Identity and Culture in Roman Africa: An Interview with Jennifer A. Rea

In his recent post “African American and the Classics: An Introduction,” David Withun highlighted the problem posed by the assumption of whiteness as a central element in the study of the Classics. Withun’s call to recognize the African American engagement with the Classics was illuminating. To stress the point, in September a controversy erupted around the criticism leveled by Rachel Fulton Brown, an associate professor at the University of Chicago, at Dorothy Kim, an Asian-American assistant professor of English at Vassar College, over Kim’s call for Medievalists to oppose supremacist groups’ misuse of the past. With these questions in mind, I noted the latest publication from Oxford University Press’ Graphic History Series: Perpetua’s Journey by Dr. Jennifer A. Rea and illustrated by Liz Clarke. The book joins a series of graphic novels based on primary sources used by scholars (For readers of this blog, previous books in the Graphic History series that explore West African slavery and the transatlantic slave trade will also be of interest). The series asks academics to build a graphic narrative that provides context and explores perspectives linked to these sources. Given the current debates about race and the classical past, I took the opportunity to contact Dr. Jennifer Rea about the graphic history based on the diary of a woman from Roman Africa. Dr. Rea’s research explores intersections around ancient Rome and modern science fiction and fantasy. She is the author of Legendary Rome, a work that explores three poets’ reinventions of Rome’s legendary foundation (the story of Romulus and Remus) in the context of post-civil war Augustan Rome. She is the recipient of the Ursula K. Le Guin Feminist Science Fiction Fellowship and an NEH stipend to attend a seminar on Roman Religion at the American Academy in Rome. Follow her on twitter @ProfJenRea.

Julian Chambliss: Who is Perpetua?

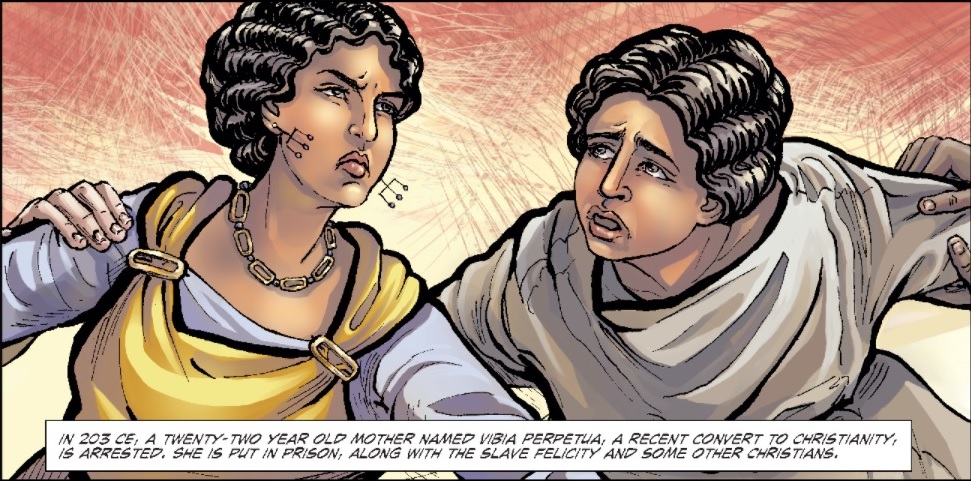

Jennifer A. Rea: Vibia Perpetua was a Christian martyr who lived in Roman Africa. She was arrested, imprisoned and then was martyred on March 7, 203 CE in the Roman amphitheater at Carthage along with several slaves and freedmen and a man named Saturus who was giving religious instruction to this group. She kept a diary about her experiences that led up to her martyrdom. Her account is the first extant diary we have from a Christian woman.

Her story resonates with us today because she relates her passionate struggle to fight for what she believes in but she also shows us the price she and her family pay for the choices she makes: she recounts her fights with her father, she describes how frightened she becomes when she is thrown in prison, and she details her longing for her baby when her father takes him away from her.

Chambliss: Africa is not the focal point of contemporary imagination when we think about Rome. What issues were there around questions of race and identity?

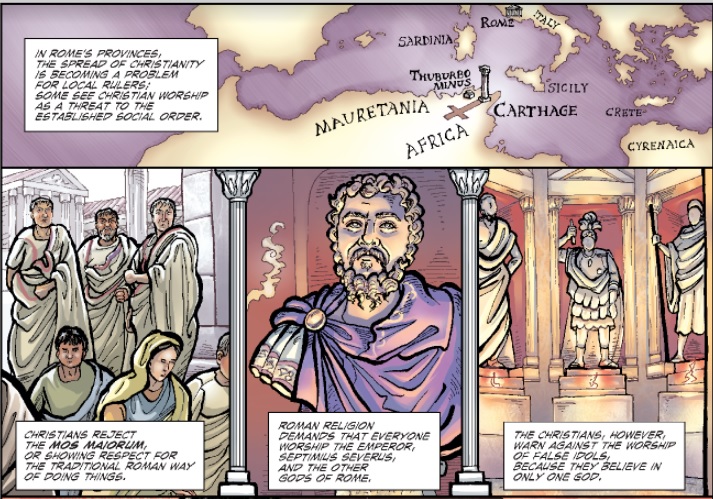

Rea: The events portrayed in Perpetua’s diary take place in 203 CE in Roman Africa. At that time, Carthage was a port city accustomed to a varied population coming in and out with trading ships. The city would have also had a diverse group of residents given its history with the Roman Empire. So while Rome also had a wide-ranging population, here is the first time in history that the Roman Empire has an African-born emperor, Septimius Severus, and he was popular in North Africa. In addition, many within the community in Carthage would have thought of themselves as having multiple identities. Perpetua was a Roman citizen, but also considered herself a Christian and a member of the community of Carthage in Roman Africa.

