On John Pory, America’s First Racist

Have you ever heard the name John Pory?

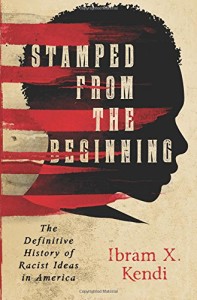

It is a name all students of American history should know. It is a name all students of America’s racial history should certainly know. It is a name I did not know when I embarked on my research journey for my new book, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America.

John Pory can be identified as America’s first known racist. Known is the decisive word. Based on the available evidence, Pory appears to have been America’s first known articulator of racist ideas in a murky and complex history that can be traced back to those early years of the colonial era. As I narrate in #Stamped, the history of racist ideas spans the full course of African American history, from the origins of colonial America to the present. Racist ideas preceded the American Revolution because the need to justify African slavery preceded the American Revolution. Racist ideas even preceded colonial American slavery because the need to justify slavery preceded the British settlements in America.

The origins of America’s racist ideas–like the origins of the earliest American settlers–cannot be found on American soil. The origins of America’s racist ideas can be found in England and throughout the broader Atlantic world.

Around the time Johh Pory was born in England in 1572, the greatest British promoter of the colonization of North America began voraciously collecting and reading all the overseas travel stories he could find. By the time the studious Pory enrolled in Cambridge, Richard Hakluyt had published an anthology from his mammoth collection of travel stories. In his monumental Principall Navigations, Voyages, and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589), Hakluyt urged Englishmen like Pory to fulfill their superior destiny, to overtake the other Western European superpowers, in order to civilize, Christianize, capitalize on, and command the non-European world.

Not much of a traveler, Hakluyt surrounded himself with a legion of travel writers, translators, explorers, traders, and investors—everyone who might play a role in colonizing the world. Hakluyt mentored Captain John Smith, who steered the expedition of those three British boats that entered Chesapeake Bay in 1607 and founded the first permanent English settlement in North America.

After returning a hero to England in 1609, Captain Smith became Hakluyt’s greatest literary mentee. Thousands crossed the Atlantic Ocean because they were moved by Smith’s exhilarating travel books, which by 1624 included his tale of Pocahontas saving his life and by 1631 referred to African people “as idle and as devilish [a] people as any in the world.” But Smith was only reproducing the racist ideas he had heard in England—some of which can be traced back to the pen of John Pory—another eminent mentee of Richard Hakluyt.

In 1597, Hakluyt urged Pory to complete a translation that may have been on Hakluyt’s translation list for quite some time. Obliging, Pory began translating into English, A Geographical Historie of Africa, by Leo Africanus.

It was first known survey of Africa in Europe. A Geographical Historie of Africa was based on the observations of a well-educated African Moor. Leo Africanus claimed to have traveled below the Sahara Desert before he was enslaved on the Mediterranean Sea and presented to the learned Pope Leo X in Italy. Before dying in 1521, the Pope freed the youngster, converted him to Christianity, renamed him Leo, and probably commissioned him to write this book. Leo, who took on the name Africanus, obeyed and satisfied the curiosity of Italian readers.

The Africans “leade a beastly kind of life, being utterly destitute of the use of reason, of dexterities of wit, and of all arts,” Africanus summed up in 1526. “They…behave themselves, as if they had continually lived in a Forest among wild beasts.”

Leo Africanus may have never visited the fifteen African nations he claimed to have seen. He could have paraphrased the work of Portuguese intellectuals—those originators of racist ideas who rationalized Portugal’s pioneering slave trading of African people during the long 15th century. But veracity did not matter. Once Africanus’s manuscript was published in Italian in 1550, once it was translated into French and Latin in 1556, once John Pory published his English translation in 1600, readers across Western Europe were consuming it and tying African people to hyper-sexuality, to animals, and to lacking reason. Pory brought to English readers the most popular, the most racist text on Africa during that critical 16th century when France, Holland, and England began their African slave trading.

