Leveraging the Law

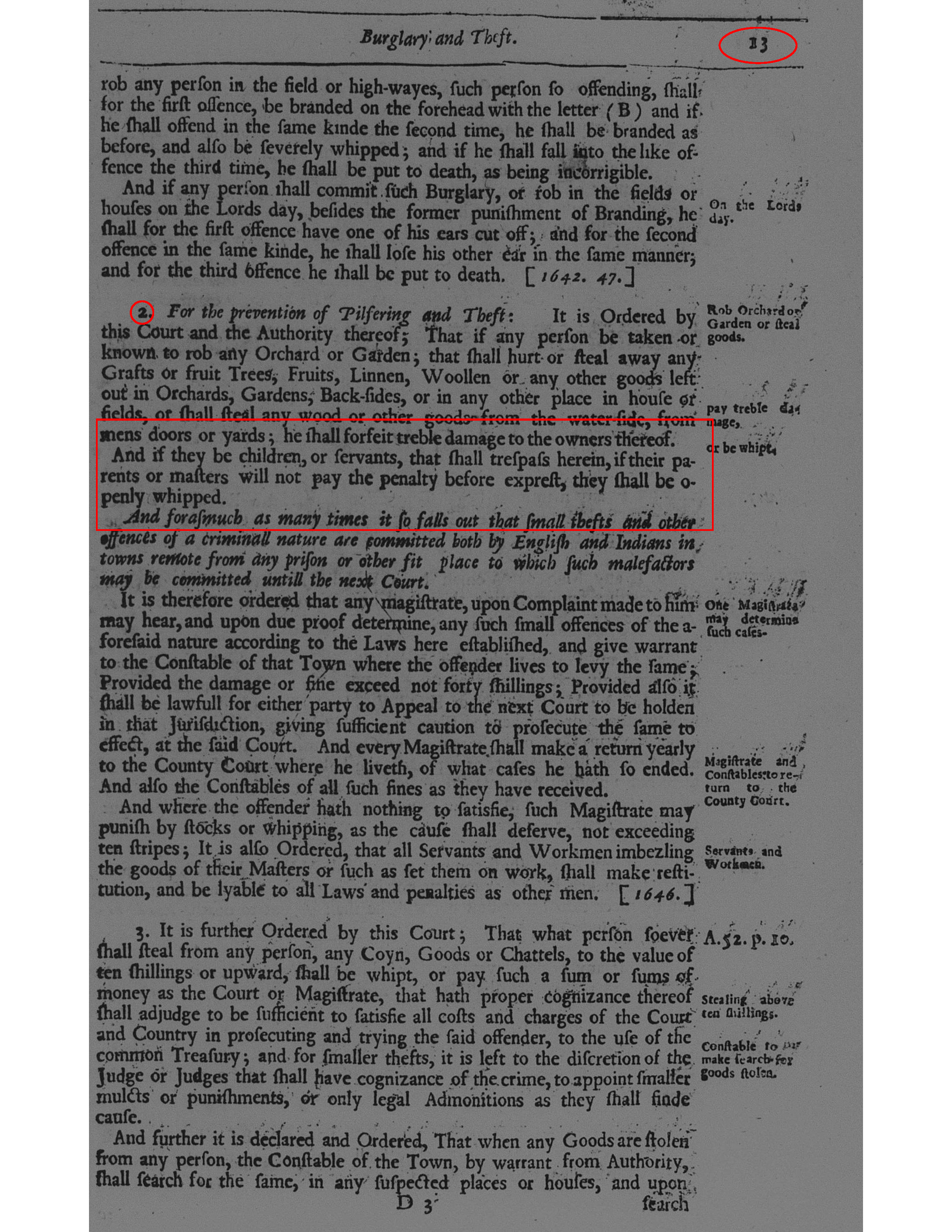

In the 1670s, an enslaved woman named Hannah appeared before Boston’s criminal court accused of stealing surgical equipment from Daniel Stone and selling it to Mary Pittum. When found guilty, fined, and sentenced to be whipped, Hannah appealed her decision. Between her sentence and appeal, she received the lashes, but at her next appearance in court, Hannah protested the fine. According to the enslaved woman, “Law titell buglery theft page :13 section 2,” prevented servants and children found guilty of crimes from being fined and they could only be “openly,” or corporally, punished. Although the court rejected Hannah’s appeal, her protest demonstrates enslaved men and women could have a deep and profound knowledge of Euro-American law.

Over the past three months, I have written on slave literacy, early black intellectual networks, and finding slave initiative and agency in unexpected places. Today, I want to triangulate those three themes, peering into early American courtrooms to understand how enslaved and free black men and women sought meaning in and knowledge of the law. The use and understanding of legal mechanisms allowed early African Americans to better navigate, decode, and confront an alien and hostile world. It also helps us to better understand how blacks envisioned themselves intellectually within the legal system. Once again, I will be using early New England as an example.

Let’s return to Hannah. To better understand her case, we need to find out which law Hannah referenced. While colonial officials first passed the law regarding servants and children in 1648, Hannah mentioned a specific page number in her appeal. Her reference—page 13—can be found in the 1672 edition of The General Lawes and Libertyes, the legal code governing the Massachusetts Bay Colony. That page, section two, also noted by Hannah, contained a clause regarding servants and children, noting that if the master or parent did not pay any fine levied, the dependent was to be physically punished. Under Hannah’s interpretation of the law, her master did not pay the fine and she had been whipped, which should have marked the end of her punishment.

