Howard Thurman’s Biographer: An Author Interview with Peter Eisenstadt

This post is part of our forum on Howard Thurman and the Civil Rights Movement.

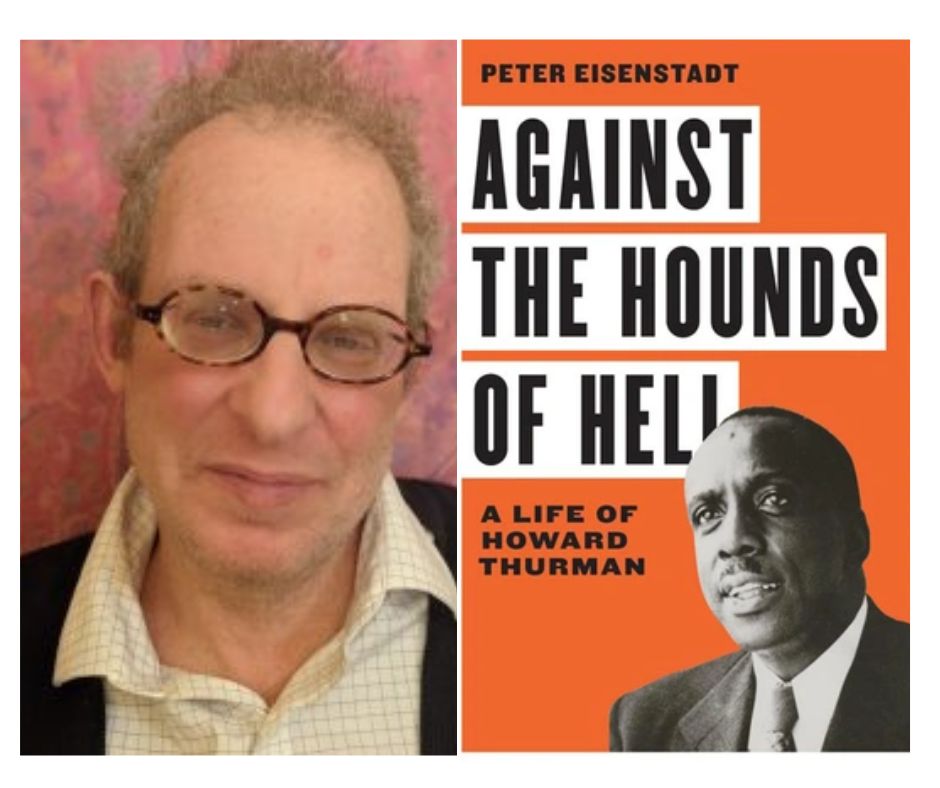

In today’s post, Tejai Beulah Howard, Ph.D., a senior editor of Black Perspectives, interviews Peter Eisenstadt on his work as a biographer of Howard Thurman. He is an independent scholar and an affiliate member of the Clemson University History Department. He is the author or editor of over twenty books, including the Encyclopedia of New York State, and Rochdale Village: Robert Moses, 6,000 Families, and New York City’s Great Experiment in Integrated Housing, which was awarded the New York Society Library Prize for the best book on New York City History. Against the Hounds of Hell: A Life of Howard Thurman, the first comprehensive biography of its subject, was the culmination of a long-standing scholarly interest. He was the associate editor for the five volumes of the Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, co-author with Quinton Dixie of Visions of a Better World: Howard Thurman’s Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence, and co-editor, with Walter Earl Fluker, of the four volumes of Walking with God: The Sermon Series of Howard Thurman. He lives in Clemson, South Carolina.

Tejai Beulah Howard (TBH): Studies on Pauli Murray and Bayard Rustin emphasize that their contributions to civil rights activism have been previously overlooked in the scholarship because of their sexual and gender identities. Why do you think someone as influential as Howard Thurman has been largely ignored as a subject outside theological studies?