When Pory published his translation of Africanus’s text in 1600, the first major debate had already been raging between racists, or between curse theorists and climate theorists, or between nature and nurture as explanations of inferior Blackness. Curse theorists explained their racist ideas of natural Black inferiority by evoking God’s curse of Ham in Genesis, by claiming African people were the cursed descendants of Noah’s son, and by stressing that African people were permanently inferior. Climate theorists explained their racist ideas of nurtured Black inferiority by evoking Africa’s hot sun, by claiming the beaming sun had darkened Black skins and minds, and by stressing that African people could become White and equal again if they moved north and assimilated into a cooler climate.

In his long introduction, Pory argued climate theory could not explain the radical distinctions in skin color. They must be “hereditary,” Pory suggested. “Negroes and blacke Moores” are “descended from Ham the cursed son of Noah.”

Pory’s translation of Africanus’s racist tract in 1600 immediately impacted racist thought during those intervening years before the settlement of Virginia in 1607. William Shakespeare used and capitalized on the popularity of Pory’s translation in his plays, particularly in The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice, which premiered in 1604. Shakespeare’s “lusty More” obviously resembled Leo Africanus, that Christian Moor of Italy who despised his Blackness. Shakespeare’s rival playwright, Ben Jonson, used Pory’s translation to produce The Masque of Blackness, the grand coronation of King James I in 1605.

As his book and its racist ideas spread, Pory accumulated relationships with a host of influential Englishmen. He served in Parliament from 1605 to 1610, and then traveled abroad for five years serving as a secretary for English ambassadors. He almost certainly followed the growing popularity of the curse of Ham theory among British intellectuals in the early 17th century, as showcased in the writings of poet John Taylor, Rev. Thomas Cooper, politician Thomas Peyton, and Samuel Purchas, another mentee of Richard Hakluyt. (Pory and his British peers had no idea that this curse theory would become the most popular racist theory in the long justifying history of American slavery).

In the summer of 1619, Pory ventured to Jamestown to serve as the secretary for his cousin, the colony’s wealthy governor, George Yeardley. On July 30, 1619, Yeardley convened the inaugural formal meeting of politicians in colonial America, a Virginia Assembly that included Thomas Jefferson’s great-grandfather. These lawmakers named John Pory the first Speaker of the Virginia Assembly. The English translator of Leo Africanus’s thoroughly racist book—the first known influential Englishman on America soil with a record of articulating racist ideas—became colonial America’s first legislative leader.

John Pory set the price of America’s first cash crop, tobacco, and recognized the need for more labor to grow more of it. So when the first known slave ship carrying African people arrived on the shores of Jamestown weeks later in August 1619, those 20 enslaved Angolans were right on time. And the racist ideas John Pory had just brought over from England were right on time to justify their enslavement.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Very well written and an informative piece. It appears that whites from that period of time were very easily influenced by those more travelled, hence the overall process of the brainwashed mind still present in most white people today. At 43, I am finally getting the chance to gain understanding about true history as it relates to me as a black person. Thank you, Dr. Kendi.

The beginning was not in Jamestown, but at Point Comfort – Elizabeth City County, (present day Hampton), VA, where Angolans (Africans) disembarked the White Lion. Some stayed in Elizabeth City County, and some Angolans (Africans) were taken to Jamestown.

The problem with saying anyone was the first racist is that it ascribes sole authorship to what was a deeply rooted mass ideology with many tendrils reaching into many historical experiences and ideologies. Also, it was a racist tract, not a racist track.

Unfortunatly racism is increasing instead of decreasing. This is sad but true.

My understanding is that the first Africans arrived as indentured servants and were freed when their period of indenture ended. This practice lasted for into the early 18th century when Africans became chattel slaves.

Ι read it with pleasur. Really interesting article!!

After reading your articles i became very keen follower you..

I always prefer to read the quality content and this thing I found in you post. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for writing such a wonderful article, it is really going to motivate people to achieve something big and dream bigger in future.