come the shirt was done wore thin and shrunk up and besides that, we grew enough for them to be short on us, so we just wore them same shirts right on through the summer.”

Still, regardless of whether or not enslaved boys received winter pants, they realized that there was no gendered difference in the clothes. As Will Sheets put it, “Gals and boys was dressed in the same way when they was little chaps.”4

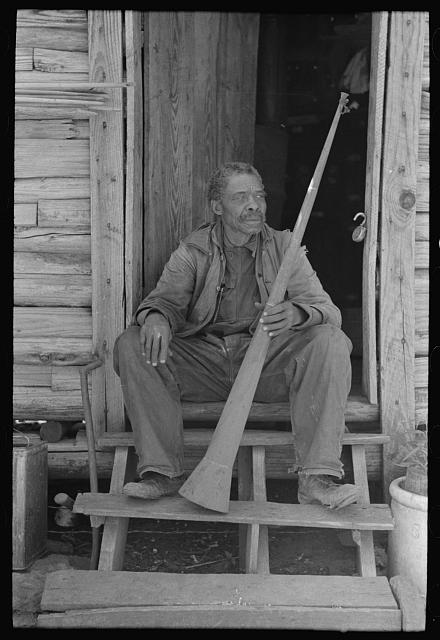

c. 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Perhaps the most psychologically damning aspect of denying boys and young men pants was the age at which they were finally granted the garment. During the mid-nineteenth century children matured very early, and boys were often drinking alcohol and becoming sexually active as young teenagers. It seems that many slaveholders withheld the privilege of wearing pants well past the point that boys were acting like young men, courting girls and trying to establish their masculine identity. Peter Ryas did not receive a pair of pants until he was ten years old; Ben Kinchlow of Texas and G.W. Hawkins of Arkansas were around twelve. Stearlin Arnwine painfully remembered wearing “my first pants when I was fourteen years old, and they stung till I was miserable…It was what we called dog-hair cloth.”5

More troubling still were the accounts of young black men being forced to wear the shirt-dresses until they were fully grown. “For the boys from five to fifteen years old, they would make long shirts out of this cloth,” one man remembered, and “No young fellow wore pants until he began to court.” Jerry Boykins, enslaved in Georgia, claimed that he “wore home weaved shirts until I was grown, then I had some pants and they were homemade, too.” Pricilla Gibson commented that “little boys wore long-tail shirts, with no pants till they’s grown.” Another man from South Carolina recalled that he “was a big boy grown when I get my first pants.”6

The long-term psychological effects wrought by denying these men pants may never be fully known. No doubt the embarrassment and humiliation caused many of the enslaved untold worries over masculinity and identity. Yet at least in some cases, African American males did not allow their deprivations to temper their activities. As Mary Johnson reported, “My brother Robert was a powerful big boy and he wasn’t allowed to have no pants until he was 21 years old, but that didn’t discourage him from courting the gals. I try to tease him about going to see the gals with that split shirt.” Indeed, Robert did the best that he could with what he had been given—but it was likely not as easy for the countless others who suffered under the psychological cruelties of the slaveholders.7

Keri Leigh Merritt is a historian of the 19th-century American South who works as an independent scholar in Atlanta. Her first book, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South, will be published in 2017 by Cambridge University Press. Follow her Twitter @kerileighmerrit.

- Stanley M. Elkins, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959); all slave narratives cited in this article appear in George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (Westport, CT.: Greenwood, 1972–79). ↩

- Richard Orford, The American Slave, Vol. 4 (GA), Part 3, 154; William McWhorter, Ibid., Vol. 4 (GA), Part 3, 95; Ed McCree, Ibid., Vol. 4 (GA), Part 3, 60. ↩

- Addie Vinson, Ibid., Vol. 4 (GA), Part 4, 102–3; Jefferson Franklin Henry, Ibid., Vol. 4 (GA), Part 2, 183; Chris Franklin, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 2, 56; Harrison Beckett, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 1, 56, italics mine. ↩

- Charlie Hudson, Ibid., Vol. 4 (GA), Part 2, 224; Will Sheets, Ibid., Vol. 4 (GA), Part 3, 239. ↩

- Peter Ryas, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 3, 275; Ben Kinchlow, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 2, 264; G.W. Hawkins, Ibid., Vol. 2 (AR), Part 3, 216; Stearlin Arnwine, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 1, 33. ↩

