Homicide Justified: The Legality of Killing Slaves in the Atlantic World

This is an excerpt from the preface of Andrew T. Fede’s Homicide Justified: The Legality of Killing Slaves in the United States and the Atlantic World, recently published by the University of Georgia Press. In the book, Fede offers a comparative study of laws concerning the murder of slaves by their masters and how these laws were implemented. Taking into account a wide range of cases—across time, place, and circumstance, in the United States but also in ancient Roman, Visigoth, Spanish, Portuguese, French, and British jurisdictions—his research reveals the changing legal reforms of slave homicide, and how these laws would underlay the legal attitudes of the Jim Crow era. This excerpt has been reprinted with the permission of the University of Georgia Press.

“Our community was deeply interested and excited yesterday, by a case of great importance and also of entire novelty in our jurisprudence,” reported the May 6, 1847 Charleston Courier. Eliza Rowand, a thirty-seven-year-old “lady of respectable family and the mother of a large family,” was tried for murdering Maria, a fifty-two-year-old enslaved woman. “The court-house was thronged with spectators of the exciting drama, who remained, with unabated interest and undiminished numbers,” until the jury’s verdict was announced. Although the Courier’s story included summaries of the trial testimony, Maria’s killer’s identity remains a mystery.

Charleston, the courtroom drama’s setting, was transformed between the 1670s and the 1730s “from a tiny provincial village to a rich and vital commercial center.” By the years between 1840 and 1860, the city’s population was almost forty thousand people. Charleston was unique among southern cities because between 1800 and 1850 slaves and free blacks outnumbered whites, and in 1820 and 1840 three-quarters of the heads of households owned slaves. Slaves were employed in various occupations, but most were household or domestic workers. The majority of slaves were women. Slave control was always a concern. Charleston in 1783 established the first urban police force in the United States. Fear of slave insurrection later increased, especially after the 1822 trials about the alleged Denmark Vesey rebellion.

Eliza or her husband, Robert, owned Maria, who was described as Eliza’s nurse. Eliza and Robert were married in 1833 and were the parents of five young children. Robert was a factor or broker in Charleston, where the family lived. A factor was the planters’ merchant and banker who bought and sold the planters’ crops and purchased goods for the planters.

On the day Maria was killed, January 6, 1847, Eliza called on E. W. North, her medical doctor, to come to the Charleston home of Eliza’s mother, Frances C. Bee. Dr. North stated at Eliza’s trial that he arrived at one in the afternoon and found Eliza downstairs in the sitting room “in a nervous and excited state,” which he said she had exhibited “for a month before.” North attended to Eliza. Although he contended that Eliza said nothing to him about Maria, North nevertheless went upstairs and found Maria’s body on the floor. He also noticed “a piece of pine-wood on a trunk or table in the room.” Maria was lying on one side, where he presumed she died. He noted some slight marks on Maria’s body and scratches about her face, but he did not examine her body before leaving the house.

The next day, Charleston’s district coroner, J. Porteous Deveaux, and a coroner’s jury held an inquest into Maria’s death. Before local police and prosecutors, homicide investigations and prosecutions began when a person notified the local coroner of a suspicious death. South Carolina law, like that in the other North American colonies and states, required coroners to assemble a coroner’s jury to examine the body and ascertain the facts. If the jury found evidence of a crime, the sheriff would arrest the suspect for a grand jury appearance.

The inquest began at Mrs. Bee’s home, where Maria’s body was found “in an out-building—a kitchen.” Deveaux said the body was “of an old and emaciated person, between fifty and sixty years of age.” The coroner’s jury then went to Charleston City Hall, where Eliza was examined. She gave a written statement asserting that early in the morning of January 6, 1847, she and Maria were at Mrs. Bee’s home. Her husband, Robert, was out of town. Eliza thought that Maria “misbehaved.” At about seven that morning, Eliza sent Maria to the Rowand’s home to be “corrected” by another slave named Simon. Maria returned to Mrs. Bee’s house about two hours later and went to Eliza’s chamber on the second floor, “where Maria fell down.” Eliza tried to revive Maria but was unsuccessful. Eliza then left the chamber. Another slave named Richard later came down to the first floor and said that Maria was dead. According to Eliza, no one struck Maria while she was in the second floor chamber. Maria died at about twelve o’clock.

