Making ‘A Nation Within A Nation’: An Interview with Komozi Woodard

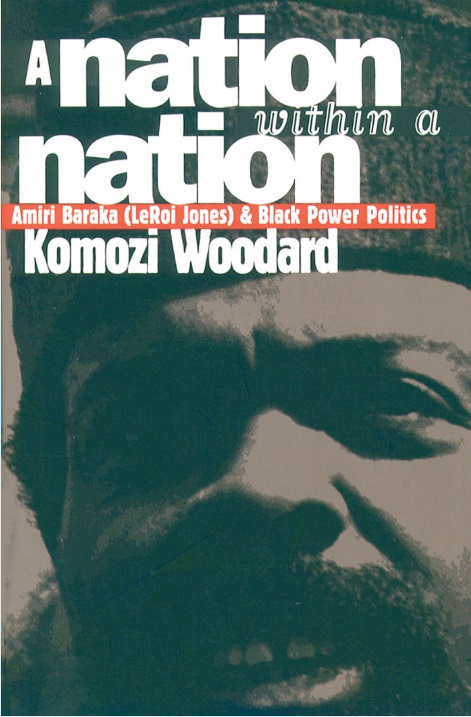

*This post is part of our online roundtable celebrating the 20-year anniversary of the publication of Komozi Woodard’s A Nation Within a Nation

In today’s post, Say Burgin, Assistant Professor of History at Dickinson College and this online forum’s organizer, interviews Komozi Woodard about his book A Nation Within A Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics. Burgin, a historian of the 20th-century US who focuses on social movement and African American history, uses this interview with Woodard to highlight his book’s important contributions to Black Power history and obtain insight on his journey and thought process during researching and writing it. This interview concludes our online forum celebrating the 20-year anniversary of the publication of A Nation Within A Nation.

Say Burgin: What were some of the pressures you faced when you started to do dissertation research on Black Power in Newark?

Woodard: When I proposed to do the topic, Bob Engs at the University of Pennsylvania wanted me to do his topic. He was an expert on Reconstruction in Virginia, and so he wanted me to do part two of what he was doing! And you know, as gracefully as I could, I said, “That’s a wonderful topic but—you know—I’ve already interviewed fifty or sixty people.”

Burgin: So you had interviewed people before you got to the PhD program at the University of Pennsylvania?

Woodard: Yeah, what happened was I was running Children’s Express, and [Newark tenant activist] Takalifu said, “Why don’t you write our history?” And I told her that I didn’t have most of the documents. And so she said, “Come to my apartment.” So I followed her to her apartment … she went underneath her bed and pulled this beautiful box out—you know handcrafted—and she opened it up, and it had the [Black Power] pamphlets and posters, and she said, “Start with this.” So with that, it reminded me…it wasn’t just my history, but the people in the community cherished this history, and they wanted a record of it. So I used the Children’s Express method of doing the interviews [with former Black Power activists in Newark]; I had children conduct the interviews with me. So, when I give them acknowledgement, those two students—Nicole Morris and Vanessa Whitehead—did most of those interviews with me.

Burgin: What was it like to have children doing those interviews?

Woodard: Oh, it went so well. At first, I was doing interviews by myself, and you hit this thing where the person knew you and knew you knew the history, and they would say, “You know, right?” But with the kids they wouldn’t do that because they knew they didn’t know. So I started getting all this history that was really breaking the old paradigm that I had learned. And [Amiri] Baraka, in his interview, I asked him about Howard University, and he started to tell me the same story about how corny Howard University was, and Vanessa Whitehead, who was fourteen at the time, she said, “Really? I wanted to go to Howard University.” And Baraka breaks down and says, “Oh you’re right, those were the best years of my life.” [Laughs] And so I started realizing that having those kids there was really a nice, interesting filter. People would lie to me, but they had a hard time telling that same old story to the kids.

Burgin: Right, so do you arrive at graduate school at Penn with these interviews?

Woodard: Yeah, I had a box of fifty or sixty tapes. I wanted to do the project I was working on. And actually, the way it was framed at that time—and there’s no such thing as Black Power studies, right?—is that I was going to rethink the Civil Rights movement. And here’s the weird thing: when I first went to graduate school, I went to study the horn of Africa, but there were so few people in the department that I couldn’t study African history—so as a fallback I took Michael Katz’s urban crisis seminar. And I realize, “Whoa wait a minute now, this makes more sense for me because I was in the housing movement, the tenant movement, and now this is [an academic] subject. When I get out of school, I actually can become an expert in this area because I’ve got this under my belt, so I can match my political experience with the academy.”

Burgin: Did you face backlash against your research project?