- J.W. Whitfield, Ibid., Vol. 2 (AK), Part 7, 138; Jerry Boykins, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 1, 122; Pricilla Gibson, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 2, 67; Sabe Rutledge, Ibid., Vol. 14 (SC), Part 4, 65. ↩

- Mary Johnson, Ibid., Vol. 16 (TX), Part 2, 220. ↩

I’m reminded of Chapter V of Frederick Douglass’s 1845 *Narrative:* “I was kept almost naked–no shoes, no stockings, no jacket, no trousers, nothing on but a coarse tow linen shirt, reaching only to my knees. I had no bed. I must have perished with cold, but that, the coldest nights, I used to steal a bag which was used for carrying corn to the mill. I would crawl into this bag, and there sleep on the cold, damp, clay floor, with my head in and feet out. My feet have been so cracked with the frost, that the pen with which I am writing might be laid in the gashes.”

When I teach this passage I note how far this passage travels, from “almost naked” to the pen held by Douglass at the moment of writing, with which he exerts mastery and authority over the story of his life.

Absolutely! So much more could be written on this topic. Thank you so much for sharing. Enjoy your Sunday.

Did Africans before the European encounters wear pants?

The weather aloud them not to have to wear pants but they had the freedom to choose.

Excellent reply.

Africans were wear clothes when your ancestors were still painting themselves blue and living in caves.

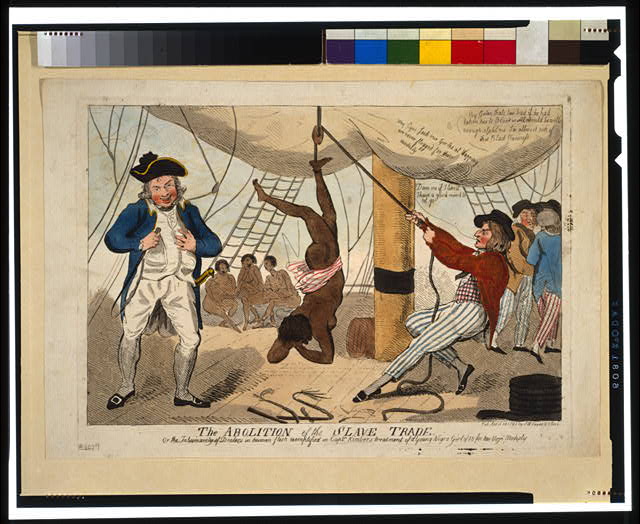

Let’s not forget

Never

You are so right let us never forget never never never

The vast majority of whites during this era were horrible, brutal savages. Whites thieved, raped, pillaged, brutalized, disenfranchised, enslaved, and culturally annihilated countless Africans. A startling number of modern whites are still of the malignant cancer stock that their ancestors were made of. The largest problems of the world can be attributed to their ilk. Clearly the most disappointing race to ever disgrace the Earth. Funny how they tell Blacks in America to “leave”, “get over it”, “stop playing the race card”, and “go back to Africa”……but they’re not even from here. A truly sickening and vomit-inducing race. I feel for my ancestors who had to suffer the foul atrocities of the whites. I will honor you by being better than those subhuman monsters. #NotHate #JustTruths #BlackLivesMatter #IgboKwenu

It wasn’t a majority of whites that were slave masters, or the slavery wouldn’t have ended. Lots of people knew this was deplorable and made sure it stopped.

North Africa also enslaved Europeans. Slavery is a barbaric act that does not belong to one race. America also had enslaved the irish but the sun burns would literally kill them in the fields. Which is why they switched to heavily melanated beings.

Slavery in the US was based on race unlike in other places. And the aftermath of slavery was also quite cruel and odious–segregation, lynching, Jim Crow laws, Constitutional designation as less than human, disenfranchisement and on and on. One should make no excuses for American slavery or try to lessen the evil of it by stating slavery happened elsewhere. It’s a blight on the country’s history that needs to be acknowledged, at the least.

Yessss the worst of worst on the face of Earth. How can I forget thet tortures my ancestors suffered. If there is terrorist coming to the country they’re coming to torture the white man.

“But can a people live and develop for over three hundred years simply by reacting? Are American Negroes simply the creation of white men, or have they at least helped to create themselves out of what they found around them?” – Ralph Ellison, SHADOW AND ACT (1964)

If only African Americans could only see how important it is to know we need each other.