Integration and Sports in the Age of Trump

On November 8, 2016, 62 million people effectively dismissed Colin Kaepernick when they elected Donald J. Trump as the 45th President of the United States. Consider the gravity of that number. It confirmed black and brown lives and humanity do not matter. At best, it solidified that Blue Lives Matter above all else.

To Trump supporters, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Kaepernick had dishonored the flag and such a disgrace overshadowed healing. On September 1, nearly 2 months prior to an historic day that overwhelmed a nation, Kaepernick knelt during the Star Spangled Banner for a preseason game against the San Diego Chargers. He knelt in love of country. He knelt for the black and brown people, women, gay and trans-communities, and our white brothers and sisters who were tragically slaughtered by law enforcement. Numerous others were inspired by his silent protest and courageously joined in. They too valued humanity.

Their actions were then dismissed on Tuesday, November 8, 2016, when Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. He had swiftly emerged as a political outsider and built his campaign on hate–attacking women, veterans, the LGBTQ community, and those with special needs. He also openly demeaned the existence of Muslims, Asians, Indigenous groups, blacks, and Latinx peoples.

The rise of Trump eerily mimicked the Dixiecrat Party. In the 1948 General Election, Dixiecrats ran on a white supremacist platform that opposed an intrusive federal government and integration. They carried Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina while receiving one additional electoral vote in Tennessee. Trump vindicated the late Strom Thurmond and won the presidency. Many of our white brothers and sisters remained quiet during this new Age of Kaepernick that renewed debates on protest and patriotism. And on November 8, 62 million people elected a proud bigot as Commander-in-Chief.

Think about the racial implications in sport and society. Sixty-two million citizens voted for Trump and intentionally or tacitly agreed with his campaign’s racist denouncements of black and brown people. Many of that constituency then filled massive stadiums and arenas across the country for three consecutive weekends and cheered for black and brown bodies in sporting contests.

These occurrences underscore the failure of integration, which has become a sham and a buzzword that amounts to a figurative pat on Uncle Sam’s back. Let me explain. What exactly does integration mean? In 1949, the Day Law was repealed and it overturned a 1908 Court of Appeals ruling that The University of Kentucky (UK) and all public schools in the state were prohibited from accepting African-American students. The repeal allowed Lyman T. Johnson to become the first black student admitted to the graduate school. UK Archives conclude that integration commenced in 1954 when 6 black students entered the 6,000 plus all-white student body.

That perspective was and remains typical, and reflects assumptive ideas on the praxis of integration. This rationale proposes that if persons of different racial backgrounds occupy the same spaces then the livelihood of the persons was equal. This could not be further from the truth. Although black undergraduates entered UK in 1954, their humanity was contested inside the university and they were denied access to opportunities available to their white peers. Black students could not live on campus, eat in the cafeteria or participate in co-curricular or extra-curricular activities enjoyed by their white brethren. Black students could not sit near white students—at best they could sit at the end of the first row, and as removed from white peers as physically possible. One history professor told Ann Roach, a black student, that he did not want her in class, and she should not raise her hand for participation. She was made invisible in this supposed academic space of racial inclusion. It was this frustration in part that inspired activism against what I term “discriminative integration.”

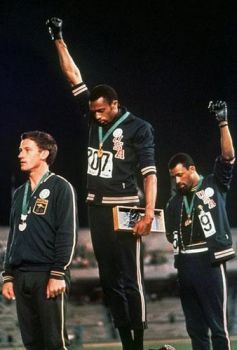

John Carlos (right)

The paradoxical arrangement of integration continued over time on college campuses across the country. In the early 1960s, East Texas State University framed itself as the most progressive school in the south. They were integrated and held an annual Old South Week extravaganza with white fraternity and sorority members in Confederate uniforms and dresses. One particular Kappa Alpha student was seated in blackface with slave written across his shirt. Meanwhile, Kappa Delta held a slave auction for its pledges. What did it integration mean for black and brown students on that campus? Ironically, this was the same institution that enrolled John Carlos in 1966-67—bronze medalist who with Tommie Smith rose their black fists at the awards ceremony in Mexico City at the 1968 Olympic Games. Carlos later transferred to San Jose State University.

None of these incidents are surprising and remain central due to the fragile definition and manifestation of American integration. Dean Cromwell, the “Maker of Champions,” legendary and hall-of-fame track and field guru that coached black athletes believed that their athletic success was due to an ancestral upbringing in the jungle. Exactly where was this mythical jungle that birthed these black athletes? He would be remembered as an integrationist while simultaneously viewing African Americans as uncivilized. It could be ascertained that in twentieth-century America, black athletes were seen by many as Ota Benga-like physical specimens even in integrated spaces. They were to be seen, examined and on some levels appreciated, and, at the same time, viewed as sub-human beings that lacked intellectual prowess or rights to American participatory democracy.

Over the years, many athletes, including Wisconsin basketball star Nigel Hayes and Florida defensive end Jonathan Bullard, spoke about this racial conundrum and double standard in sport and society. Scholars must provide pliable and nuanced interpretations of racism and integration to understand the complex politics of integration in American sport.

So what’s next for black athletes? Awareness and healing are useful but they fall short of bringing about change. Now is the time to call for pragmatic black nationalism, or the broad use of celebrity to engage social responsibility of black communities. Colin Kaepernick built on the recent and excellent work by Jason Brown, John Wall, Vince Carter, Jalen Rose, Dikembe Mutombo and others with his “Know Your Rights Camp” and million dollar pledge to organizations working in oppressed communities. We need more initiatives like these. I also believe we need to invest in historically black colleges and universities. As Martin Luther King Jr. asserted in his first major 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech at Cobo Hall in Detroit,

Gradualism is little more than escapism and do-nothingism, which ends up in stand-stillism… And in some communities we are still moving at horse-and-buggy pace toward the gaining of a hamburger and a cup of coffee at a lunch counter.

Those words embody the tragic livelihood of American integration. For black athletes, the fierce urgency of now requires vigorous and positive action in ways that empower their own communities.

Jamal Ratchford is an Assistant Professor at Colorado College and specializes in African-American history, 20th-century U.S. history, and Africana Studies. He is currently revising his book manuscript titled, “Raise Your Black Fists: Race, Track and Field, and Protest in the 20th Century.” He also has published an article, “The LeBron James Decision and Self-Determination in Post-Racial America,” in The Black Scholar.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.