Peter Eisenstad (PE): There are many partial explanations, none of them fully satisfactory. First, and probably most importantly, Black intellectuals have been systematically undervalued by white mainstream guardians of American intellectual life. Perhaps this has changed in the last few years, I am not sure, but it definitely was a factor during Thurman’s lifetime. I see Thurman and Reinhold Niebuhr, who, by the way, influenced one another in the 1930s as the two leading liberal Protestant religious thinkers in the middle decades of the twentieth century. But if the Niebuhr literature is a torrent, in comparison, the Thurman literature is a trickle. But this doesn’t explain why Thurman has often been undervalued or treated as an afterthought by students of Black intellectual life as well. Part of it is that, unlike your examples, Murray and Rustin, Thurman was not an “activist,” he was a largely retiring religious and social thinker who never sought the limelight or leadership roles. When his autobiography, With Head and Heart, was published in 1979, it received very negative reviews in both the New York Times and the liberal Nation magazine, both of which criticized him for his absence from civil rights activism, and both reviews completely misunderstood his crucial role as an inspiration to the movement. But he was content to preach, write, and counsel and was not interested and even uncomfortable with celebrity. And yes, the fact that he has been pigeonholed as a religious thinker has led to him being taken less seriously than he should be. I love theologians, but my work, as a historian, has been to try to place Thurman in the mainstream of Black intellectual life. His intellectual peers were not only folks like Benjamin Mays and Martin Luther King, Jr. but writers and thinkers like James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison as well.

TBH: You reference Thurman’s best-known work, Jesus and the Disinherited, in the title of your recent biography. Please explain to our readers who may be unfamiliar with Thurman’s text the significance of it to Black liberation theology and civil rights activism.

PE: Howard Thurman was the first significant African American pacifist. In early 1936, he and his wife, Sue Bailey Thurman, were half of the “Negro Delegation,” sent by American Christian groups on a “Pilgrimage of Friendship” to British South Asia. They were the first African Americans to meet with Mahatma Gandhi. Thurman was writing on pacifism as early as 1928. Jesus and the Disinherited, published in 1949, combines his commitment to radical nonviolence with his analysis of Black American life in the midcentury. Like all of his writing, it is lyrical and pastoral rather than sociological, and like all of his books, it is on the short side, little more than 100 pages. The first chapter is about what Thurman calls the “religion of Jesus,” which is the religion practiced by Jesus and not the worship of Jesus—Thurman did not think Jesus was divine. Jesus preached a religion as someone who did not have the benefit of Roman citizenship to other Galilean Jews who were non-citizens, or in Thurman’s terms, the disinherited. Citizenship and how, in its absence, the disinherited have no protection against arbitrary treatment, random violence, and death is key to the book and a key religious category for Thurman. The main chapters on fear, deception, and hate are the three “hounds of hell” that I refer to in the title of my biography. The chapters describe how the disinherited can overcome these blights through a combination of social action and spiritual strength, and the final chapter is an account of Thurman’s understanding of radical nonviolence. Martin Luther King, Jr. read the book within months of publication and quoted it, without attribution, in one of his student papers. It became one of the main texts of the civil rights movement. As one of Thurman’s most devoted students, Vincent Harding, once wrote, it is less a text of liberation theology than a “profound quest for a liberating spirituality,” and I think that is the best way to read it, though it has often been cited by those interested in liberation theology.

TBH: Thurman’s autobiography, With Head and Heart, describes his recollection of his father’s death and his maternal grandmother’s approach to reading the Bible. How did these events in his life and his academic training prepare him as a mystic and academic?

PE: Saul Solomon Thurman, Thurman’s stepfather, was not a believing Christian, and he died when Howard was around eight years old. He was preached into hell by the minister presiding over his funeral. This gave Thurman a lifelong skepticism and abhorrence of dogmatic religion. From his grandmother, Nancy Ambrose, and from others, a lonely boy discovered the strength of collective worship in the Black church. But he also was introduced by his grandmother into an Afro-Christian syncretic world of ghosts, “haunts,” and other apparitions. But Thurman was a spiritual genius who, whatever his early influences, independently discovered that God’s presence could be sought everywhere, in and out of the church.