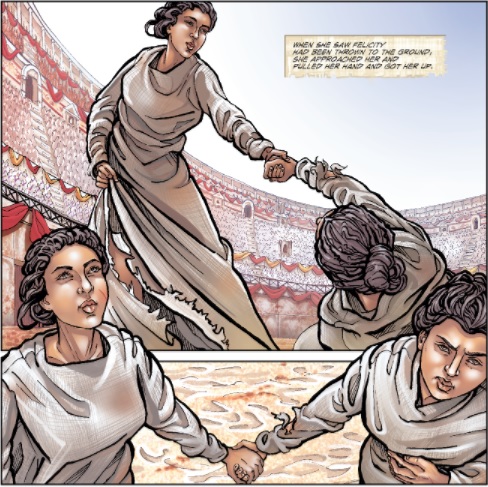

In part, her multiple identities are what make her diary so fascinating to read; she activates her Christian identity at key points to accomplish her goals, yet she is acutely aware of her status as a Roman citizen and how the Roman laws apply to her situation even though she is not residing in Rome. Perpetua is likely from a high strata of society, and she assumes the unofficial role of leader when confronted by Roman authorities. This also brings the question of gender into her story: at that time it was not legal for a woman to act as an advocate on behalf of others, yet she gains the respect of Roman officials because she argues so eloquently on behalf of herself and her fellow prisoners. So questions of race and identity in Roman Africa have to acknowledge the diversity of the population and how factors such as gender, status, etc., influence the construction of identity.

Chambliss: How has African identity been understood in contemporary classical studies?

Rea: I am going to give you a positive example from recent scholarship that demonstrates how important it is for classicists to think about how the ancients constructed identity: when examining the evidence, it is imperative not to assume something is “realistic” just because it makes sense to us in our modern culture. Dr. Mary Ann Eaverly’s book, Tan Men/Pale Women: Color and Gender in Ancient Greece and Egypt: A Comparative Approach, talks about color differentiation between men and women in art, and how to tell when it is symbolic versus naturalistic, and what this has to say about the political and cultural realities of the time in Egypt and in Greece. This kind of scholarship challenges conventional thinking about the relationship between race and skin color in antiquity and moves the discipline forward in a meaningful way.

Chambliss: How will your graphic novel deal with the question of intersectionality?

Rea: We approached the question by thinking of the intersection of various cultures in antiquity – including Roman and North African. One of the challenges that the artist, Liz Clarke, and I faced when trying to visualize Perpetua’s world and depict it in the sequential art was how to accurately portray her life in the 3rd century CE in Roman Africa when we did not have much information about her. She is also accompanied in the diary by a slave, Felicitas, and we are not given much information about her identity either. We could make educated guesses as to each character’s race and ethnicity, but in the end we could never really know for sure. So we decided to portray Perpetua and Felicitas as composite figures, and Liz drew from Greek, Roman/Italian, Arab, and Berber influences when designing their looks. In this way we acknowledged that we knew they were members of a multi-ethnic, racially diverse community.

We also had to consider how their world would have looked “Roman” – Roman colonies had all of the trappings of a Roman city, an amphitheater, forum, baths, etc., and show that the symbols of the emperor’s authority and reminders of imperial Rome existed everywhere. So these symbols of authority appear throughout the sequential art. But at the same time, this story was taking place in North Africa, so we had to consider how the physical and cultural environment would have affected the characters’ dress, living spaces, and other aspects of their daily lives. What would the landscape have looked like on their last walk from the prison to the amphitheater before their martyrdom? What would Roman soldiers’ dress have consisted of, given the climate? What kinds of material culture can you find in North Africa at that time?

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Wasn’t Felicitas Perpetua’s slave ? This fact seems to be glossed over in the interview where Jennifer A. Rea calls her only “a slave”. And it is not a minor fact: first of all, Perpetua seems to be portrayed as a very positive character in Dr. Rea’s book; and secondly, can we be sure that the martyrdom of Felicitas was consensual ?

Considering that Roman law didn’t demand for slaves to be executed along with their masters, or that owners couldn’t demand the execution of their slaves along with them, I’d say that the martyrdom of Felicitas was consensual.

Two other points that I’d like to comment on:

“Perpetua was a Roman citizen, but also considered herself a Christian and a member of the community of Carthage in Roman Africa.” I don’t undestand why this is even an issue worth pointing out. Multiple identities are the norm in most societies in history, more so in empires.

“So questions of race and identity in Roman Africa have to acknowledge the diversity of the population and how factors such as gender, status, etc., influence the construction of identity.”

“Liz drew from Greek, Roman/Italian, Arab, and Berber influences when designing their looks. In this way we acknowledged that we knew they were members of a multi-ethnic, racially diverse community.”

I’d like to give Mrs. Rhea a heads-up for any flack she is going to get by irate Italians, Greeks, or Arabs who will read into this some sort of racial discrimination/attempt by North Americans to reassign them into certain “races” that might exist in a North American framework, but not necessarily in Europe or North Africa.

Again. Discussion of a Christian

woman of Carthage North Africa

300 ad. which was not a world calendar

then or now, says very little about

“Roman Africa”. The Empire of Hannibal

might have cast more historical significance.