Deveaux and the coroner’s jury next inspected the chamber in which Maria died. They observed wood pieces in the room and measured one piece, which was eighteen inches long, three inches wide, and one-half inch thick.

Two physicians examined Maria’s body at the coroner’s request. According to Dr. Peter Porcher, Maria was “lacerated with stripes; abrasions about the face and knuckles; skin knocked of[f].” He found evidence of blood under Maria’s scalp. He thought it likely she was hit one or more times on the top of her head and once just over the right ear and concluded that a heavy stick could have caused the damage. He found no other evidence of the cause of her death “except those blows.” Dr. A. P. Hayne gave a similar description of Maria’s body’s condition. He attributed her death to blows to the head by “a large and broad and blunt instrument.”

The coroner’s jury, after a more than ten-hour examination, found that “in the chamber of Mrs. Eliza Rowand, at the residence of Mrs. F. C. Bee, Maria came to her death in the forenoon of the 6th inst., by blows to her head, inflicted by Richard, the slave of Robert Rowand, by order of Mrs. Eliza Rowand.” The jury concluded that Richard and Eliza “feloniously did kill [Maria], against the peace and dignity of the . . . state aforesaid.” Eliza posted bail of ten thousand dollars on this charge.

Richard was first tried for Maria’s murder by a Magistrates and Freeholders Court, as South Carolina law required when slaves, some free Native Americans, and free blacks were accused of capital crimes. These defendants were denied the right to a grand jury review of the charges against them before their trials. They were instead tried quickly, not more than six days after their arrests, in an inferior court headed by one or two magistrates with a jury of between three and five freeholders.

Moreover, a slave’s testimony was inadmissible in trials against whites but not in the trials of other slaves. Therefore, Richard’s trial may have included the testimony of slaves who may have been present when Maria was killed.

Two magistrates presided over Richard’s January 1847 trial, and five freeholders composed his jury. Unfortunately, the newspapers followed the magistrates’ recommendation and did not publish even a summary of the testimony. Because Eliza’s murder charge was pending in the Court of General Sessions, the press thought “it incorrect to prejudice the public mind.” The magistrates charged the jury to acquit Richard if they thought that Eliza struck the fatal blows or if they found that Richard struck Maria at Eliza’s direction. The jurors “merely retired a sufficient time to write the verdict ‘Not Guilty,’ which was concurred by the presiding magistrates, and Richard was discharged.”

Three months passed before a Charleston district grand jury, on May 3, 1847, considered Eliza’s case. B. F. Hunt, representing Eliza, requested that the presiding judge, John B. O’Neall, charge the grand jury on the law of murder because “the case was a peculiar one.” Judge O’Neall, who was one of South Carolina’s most respected antebellum jurists, agreed. He charged the grand jury “that on an indictment for murder they should not find a Bill unless they were satisfied by the evidence that the deceased came under her death by the act of the accused—that the fact of the killing should be established by legal and not hearsay testimony.” The grand jury indicted Eliza on the murder charge, and a bench warrant was issued for Eliza’s arrest.

Eliza, on May 5, 1847, was arraigned in the Court of General Sessions. With her husband and mother by her side, she pleaded not guilty. The trial was held on the same day before Judge O’Neall and a twelve-man jury. Eliza was represented by a team of Charleston lawyers: James Lewis Petigru, one of Charleston’s most celebrated and respected lawyers; James S. Rhett; and B. F. Hunt. Attorney General Henry Bailey prosecuted the state’s case.

Judge O’Neall first granted Petigru’s motion to permit Eliza to sit by her lawyers rather than at the bar. O’Neall stated that “he granted the motion only because [Eliza] was a woman, but that no such privilege would have been extended by him to any man.”

Bailey opened his case by noting that an 1821 South Carolina law imposed the death penalty even on slave owners who were convicted of slave murder. Deveaux then testified about his coroner’s inquest, and Eliza’s exculpatory statement was read to the jury. South Carolina law had stated since 1740 that a slave owner, or one in control of a slave, was presumed guilty of murder if the slave died while under his or her command. But if no white person was present, the defendant could give an exculpatory statement under oath, and the state had to prove the offense by the testimony of two witnesses. Eliza’s written exculpatory statement thus came into evidence on the state’s own case in chief, and she could not be cross-examined about her story.