TBH: W.E.B. Du Bois used the image of the veil to describe the problem of the color line in twentieth-century America. How did Thurman’s overall spiritual and intellectual project aim to break through “the veil”?

PE: Thurman knew Du Bois, and Du Bois asked Thurman in the 1930s to write an article on Black Religion for his abortive “Encyclopedia of the American Negro” project. There are many answers to this question; let me provide one. In the middle decades of the last century, one of the challenges of Black intellectuals was to explain Black oppression in ways that neither minimized or pathologized Black suffering. For me, Jesus and the Disinherited is an account of how oppression and racism can distort and curtail Black lives, but also how it can be an inspiration to all peoples who are disinherited, telling them that they can find the spiritual strength to overcome the forces that would demean and destroy them. Everyone, by inner reflection and spiritual self-discovery, can find their life’s purpose, their particular destiny, and thereby connect to the divine, and also connect on a deep level to others to bring about social transformation. It was a message that clearly drew from Thurman’s Christian heritage but was not limited to any specific faith tradition.

TBH: Thurman is often singled out as a critical influence on Martin Luther King, Jr. Beyond King’s reading of Jesus and the Disinherited and the brief time both men were in Boston, what does your research show about the extent of Thurman’s influence on King? What was Thurman’s influence on other well-known activists?

PE: I don’t want to sound cynical, but a connection to Martin Luther King, Jr. is the big prize in twentieth-century African American history, and if you can argue “x was a major influence on King,” which certainly is the case for Thurman, well, you take it, and everyone who has written on Thurman, including myself, has done so. But this has the consequence of reducing Thurman in some people’s eyes to a mere “forerunner,” important only insofar as he influenced King, and fosters the belief that all of Thurman is contained in King, which it is not. For one thing, Thurman’s critique of Christianity is considerably more radical than King’s. But there were others Thurman influenced more directly, such as James Farmer, his student at Howard University, and who, with the founding of CORE, became the first concerted effort to use the tactics of radical nonviolence against segregation, and Pauli Murray, who was close to the Thurmans at Howard and when they moved to San Francisco. Although Thurman was always a committed integrationist and at best skeptical of Black nationalism in the 1960s, he was a profound influence on a number of persons who were more sympathetic to nationalist politics, among them Jesse Jackson and the historians Lerone Bennett, Jr. and Vincent Harding. He was also very close to historian Nathan Huggins, the author of, among other books, Black Odyssey: The African American Ordeal in Slavery. And he was also a much-admired mentor to Derrick Bell, the legal theorist who has recently been lionized and demonized as the “founder” of Critical Race Theory. For all of these activists and thinkers, Thurman’s work helped explain the miracle of Black spiritual survival, despite slavery, Jim Crow, and the continuing struggle against white violence and white supremacy.

TBH: Thurman studies have been on the rise in the last decade. Why is work by and about Howard Thurman so urgently needed today?

PE: First, there is a much greater abundance of primary sources. If I can toot my own horn for a moment, I think the key development was the publication of the five-volume documentary edition, The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, edited by the Rev. Dr. Walter Earl Fluker, with myself and Dr. Quinton Dixie as the associate editors. And many other publications, including my biography, are shoots from that stock. And let me call out some other contemporary Thurman scholars, with apologies to anyone left out, the pioneering Thurman scholar Luther Smith, Paul Harvey, Amanda Brown, Gregory Ellison, among others.

Why is Thurman so urgently needed? Religion is too important a social glue and a source of individual identity to be left to the fanatics and the fascists. Howard Thurman was one of the pioneers of modern ideas of spirituality and of radical nonviolence as a political and spiritual way of life. And I would argue that there was a fundamental redefinition of the meaning of democracy, and the meaning of American democracy, by African Americans and African American intellectuals in the middle decades of the last century, and Thurman was at the core of that ferment—present at its creation. And this has yet to be fully recognized. I will admit to being somewhat biased, but I think Jesus and the Disinherited is a key text of American democratic thought, and if I had my way, it would be assigned in every class that reads the Federalist Papers and “Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address,” as well as in every AP African American Studies course.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.