Locating Black Queer Pasts

Black queer histories—those that index the forms of social life that have flourished in the shadows created by state-sponsored violence, neglect, and marginality—are a roadmap to an alternative horizon, one in which our love, our eroticism, might be mobilized to rethink the very contours of reciprocity, intimacy, belonging, and collectivity. The recovery of these usable histories is not a straightforward endeavor, however, because the names ascribed to discredit the practice of communion in spaces of death proliferate: “matriarchal families,” “cults,” “gangs,” “addicts,” “faggots,” “bull-daggers.”

These names invoke dangerousness and the novel formulations that have happened under them remain unintelligible except as life not worth the living; as that which must be excised or sanitized to preserve the rest; as that which is the locus and origin of disproportionate death. In order to recover black queer histories—the generative practices of social life where life is not supposed to be more than simply the history of black people engaged in same gender sex—requires the critical rearrangement of the events, details, memories, and facts we inherit about the past.

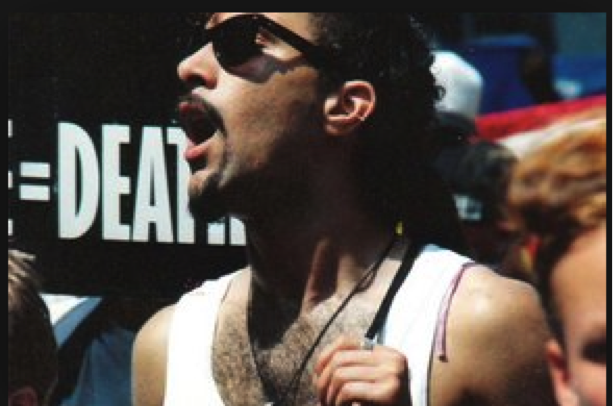

Jon Paul Hammond was the architect of a future we have yet to fully realize in which affiliation, mutuality, reciprocity, communion, and kinship might finally displace dominance, hierarchy, incommensurateness, and brutality. Hammond envisioned a world in which robust forms of social responsibility would dissipate the social borders enacted in the landscape through policy and enforced with violence. He, like so many other black queers, was not defined exclusively by sexual orientation, but rather through an orthogonal relationship with compulsory forms of normativity in community. He was queer in relation to his sexuality but also in the sense that he was strange, odd, and often unsettling.

Born to interracial parents in 1960 in a segment of North Philadelphia that the city and investors abandoned except through policing, by college Hammond embraced sartorial choices that marked him as gender non-conforming. He did not fit comfortably within a single political identity or practice. Although the shaming of his person around this non-normativity inspired a deep melancholia, it was also the source of alternative power upon which he drew in reimagining community to include the city’s most marginal. As a black queer anarchist who embraced the Quaker tradition of peace activism and as an active participant in Philadelphia’s Arch Street Friends Meeting House, Hammond helped to instigate new forms of human connection, community, and reciprocity up and out from the realm of the intimate that included HIV positive people and drug users.

Hammond envisioned and practiced reciprocity with people that the city and black political figures considered refuse and this led him to his life’s work as a harm-reductionist. He was one of the co-founders of Philadelphia’s front-line HIV-AIDS and harm-reduction organization, Prevention Point between 1991 and 1992 that began as a guerilla needle exchange operation initially unsanctioned by the city and illegal in the state of Pennsylvania. Even after his time with Prevention Point, Hammond helped to press the national Harm Reduction Coalition beyond its comfortable academic posturing to deal with and address the capacity for drug users and HIV positive people to serve as their own representatives and to be full members of wider networks of community. For Hammond, the imperative to include these marginal actors was part of a vision of challenging the radical social and geographic borders that created the conditions for disproportionate premature death in the first place. He saw including the most marginal as a way toward peace within the setting of small-scale community, but also in the wider world.

