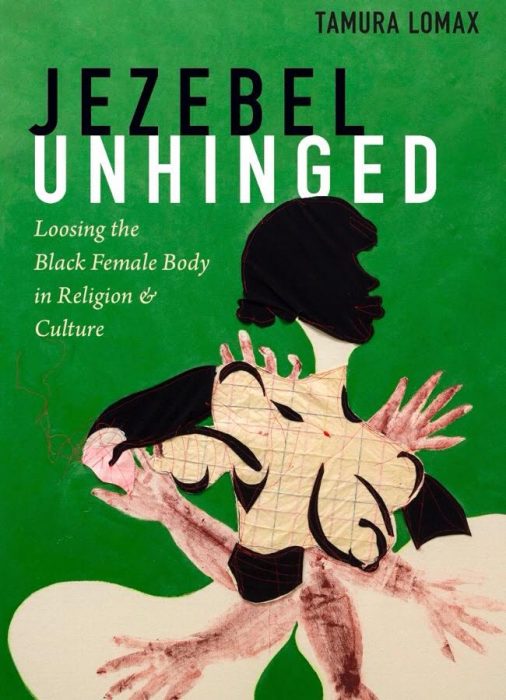

‘Jezebel Unhinged’: A New Book on the Black Female Body in Religion and Culture

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. Jezebel Unhinged: Loosing the Black Female Body in Religion and Culture was recently published by Duke University Press.

***

The author of Jezebel Unhinged is Tamura Lomax, an independent scholar and researcher. She has a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University in Religion, where she specialized in Black Religious History and Black Diaspora Studies and developed expertise in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Black British and U.S. Black Cultural Studies. She is also co-editor, along with Rhon S. Manigault-Bryant and Carol B. Duncan, of Womanist and Black Feminist Responses to Tyler Perry’s Cultural Productions (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). Currently, she is finishing up her latest book, Raising Non-Toxic Sons in White Supremacist America (managed by Don Congdon Associates, Inc.). Recently, she curated the Special Issue entitled “Black Bodies in Ecstasy: Black Women, the Black Church, and the Politics of Pleasure” for Black Theology: An International Journal. Dr. Lomax is also the co-founder, CEO, and visionary of The Feminist Wire (TFW), an online publication committed to feminist, anti-racist, and anti-imperialist socio-political critique. She is also an editor, along with Monica Casper and Darnell Moore, of a book series from the University of Arizona Press: The Feminist Wire Books: Connecting Feminisms, Race, and Social Justice. Follow TFW on Twitter @thefeministwire.

The author of Jezebel Unhinged is Tamura Lomax, an independent scholar and researcher. She has a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University in Religion, where she specialized in Black Religious History and Black Diaspora Studies and developed expertise in Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Black British and U.S. Black Cultural Studies. She is also co-editor, along with Rhon S. Manigault-Bryant and Carol B. Duncan, of Womanist and Black Feminist Responses to Tyler Perry’s Cultural Productions (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). Currently, she is finishing up her latest book, Raising Non-Toxic Sons in White Supremacist America (managed by Don Congdon Associates, Inc.). Recently, she curated the Special Issue entitled “Black Bodies in Ecstasy: Black Women, the Black Church, and the Politics of Pleasure” for Black Theology: An International Journal. Dr. Lomax is also the co-founder, CEO, and visionary of The Feminist Wire (TFW), an online publication committed to feminist, anti-racist, and anti-imperialist socio-political critique. She is also an editor, along with Monica Casper and Darnell Moore, of a book series from the University of Arizona Press: The Feminist Wire Books: Connecting Feminisms, Race, and Social Justice. Follow TFW on Twitter @thefeministwire.

In Jezebel Unhinged, Tamura Lomax traces the use of the jezebel trope in the Black church and in Black popular culture, showing how it is pivotal to reinforcing men’s cultural and institutional power to discipline and define Black girlhood and womanhood. Drawing on writing by medieval thinkers and travelers, Enlightenment theories of race, the commodification of women’s bodies under slavery, and the work of Tyler Perry and Bishop T. D. Jakes, Lomax shows how Black women are written into religious and cultural history as sites of sexual deviation. She identifies a contemporary Black church culture where figures such as Jakes use the jezebel stereotype to suggest a divine approval of the “lady” while condemning girls and women seen as “hos.” The stereotype preserves gender hierarchy, Black patriarchy, and heteronormativity in Black communities, cultures, and institutions. In response, Black women and girls resist, appropriate, and play with the stereotype’s meanings. Healing the Black church, Lomax contends, will require ceaseless refusal of the idea that sin resides in Black women’s bodies, thus disentangling Black women and girls from the jezebel narrative’s oppressive yoke.