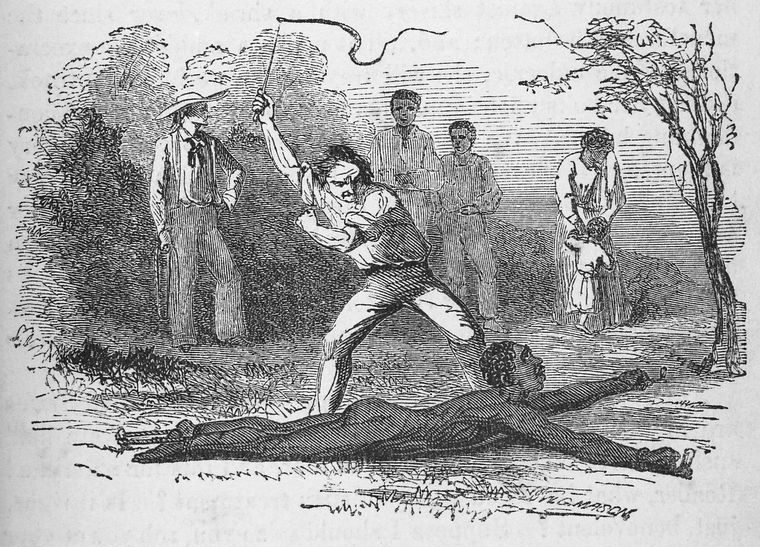

Hunt then made an opening statement on Eliza’s behalf. In the end he relied upon Eliza’s exculpatory statement and asked the jury to acquit Eliza because the state would offer only circumstantial evidence. Hunt also warned the jurors to consider only the testimony of “free white persons” presented under oath at trial. He expressed his trust that the jurors would not consider “unfounded accusations” or “legends of aggravated cruelty, founded on the evidence of negroes, and arising from weak and wicked falsehoods.” “Truth has been distorted in this case,” he stated, “and murder manufactured out of what is nothing more than ordinary domestic discipline.” Masters were entitled to chastise slaves to the extent necessary to ensure slave subordination, he argued, and masters—not their neighbors—should judge the limits of their own permissible slave punishment.

The defense team did not cross-examine Deveaux. The state offered no eyewitnesses to the crime. Dr. North testified of his visit to the scene of the crime and Drs. Porcher and Hayne testified about the condition of Maria’s body. They were cross-examined by the defense team, which offered no witnesses.

After the lawyers’ closing statements, Judge O’Neall instructed the jury that the state offered no proof that Eliza struck Maria or that she directed Richard to do so. He also referred to Eliza’s written exculpatory statement, noting “there was no sufficient evidence legally to contradict it.” O’Neall criticized the exculpatory oath statute but conceded that he was bound to apply this law. He recommended that the jury “acquit the prisoner, to whom the painful actions of the day might be a rebuke and warning of great value.” After twenty or thirty minutes the jury returned a not guilty verdict.

Life went on for Richard and Eliza after the trial. They had another child, and according to the 1850 census, they owned nine slaves. Robert died in 1857, and in 1860 Eliza still was living in Charleston with five of her children.

People in the South and North drew different conclusions from the case. According to the Charleston Courier, the trial demonstrated how South Carolina’s law extended to slaves’ lives “the aegis of protection, in the same manner as it does to that of the white man, save only in the character of the evidence necessary for conviction or defense.” In contrast, Harriet Beecher Stowe called the trial an indictment of southern justice, noting that “the case is reported with the utmost apparent innocence that there was anything about the trial that could reflect in the least on the character of the State for the utmost legal impartiality.” One of Stowe’s antebellum critics replied that Eliza “may have been guilty, but according to Mrs. Stowe’s own showing, there was no evidence against [Eliza], and a good deal for [her].”

Indeed, there was little admissible evidence against Eliza, in part because possible black or enslaved witnesses could not testify at Eliza’s trial. The rules of evidence and procedure made it relatively easy for Eliza’s dream team of lawyers to win her acquittal.

Thus, Maria’s killer’s identity remains unknown. It also is unclear how many other prosecutions were ditched as futile because enslaved people were not permitted to testify. Did the prevailing notions of “ordinary domestic discipline” permit slave masters to punish slaves by whacking them on their heads with planks? When did slave master homicide cross the line?

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.