History, Memory, and Gentrification

I spent my Sundays in November photographing in Clarksville—a neighborhood in Austin, Texas, which was founded by freedpeople after the Civil War. A colleague and Black Austinite, who has relatives from Clarksville, asked me to contribute photographs to her project on the “seen and unseen” of the neighborhood. Indeed, Clarksville no longer reads as a Black space. According to some of the remaining Black residents, there are only a handful of Black homeowners, and as of 2000, only 2.1 percent of the residents living within the boundaries identified as African American. The Black presence, while foundational, is no longer easily perceived. As an anthropologist, I welcomed photography as an ethnographic method to engage current and former Black residents and thus learn how and what to see in the neighborhood.

Established in 1871 by Charles (Griffin) Clark on the western edge of town, Clarksville now stands as one of the city’s most prized central neighborhoods. The tree-filled streets, mix of old and new homes, quaint restaurants, a coffee shop, and a local grocery store, lend themselves to a communal and upscale feel for those who can afford to reside there. With a median home value quoted at $557,400, plenty of million dollar homes, and being registered as a historic place, the neighborhood implicitly maintains a selective status with economics and race intricately and continuously at work. Boutique construction persists—old bungalows, sometimes the original wooden frame houses, are remodeled into larger homes with clean lines and a so-called modern appeal.

Gentrification is the language used to interpret this scene and the subsequent displacement that Black and other people of color experience. It is also a term encoded as a predominately white-driven affair. Within this frame, Clarksville exists in an advanced state of gentrification echoed in Austin and across the country.

Analyses of the historical roots of gentrification like the freedpeople’s communities in Austin exist, as do histories of Black resistance in Clarksville and the city in general. Affordable housing may be the city’s most vocal response to the matter. My photographic vantage, however, enabled me to rethink gentrification by connecting the ways memories and emotion, like the people who hold them, remain intertwined with the spaces of their pasts.

Black Presence

My colleague and I met each Sunday in front of Sweet Home, the founding church that survives at the center of the neighborhood. A signed letter from President Obama commemorating its presence hangs on the wooden paneled wall just inside the front doors. I had a chance to ring the original bell that now rests heavy as an anchor in the basement. I also viewed the original organ harbored in the back of the building. Across the way from the white church, I held and then photographed marbles, figurines, and rusted metal tools dug from the earth. We created a still life of old glass bottles and jugs atop the cistern from which they were pulled by its current white owner—an older man who has lived there for decades and appreciates the space, its findings, and history.