‘Jezebel Unhinged’ is an ambitious and provocative work that breaks new conceptual, theoretical, and political ground within Black feminist studies. Creating a theoretical space that might be thought of as Black feminist religious thought, it establishes Tamura Lomax as an important critical voice.” —Mark Anthony Neal, Duke University

J.T. Roane: Did you face any challenges conceiving of researching, writing, revising, publishing, or promoting this book? If so, please share those challenges and how you overcame them.

Tamura Lomax: Jezebel Unhinged was birthed in opposition and resistance. First of all, it’s a massive project, spanning multiple critical and competing discourses, disciplines, and centuries. I actually had to leave academia in order to finish it not only in a timely manner but with the critical density I wanted it to have. The current market model of academia is one of “publish or perish,” which doesn’t really allow for the slow tedious process of research, sitting with, writing, and revising — repeat. The merging of the academic marketplace with the public intellectual and the mass mediation of internet writing where everyone is an expert creates a pressure pot where researchers and writers feel rushed. I didn’t want that for Jezebel Unhinged. Given the span of the project, I wanted to take my time and to go not only wide but deep, but without the politics of academia.

This led to an additional challenge, however. Typically when scholars write books they can depend on institutional funding and the institutional name. The current context often places institutional ties over scholarly expertise. Scholarly works are sometimes given the benefit of a doubt due to where one works, rather than whether or not the work is good. What Jezebel Unhinged reveals is that it’s the scholarship that makes one a scholar–not institutional ties. What this meant for me is I had to fund my own research and I had to work harder at clarifying my arguments, connecting the dots, and not only adding something more to the chorus but constructing an alternative lane. That said, I had to become very clear about who I was as a researcher and writer and the kind of work that the book intended to do.

The latter points to my third challenge. I’m a Black feminist scholar of Black religion. However, I wanted to research not institutional religion, traditions, or theology but Black religiosity, and specifically Black Christianity – as it is produced in popular culture. In this way, the cinema, online media, and other venues become the church or Black religious culture, and the cultural producer, the cleric. I remember sending my manuscript to an editor in 2012 who told me she liked the book but, “this isn’t religion…it’s not how it’s studied or written about.” But that was the point: Jezebel Unhinged looks at religion differently and shows other ways that it might be studied. As a religious historian trained in cultural studies, I wanted to read religion through cultural studies; to explore Black religion as an aspect of Black culture, not as an inherently defined theological or Christo-centric project that sits outside of culture in some sort of celestial realm. This particular gaze was unconventional at the time. Ultimately, I had to find a press that understood cultural studies but was open to critical religious inquiry. In the end, Jezebel Unhinged had to make the study of Black religion plain to cultural studies and vice versa.

The other challenges I faced were largely epistemological, theoretical, and methodological. Jezebel Unhinged engages culture and the ways in which it produces not only religious meanings but racialized and gendered meanings. Namely, it examines what I call the “circulating discourse on Black womanhood” and how it locates Black women and girls as either ladies (virtuous women) or hos (jezebels). In doing this, it investigates and historicizes this unspoken marriage between the sacred and profane, or the respectable and the ratchet, dating back to the medieval period. I wanted to theorize how representations of Black womanhood have been shared and negotiated between religion and culture, and more recently the Black Church and Black popular culture. But, I wanted to do so in a way that hadn’t been done. I was disinterested in neat Black and white binaries and thus opted for what I call “the ugly” (a lovely phrase coined by Jeffrey McCune) – or what Joan Morgan refers to as the gray. That said, I wanted to explore the jezebel trope as both a racist sexist cultural production and projection as well as a powerful self-designation. To do this, I had to not only turn to Black feminism but to create an entirely new discourse and methodology: Black feminist study of religion, which includes Black feminist religious thought, Black feminist religio-cultural criticism, and Black feminist theology.

The challenges here are plenty. As with the inception of Black feminist thought, womanist theology, or hip-hop feminism in intellectual discourse, there are the tasks of construction and definition. But more, there is the reality of shaking up previous ground and critiquing the old guard. The politics of the latter can be dicey. In fact, they can be career ending. But this is the beauty of independence. You can create something new and do it both generously and honestly.