Josephine Butler and Environmental Activism in Washington, DC

The first time I heard about Josephine Butler was when I stepped into the building named after her––the Josephine Butler Parks Center. Located at 2437 Fifteenth Street NW in Washington, DC, adjacent to the Malcolm X Park (also known as Meridian Hill Park), the Josephine Butler Parks Center––referred to as the “Embassy of the Earth”––was once the former embassies of Hungary and Brazil. Operated by Washington Parks and People, a non-profit whose mission is to “grow city-wide park[s] based on community health and vitality by nurturing innovation and partnerships,” the Center is located on sacred grounds––as the Malcolm X/Meridian Hill Park and adjacent area were once the loci for “Native American spiritual territory; the birthplace of both George Washington University, and an African-American theological seminary; and a Civil War Union Army hospital.”

While the Center itself is enchanting––its light-yellow exterior and interior serve as a popular wedding venue in Washington, DC––it is the resounding activism of Josephine Butler, a Black woman who catalyzed change in Washington, DC––that made me want to know more about her. I also began to wonder why I did not know about her or her political contributions prior to entering the Center.

Josephine Dorothy Butler––who was affectionately known as “Jo”––was born on January 24, 1920, in Brandywine, Maryland. Her parents were sharecroppers and her grandparents were enslaved peoples, whose hometown and origins are unknown. After attending Frederick Douglass High School in Upper Marlboro, Maryland and Strayer College, and suffering from typhoid, Butler moved from Brandywine to Washington, DC in 1934 to receive better medical treatment. She would remain in DC and became a champion of racial and gender equity and a prominent community leader.

Butler “started America’s first-ever union of Black women laundry workers.” She gave Black women domestic workers confidence in demanding and asserting their rights and agency in and out of the workplace. After the passing of the 1954 landmark Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, Butler was pivotal in the peaceful desegregation of Thomas P. Morgan Elementary School, a predominantly Black school, and John Quincy Adams Elementary School, an all-white school, in 1955. It is because of her bravery and activism that the “neighborhood of Adams Morgan, a combination of the schools’ names, now stands as a reminder to honor racial and cultural differences.”

In the latter part of the 1950s and during the 1960s, Butler’s advocacy would activate change in metro DC. As a leader in environmental activism, she served as a community health educator for the American Lung Association in DC, where she educated thousands of children about air pollution before the movement for environmental justice and climate change existed. After becoming disillusioned with the Democratic Party because of the egregious police brutality at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968, she left the party.

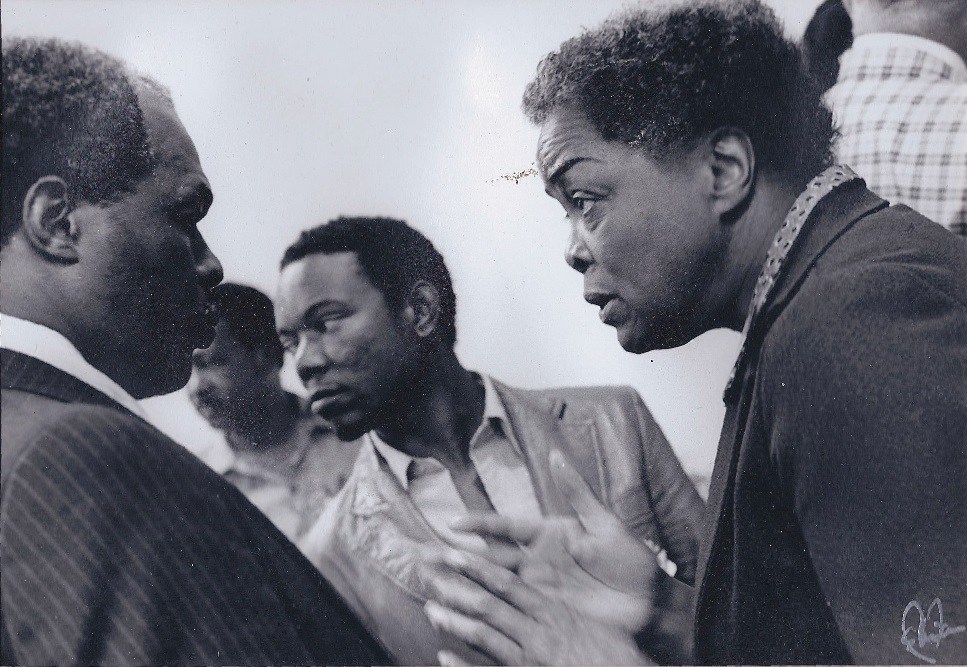

In 1971 Butler co-founded the DC Statehood Party Committee with Julius Hobson, the former president of the Congress of Racial Equality, to “redress the inequity that Washington residents were not able to exercise their full rights as citizens because they live in a federal district controlled by the U.S. Congress that does not have voting representation in Congress.” In 1977 she was named chair of the Statehood Party and would run twice for DC Council on the party’s ticket. Having affiliations with the Communist Party USA and supporting other Marxist organizations, demonstrations, and collaborators, she was also the founder of the World Council of Peace (WCP), an international, anti-imperialist organization that promotes peace, universal disarmament, social justice, human and environmental rights, national independence, and sovereignty. She organized WCP’s first meeting in the US. As a representative of WCP, she visited the Soviet Union, Greece, and Grenada in efforts to promote global peace.

With her passion for revitalizing parks and recreation, reforming healthcare, and creating safe community havens for children and families, she would continue to be “involved in almost every critical political movement” that occurred in metro Washington, DC. Butler founded the DC chapter of the Paul Robeson Friendship Association and was the co-chairperson of the Friends of Meridian Hill Association. In conjunction with these associations, she and other community leaders and activists transformed Malcolm X Park, which was once known as the city’s most dangerous park, into a communal, artistic, and educational refuge. In 1994 Butler introduced President Bill Clinton during an Earth Day speech at Malcolm X Park. That same year because of her work in mobilizing nighttime neighborhood watches to counter violence, planting trees to prettify the park, and organizing community-wide events, she was awarded the National Partnership Leadership Award from President Clinton during a White House ceremony.

Serving as the former representative of the Mayor’s Health Planning Advisory Committee, the DC Human Rights Commission, and the DC Coordinating Committee for the International Women’s Year, in 1995 she “organized a parade of 4,000 people from her Adams-Morgan neighborhood to the Capitol, where she addressed a crowd estimated at 250,000 people who had gathered to mark the 25th anniversary of Earth Day.”

After dedicating most of her life to social justice, racial equality, and community engagement, Butler died on March 29, 1997, at the age of seventy-seven. While reflecting on Butler’s activism, I found myself wanting to read more literature about this woman who revolutionized DC and the rest of the nation. However, like countless Black women activists, matriarchs, and heroines in the African Diaspora, there is little scholarship about the life and legacy of Josephine Dorothy Butler. Butler’s desire for justice and political reform birthed her community involvement, and her contributions should be forever etched in history. Here her life is not only a call-to-action for me to continue in my intellectual and political activism, but also to ensure that the lives of Black women activists, like Butler, do not go unseen, unheard, and unrecognized in the history of Washington, DC.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.