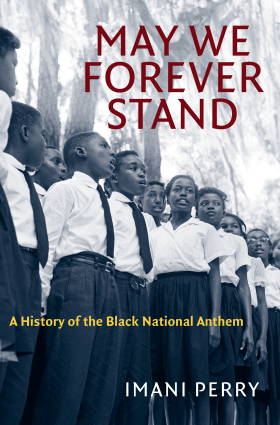

May We Forever Stand: A New Book on the Black National Anthem

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem was recently published by the University of North Carolina Press.

***

The author of May We Forever Stand is Imani Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University where she also holds affiliations with the Program in Law and Public Affairs and Jazz Studies. She is the author of three books: Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Duke University Press), More Beautiful and More Terrible: The Embrace and Transcendence of Racial Inequality in the US (New York University Press), and May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem (University of North Carolina Press). She has two books forthcoming in September of 2018: Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry (Beacon Press), and Vexy Thing: On Gender and Liberation (Duke University Press), and numerous articles in the fields of legal history, cultural studies and literary studies. Follow her on Twitter @imaniperry.

The author of May We Forever Stand is Imani Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University where she also holds affiliations with the Program in Law and Public Affairs and Jazz Studies. She is the author of three books: Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop (Duke University Press), More Beautiful and More Terrible: The Embrace and Transcendence of Racial Inequality in the US (New York University Press), and May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem (University of North Carolina Press). She has two books forthcoming in September of 2018: Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry (Beacon Press), and Vexy Thing: On Gender and Liberation (Duke University Press), and numerous articles in the fields of legal history, cultural studies and literary studies. Follow her on Twitter @imaniperry.

The twin acts of singing and fighting for freedom have been inseparable in African American history. May We Forever Stand tells an essential part of that story. With lyrics penned by James Weldon Johnson and music composed by his brother Rosamond, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was embraced almost immediately as an anthem that captured the story and the aspirations of black Americans. Since the song’s creation, it has been adopted by the NAACP and performed by countless artists in times of both crisis and celebration, cementing its place in African American life up through the present day.

In this rich, poignant, and readable work, Imani Perry tells the story of the Black National Anthem as it traveled from South to North, from civil rights to Black power, and from countless family reunions to Carnegie Hall and the Oval Office. Drawing on a wide array of sources, Perry uses “Lift Every Voice and Sing” as a window on the powerful ways African Americans have used music and culture to organize, mourn, challenge, and celebrate for more than a century.

“This moving history will inspire all readers, but particularly those for whom ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ is a profound touchstone.”–Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor, Harvard University, and host of ‘Finding Your Roots’

J.T. Roane: Books have creation stories. Please share with us the creation story of your book—those experiences, those factors, those revelations that caused you to research this specific area and produce this unique book.

Imani Perry: The origin of this book isn’t neat. It unfolded over 8 years. There were moments that beckoned me to it, some of which I share in the book like when my five year old son unexpectedly came home singing it. Or my fascinated and emotional response to Reverend Lowery reciting the words in his benediction for President Obama’s first inauguration. But more than anything, it was born of a deep desire to narrate an aspect of Black life that I believe had been given too short a shrift in academic scholarship: the formal ritual practices that thrived behind the proverbial DuBoisian veil.

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” is not just a song that endures and is beloved, it is a song that grew to its stature in the midst of the rich fabric of civic associations, political actions, and social life in Black communities and particularly in the Black South. I refer to all of this as “Black Formalism,” and I describe the singing of the anthem as a key feature of Black formalism. In writing this book, I wanted to bring this world to the scholarly record, with a particular commitment to showing that 1) Black formalism and the associational life that was a part of it were central to Black working class life, and not primarily the province of elites; 2) These practices provided an essential foundation to the mid-twentieth century freedom movement; they built freedom fighters; 3) School rituals and curricula were critical sites for the political development of Black youth; 4) The anthem sat within an international Black political consciousness that has often been submerged in our accounts of Jim Crow living; and 5) Black formalism should be distinguished from the “politics of respectability.” While the politics of respectability used adopting ideals of middle class respectability as an argument for the full inclusion of African Americans in the fabric of society, Black formalism was internally focused. It was about building a world of meaning ritual and dignity, notwithstanding the violence and exclusion of Jim Crow.

Finally, this book was, like all of my scholarship, a methodological exercise and experiment. I continue to grapple with how we who work in African American studies must sharpen or refashion the tools we are trained with in order to robustly capture aspects of Black life that don’t fit neatly into the way things tend to be accounted for in the disciplines. For this book, graduation programs, op-eds, novels, plays, memoirs, political protests, school curricula, and the records of civic and professional organizations were all necessary to build the story. I had to build my own archive, guided by what I knew from my communities. Finding the sweet spot between understanding the importance of community-based knowledge and rigorous academic methods of inquiry is an ongoing responsibility of the scholar of Black studies.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.