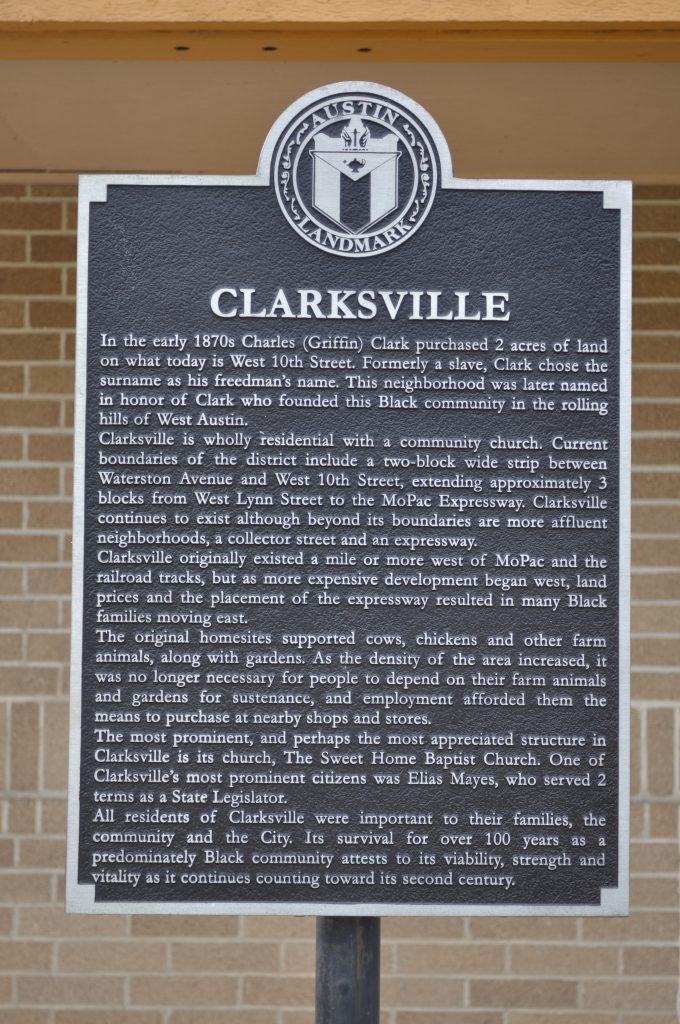

Other Sundays brought walks with folks, now in their 60s, who grew up in the neighborhood. One afternoon, two men who recalled playing as children, walked us up and down the original roads remembering them unpaved up until the 1970s. Through their voices, we heard the names, house by house, of the residents of their times. A park and a home-turned-community space now commemorate some of these residents as their namesakes—Mary Frances Baylor and Pauline Brown, respectively. On another day, we heard more about these beloved community leaders from two women in their Sunday’s best who grew up in the neighborhood. Standing near a historical marker about Clarksville at the local park, they recalled the small schoolhouse where a playground now stands in its place.

Memories of households and prominent residents also came with those of gardens, fruit trees, and grandfathers who kept hogs and maintained hen houses to sell or trade eggs. Our guides animated wooded areas through stories about the creek bed that crosscut and flooded the neighborhood. They described daily walks as adolescents to schools in a nearby white neighborhood separated by the railroad tracks. The vibrancy of life ways took precedence over racial lines in our conversations, even as they traced our footwork.

On the last visit, I walked with and photographed a former resident in his 60s. He remembered picking vegetables for one grandmother and bringing lunch to the other. One of these women taught him how to read and write. She guided him to use a ruler in one hand and a pen in the other to craft his cursive small and compact, making use of a full sheet of paper. He took me to a tree behind Sweet Home that he climbed as a kid and expressed that it might make a good backdrop for a photograph. As a lifelong congregant of the church, he said it had supported him through his many harder moments of life. He gestured to other trees on the church lot as well as to a fence where he gashed his eyebrow. Pointing to the scar, he recalled the conversation with his grandmother when he returned home covered in blood and the way she dressed the wound. Some minutes later, standing on a gravel-covered lot, he said it was his grandmother who spoke to him about the tenderness of his heart. This moved him to tears.

On the doorstep of one of the few preserved batten board homes, this same gentleman gestured to the wooden structure and rhetorically asked, “Is it history or memory?” He described the structure’s interior from visits to his “uncle” who lived in the home alone. He recalled listening to this elder’s stories of picking cotton, the songs sung in fields (which he sang for me), and his service in the US military. Memories of storytelling by the fireplace, which I could see through the window, brought the small historic home, for a moment, back to life.

Black Absence

Clarksville’s provenance now helps sell it. A 2017 commercial on-line profile of the neighborhood touts its origins as a freedpeople’s settlement, its historic status, and even references the 1928 City Master Plan that pressured and compressed Black people into East Austin. That Master Plan along with City construction in the neighbrohood contributed to the eventual buy-out of many Black people’s homes and displacement of Black residents. The article introduces Clarksville as, “ha[ving] the best of both worlds: It’s a quaint, quiet Austin neighborhood with unique homes, diverse residents and plenty of history” and it’s the neighborhood’s “historic nature” that has “protected [it] from the harried development happening elsewhere in Austin.” History here acts as a proxy for controlled building and the maintenance of the neighborhood’s charming character; however, it doesn’t speak of memory or reckon with the absence of Blackness.

When I returned home at night from my visits and sorted through photographs, the people and their memories felt alive. The social relations and networks that wove the neighborhood and organized my Sunday visits were generated primarily by Black people. More recent residents, almost certainly born elsewhere, may speak fluidly about the history but remember other neighborhoods, in other places. Claims to the strong neighborhood identity are purchased with homes and no longer cultivated through long-term residence or relationship with the space, the people, and ways of life that have been displaced. The historical narrative in its commodification has become a handmaiden to the neighborhood’s gentrification.

Memory unlocks a different way of understanding and deepening the conversation on gentrification. By moving from the appropriated historical narrative to one of memory brings into focus another constellation of concepts. Land can be reinterpreted as lineage; social relations can stand in the place of housing values; stories can grow credence like facts, and Black emotion can express Black displacement. Memory reveals how other histories are altered, built over, and erased through gentrification. The inclusion of memory highlights how racial and social processes influence perceptions of and relations to space and community whether of neighborhoods or cities.

As an anthropologist, who works with Black human archives, I value memory and its personal stories as central to the fabric of identity and community. I also recognize, as was the case in Clarksville, that storytelling, for some, was opening an old wound and risked additional neglect. There were some stories that were not for me to hear and others not for me to tell. Similar to my photographs, memories offer partial images and accounts and conceal others. My call is not to privilege memory over history, but to recognize how memory humanizes and complicates discussions of land and community. By locating neighborhoods and cities as human coordinates not just geographic and economic ones, memory asks harder, more relational questions about the places in which we dwell and grow our roots.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.