James Pennington’s Fight for African Slave Trade Refugees

In the hot summer of 1860, Americans confronted an urgent refugee crisis. Over 1,400 young and destitute Africans, seized by the navy from illegal slave ships, filled a camp on the sandy beach of Key West, Florida. Their presence forced into public view two issues critically important in our own times: the value of black lives and U.S. policies on vulnerable and displaced people. In response, Rev. James W. C. Pennington, a New York abolitionist and former fugitive slave, argued for compassion, accountability, and inclusion as principles that would serve justice and strengthen the nation.

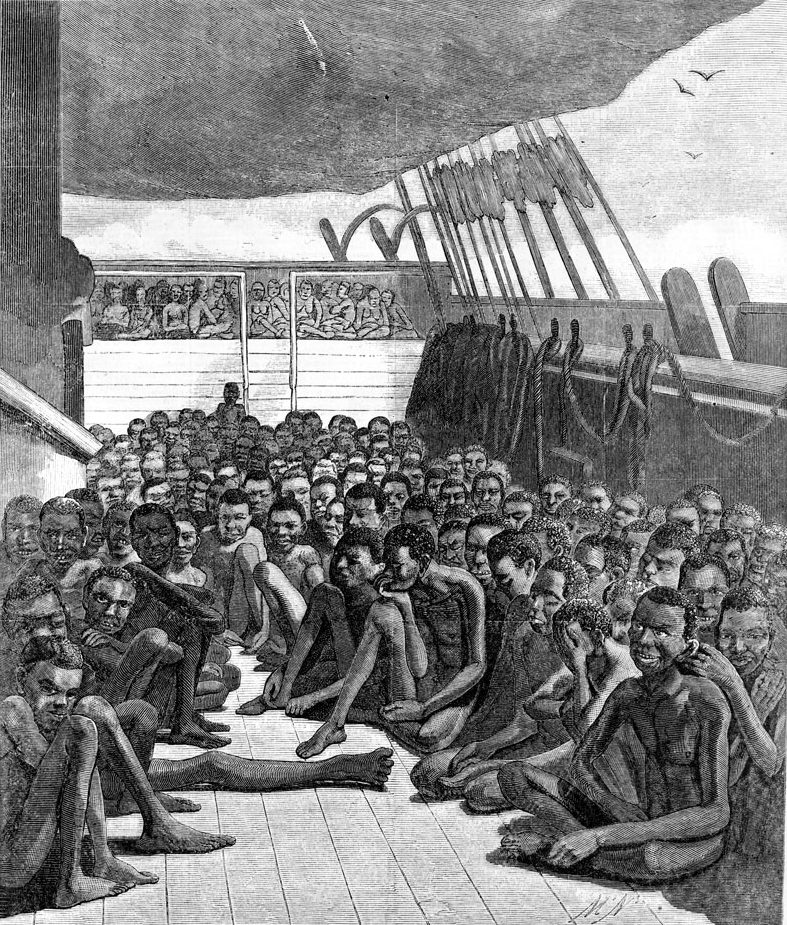

African slave trade refugees differed from today’s asylum seekers in one critical respect: they had never sought to enter the United States but instead had been brutally dislocated through the transatlantic slave trade. Despite a U.S. ban passed in 1807, many American citizens continued for decades to participate in international slaving. Networks of human traffickers forcibly shipped millions of enslaved Africans to Cuba, Brazil, and elsewhere in the Americas. Increasingly large numbers of children and young teenagers (between 40 to 50 percent of all captives in many voyages) were crowded into the holds of illegal slave ships. Naval cruisers who managed to intercept a contraband slaver found hundreds of captives whose youth compounded their vulnerability.

Yet, in many other respects, “recaptured Africans,” as they were called in the United States, shared similar conditions with the 21.3 million refugees and 10 million stateless people counted by the UNHCR today. Recaptives in Key West had been forcibly displaced from their homes. They had traveled thousands of miles across land and sea, experiencing thirst, starvation, and terror. Adults and children alike had been exposed to violent separations and ubiquitous death.

Recaptives who passed into the custody of U.S. federal agents at Key West gained no respite from fear and uncertainty. Southern planters stalked the guarded camp, threatening abduction. Furthermore, recaptives found themselves detained by a slaveholding nation that was fundamentally hostile to free black existence. In fact, a federal statute standing since 1819 called for the removal—or in modern terms, deportation—of any Africans seized from illegal slave ships.

With slave trade refugees dying daily in Key West, federal officials scurried to oversee recaptives’ transportation “beyond the limits of the United States.” It was in this context that James Pennington challenged U.S. recaptive policy. Writing to the New York World in July 1860, Pennington issued a call for compassion. He appealed to the “hearts, humanity, and consistency of the American people” in responding to “these poor young Africans brought into Key West.”

But Pennington did not merely pity recaptives; he saw himself in them. During his childhood in slavery in Maryland, Pennington too had experienced hunger, family separation, and violence. He knew from his own escape to New York at age twenty what it was like to cross dangerous borders. He understood how it felt to be perceived as a threat to white American freedom. Pennington saw the slave trade recaptive issue as one that concerned the value of human life and particularly the value of black life. “If what concerns mankind concerns me, as a man,” he insisted, “surely what concerns my race concerns me.”

To his radical call for compassion, Pennington added a demand for American accountability. He decried U.S. complicity in creating the crisis of recaptive refugees encamped in U.S. ports through weak enforcement of existing slave trade laws. Naval crews who did manage to capture an illegal slaver, he charged, enriched themselves with prize money. Added to this, American courts refused to convict the few slavers put on trial. Here, Pennington’s critique ran counter to the views of prominent naval officers, such as Andrew Hull Foote, who praised naval suppression of the slave trade as a humanitarian expression of U.S. power abroad.

Finally, Pennington supported a policy of inclusion that flew in the face of the removal law. He argued that to shelter recaptives in northern homes would be “more in accordance with our professed humanity and justice” than a precarious deportation of sick and traumatized recaptives. More than an act of charity, the incorporation of African recaptives in households of “farmers, East, West, and North,” offered a potential valuable source of much needed free labor. From today’s perspective, this vision of placing recaptives as apprentices doing domestic and farm labor bears scrutiny. However, at the time, Pennington’s call for care and inclusion contrasted significantly with prevailing support for either enslavement or removal.

Ultimately, James Pennington did not succeed in his call for recognition of the human rights of slave trade refugees. Many more recaptives died on voyages to Liberia, where survivors began a troubled period of apprenticeship. Yet, Pennington’s letters to the World speak to us today by illuminating critical perspectives on U.S. border policies. In the name of justice, James Pennington challenged white Americans to see recaptive Africans for what they were: displaced and traumatized young people caught in the crosshairs of white supremacy and contradictory U.S. laws. He demanded that the nation understand its complicity in producing recaptives’ global displacement. And, he called for alternatives to the politics of rejection that he believed would not only be right, but good for the nation.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Very moving, and important to have this reminder. Thank you, Sharla Fett!

Thank you for your historical piece. It speaks to me in that the more I learn, the more history that needs to be uncovered and presented to the masses.