The bigger question remains how Hannah had such intimate and specific knowledge of the law. There are a few possibilities. First, although she signed the document with an “X,” it is quite possible that Hannah could read. In Puritan Massachusetts, many women learned to read, but often were not able to write. Given the proliferation of these law codes—the colony printed hundreds of copies of each—she could have easily had access to a copy of the 1672 edition. Likewise, her master, a fellow slave, or even her co-conspirator Mary Pittum could have coached Hannah. Moreover, legal knowledge in the early modern Anglophone world was largely decentralized. While there were certainly lawyers and attorneys around the English Atlantic, everyday juridical process—including the prosecution of petty crimes like Hannah’s—was not often in the hands of professionals. Usually leading community members, these amateur jurists had access to a proliferation of books and manuals for how to administer the law. With so many instruction manuals and law codes floating around and with such a literate population, legal knowledge was radically democratized and accessible, allowing even marginalized members of the community like Hannah access to the law through reading or coaching.

Yet, we have to read deeper into Hannah’s appeal. Although it ultimately failed, Hannah’s legal acumen suggests a deeper understanding of the law and her place within Euro-American society. Hannah was a slave, yet she appealed using a law that governed the behavior and actions of servants and other dependents. Certainly, given her demonstrated knowledge, Hannah would have realized she, as a slave, was legally distinct from a servant. Indeed, it is probably why she lost her appeal. Why, then, did Hannah attempt to appeal to servant law?

To answer that question, we first need to explore the career of John Clark, a justice of the peace in Boston from 1700 to 1726. In his casebook, we see slaves regularly approaching Clark to address their grievances. Clark often helped enslaved Bostonians seek redress and would even punish those who abused enslaved men and women. One case involved John Peak, a Boston sawyer. Clark forced Peak to post a 40-pound bond and to appear at the next session of Boston’s criminal court to explain the “cruel treatment towards his Negroman Primus.” Primus, the abused slave, initiated this process by asking the justice to protect him from his master.

On the surface, the cases of Primus and Hannah have little to do with one another. In reality, however, they are two sides of the same coin. Much like Hannah, Primus appropriated servant law to find protection from his master. In the English legal system, servants had the right to appeal to a justice of the peace if their master was abusing them. Unlike Hannah, however, Primus won. Clark, by forcing Peak to appear in court to explain his mistreatment of Primus, acknowledged that he was—at least in this instance—a servant and legally recognized as such.

Enslaved men and women probably learned about servitude much like they learned other facets of the law. Every book printed for use by jurists had a section on servitude, which enumerated the rights, duties, and obligations of servants in a clear list. Likewise, in the eighteenth-century American colonies, slaves were surrounded by unfree whites—indentured servants, convicts, and apprentices. It was not uncommon for bound blacks and whites to live in the same household and socialize. Through something as fundamental as association or friendship, slaves could have learned about the law of servitude and its relative—compared to slavery at least—fairness.

Historians of slavery in New England have often been confounded by the constant reference to African slaves as “servants,” throughout out the colonial period. I contend it was at least partially at the insistence of enslaved people like Primus and Hannah to be recognized as servants and they played an active role in the creation of this classification system.

Using knowledge of the law, slaves in New England sought to be legally identified as servants. This behavior can be interpreted as a fight against degradation and racialization. Slaves, legally speaking, were the property of his or her master, subject to their owner’s whims and abuses, and in the law only identifiable as an extension of their master’s will. Servants, on the other hand, had rights, judicial recourse, and legal personhood. Fighting to be identified as servants gave enslaved people claims to rights and privileges and a place in the social order. Of course, this was certainly an imperfect arrangement, slaveholders challenged slaves’ assertion of agency, and the state continued to use racialized means of control. Nevertheless, there was something of a compromise reached by the mid-eighteenth century where slaves were often legally classified as “servants for life.”

In the end, the ability of enslaved New Englanders to navigate the difference between slavery and servitude informs a larger conversation on the way slavery functioned and the role of slave agency within it. It suggests slavery was more of a dialogue between masters and slaves and while brutality and violence were omnipresent, slaves could use knowledge of Euro-American society to make their own appeals and protests to mitigate some of the worst aspects of slavery. Although imperfect, the ability to use the law transformed slavery from a totalizing force of oppression to a structure that could be reshaped and challenged from those living under its strictures. Through continued legal activism, women and men like Hannah and Primus exposed the contradictions, logical flaws, and inconsistences within the system of slavery, helping to forge paths to freedom and emancipation for future generations.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Bravo to these brave and courageous women and men who stood up and questioned authority!

In 1771, Prince Hall helped his wife, Flora Gibbs, sue a prominent landowner from a slave-owning family for damages and interest. Apparently, Francis Norwood had not paid his Gloucester-born wife for services dating from 1769. Hall advised the Essex sheriff where to look for Norwood in Gloucester in order to help recoup their £10. The Norwood name survives to denote Gloucester neighborhoods and streets.