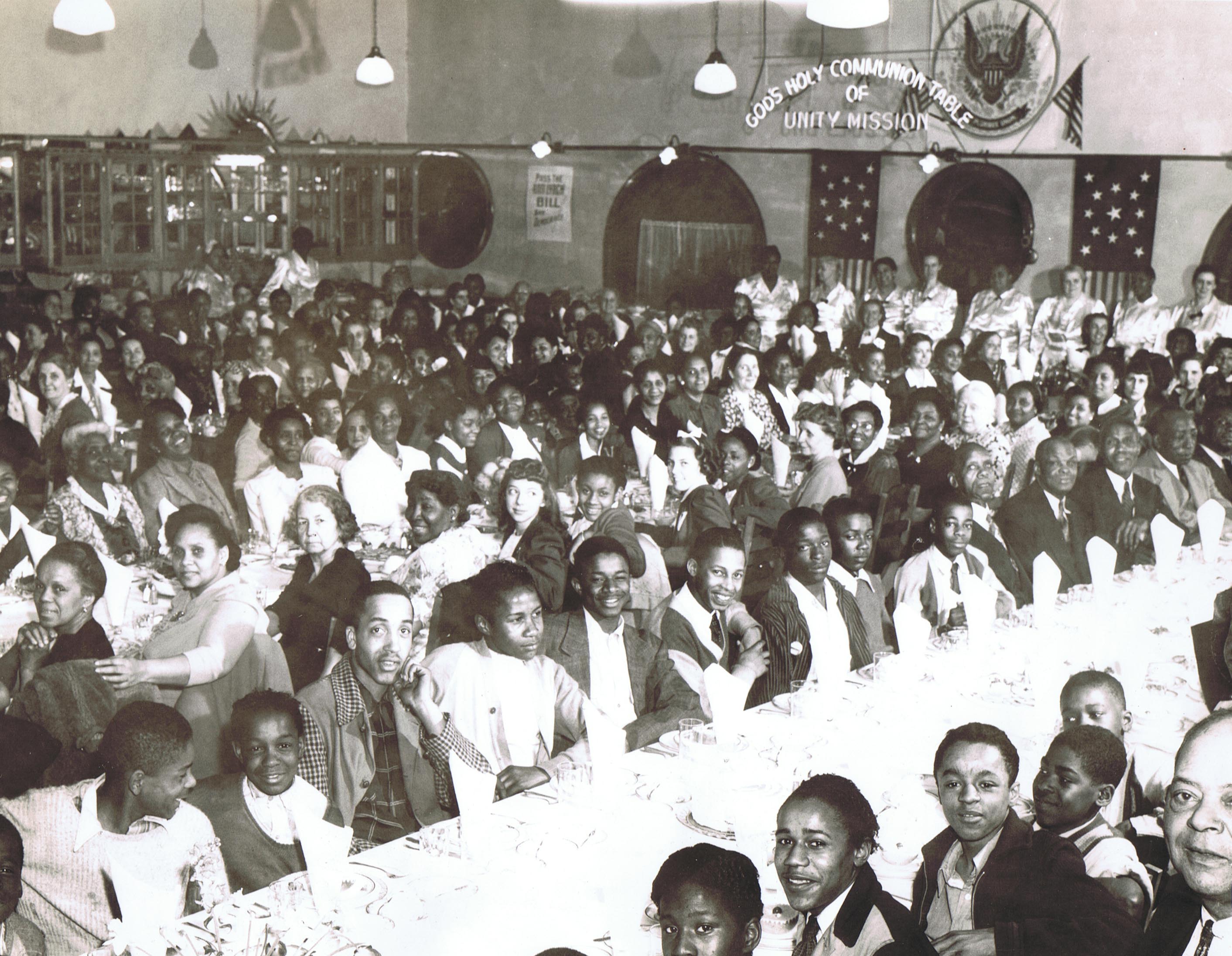

In this vision, Hammond built on the dreams of black subterranean institutions—those invisible or disavowed by reformers and the state alike—even before his birth. In his life-work to bring drug users into the fold of Philadelphia’s community as a constituency in their own right, Hammond built specifically on the earlier efforts of Father Divine’s International Peace Mission Movement—a group often dismissed from our accounts of black political histories because of its oddity and its esoteric doctrines, because “cults” are more comfortable if they remain in the dustbins of the past.

Despite our inherited sensibility that cults are simply composed of charismatic leaders followed usually by mostly women dupes, the adherents of the Peace Mission began practicing a world where the social borders of race and class might be diminished in order to interrupt war. Shifting center in the early 1940’s from Harlem to Philadelphia, the Peace Mission continued to disrupt the social conventions that upheld segregation as a tenet of order and peace. Hammond’s grandmother, father, aunts, and non-blood kin were all adherents of the Peace Mission at one point or another, and although his father Bunch Hammond and some of his other family members had absconded the Mission, they carried forward its radical challenges to social hierarchy and its primary imperative, peace. Thus, Hammond’s embrace of a notion of peace and a non-hierarchical world in which social affiliation might be imagined from within the spaces of the most marginal, built on the practices forged by adherents of the Peace Mission of spiritually appropriating segments of the urban landscape to practice a different kind of world.

As the nation’s social orphans, as people for whom the powerful on one continent disavowed connection and sold to the powerful of another continent, black communities of the Diaspora have derived their alternative structures of power from the ability to forge connection across differences. This process began in the hull of the ship, then across the boundaries of blood kin on plantations, and more recently in the pressure cooker of confining ghettos. The queerness that undergirds black vitality—that ability to practice communion from within the spaces of death, the instigation of life where it is not supposed to be—is among our chief resources. But we do have to part with the kinds of tame research and writing we are disciplined into in order to locate these pasts. Our future depends on it.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for introducing me to Jon Paul Hammond’s incredible story! Beautifully and powerfully written.

Thank you for your engagement!

Thank you for locating and making visible this important strand of African American history.

Thank you for reading !

Powerful story! Especially, “The queerness that undergirds black vitality—that ability to practice communion from within the spaces of death, the instigation of life where it is not supposed to be—is among our chief resources.” Thank you for sharing Jon Paul Hammond’s story with us.

I appreciate you!

Thankyou

I appreciate the read.

Beautifully written.

“As the nation’s social orphans, as people for whom the powerful on one continent disavowed connection and sold to the powerful of another continent, black communities of the Diaspora have derived their alternative structures of power from the ability to forge connection across differences.

Thank you for introducing me to Jon Paul Hammond.

Thank you!

Jon Paul was a friend and comrade of mine in ACT UP Philadelphia and Prevention Point Philadelphia. He was a challenging person who pushed us to reconsider our definitions of what needed to be done, what was possible and what was most urgently needed. I was very fortunate to know him. Thank you particularly for connecting this talent of his to his knowledge of the Peace Mission Movement. I hadn’t thought of that. We Quakers are very much about “spiritually appropriating” parts of our existing surroundings “to practice a different kind of world”. Jon Paul’s vivid ability to do that — making an abandoned, dangerous lot into a place of healing and hope by mobilizing harm reduction — was exactly that. I never considered that he was reinterpreting the principles of the Peace Movement he observed, as well as so many others. Thanks very much for this piece.

Thanks for these reflections! I would love to talk more about this with you if you are willing.

Thank you so much for this. John Paul was also a kind and gentle soul. He was a major part of Prevention Point Philadelphia and demanded sterile syringes in order not to contract hepatitis c and HIV. He organized many actions for ACT UP Philadelphia.

Thanks for sharing your memory of JP!