Woodard: Well, one person in the department said it wasn’t history! And I knew from people dying around me that obviously it’s history, but also it was history that if we didn’t start interviewing people soon it’s going to be gone … Also when I was getting ready to write A Nation Within a Nation, I was rethinking the dichotomy of the noble poor of the South and the “riffraff” Northern activists. I was trying to include as much detail of how people [in the North] organized themselves. And John Dittmer’s book, Local People, helped me make it at UPenn. Matter of fact, Princeton rejected my manuscript in the beginning with the question, “Who are these people?”… In the academy, you have to have some justification for why you’re studying local people in Newark. “You’ve interviewed fifty or sixty people but so, what? Why are they important?” And so Local People was my first leg to stand on [to say these people matter].

Burgin: How else did you muster forth when there were obstacles?

Woodard: I was in the movement so I was rescued repeatedly—I didn’t make it as an individual. From the beginning, it was a community project. The community asked me to do it, the children joined. Publishing and the university are combat zones where many bodies are buried. Mary [Frances Berry], Evelyn [Brooks Higginbotham] and Michael [Katz] cleared away most obstacles, and then movement folks intervened in the publishing.

Burgin: So as you turned the dissertation into a book, what major revisions did you make?

Woodard: I was teaching at Sarah Lawrence, and the students took over a building, and the dean … recruited me to be a professor. It turned out that those students were the children of SNCC and the Panthers, including Joju Cleaver who [is] Kathleen Cleaver’s daughter. And they had these questions about their parents because they couldn’t find their parents’ history in any of the books. So first of all, I restructured it to aim at the children of the Black Power/Civil Rights generation who were sitting in front of me because they were literally reading my dissertation chapters, and I answered their questions … And then [an earlier trip to] Mississippi affected me profoundly. People were being interviewed [about the movement], and I had a notebook and was writing all this stuff down. And everything we heard was totally the opposite of the narrative in the books about the Mississippi movement. What happened was the guy who collected the money for the voting rights campaign [in one location] sounded to me like what we knew in Newark as a numbers-runner. The woman who put SNCC up in her place [in one location] ran an illegal liquor operation there. So it became very clear to me that this “riffraff” theory they had of the Black Power movement [and the North], versus the angels in the Civil Rights movement story, was misplaced … The other thing was that the women in Mississippi [including Unita Blackwell] took me in as soon as I got there [on that trip]. So over and over again, it reminded me of the meetings I was in in Newark [as an activist], where the first couple of meetings I went to in Newark [were] all women and me—like forty women all crowded into a public housing [living] room … I kept looking at the way they were teaching the absence of women’s leadership, and I kept saying “Well gee whiz, maybe I’m wrong but I was in a different part of the movement because I was surrounded with women leaders.”

Burgin: So then, when the book came out, did you get any criticism from people about your involvement with the movement you were writing about?

Woodard: No. Actually, I hid that to that extent, and the first version of it, I don’t say I’m there. And Michael Katz, I think, was the one who said, “You need to reveal that fact.” But … I thought people were demoting memoirs and not making it part of the scholarship … So I decided the best way to intervene and change the narrative was to write it as if I wasn’t there. And matter of fact, there are scenes in the book where I’m there, but I talk about the three other people who were there rather than me. At the Gary convention in 1972, I was Amiri Baraka’s secretary; I took the notes in each state caucus. Thus, I’m always disappointed when scholars insist that Black Power was a thoughtless movement—even in the face of the Gary Agenda.

Burgin: Looking back on the book now, it’s been twenty years, is there anything that you wish you would have paid more attention to in the book?

Woodard: Oh, massive things. I definitely think that that earlier convention movement in the 1950s [was important, and] now I know the National Negro Congress was so important. I would also hit the Jim Crow North a lot more succinctly. The North is probably the cutting edge of how you do Jim Crow, and by having the South as the model, we have a dull cutting-edge.

Burgin: And what are the things that, looking back on it, are real marks of pride for you around the book?

Woodard: Well, just the appreciation that people had that I had gotten the story right. That’s the big thing is—you’re writing the story, you’re in isolation, and you’re hoping that you’re getting as many of the voices in there as possible, right? And for people who were in the movement to tell me that I got the story right, that was my big award. Because you’ve got the empire that’s writing these dissertations, and then all the dissertations are going to the university library so that the big universities can read those and exploit those communities, right? But the most important thing is to take it back to the children whose parents made that history, and say, “This is who your mother was. This is who your grandmother was.” And I got it from the kids. When we went to the senior citizens project to interview those old people who had been in the movements, Vanessa Whitehead is walking to her public housing project with me—because I have to take the kids home after an interview—and we’re walking through the litter and the garbage in the streets of Newark. But her head is suddenly held up high, and I say, “What are you thinking?” She said, “We have a history.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.